The World of Books

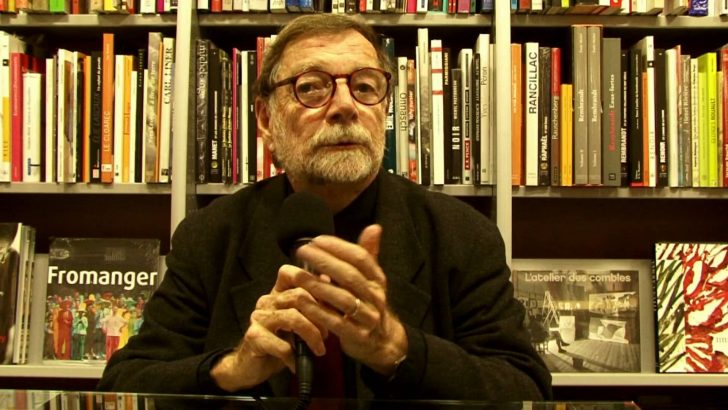

Si Newhouse died the other day, and as the American millionaire owner of some high-profile titles such as Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, he was something of a celebrity, a celebrity however with a dubious reputation. The name of André Schiffrin [pictured] may not be so familiar to many, but the New York firm which he ran for many years, Pantheon Books, was one of the most distinguished of its day. That is until it was taken over by Si Newhouse in one of the conglomerate building exercises that delight the executives, but in publishing at least, often cause dismay to the authors who get caught up in them.

The owners often act as if the authors were some sort of bond-slaves. Perhaps some are, but most aren’t: they can simply walk away. That is what happened at Pantheon. One of those who walked was a young cartoonist, promoted by Schiffrin, named Matt Groening, the creator of The Simpsons, an idea that developed into a high earning franchise that Si Newhouse was angry to have lost.

Si Newhouse’s new overall manager of his firms, a banker named Alberto Vitale, said Pantheon were losing too much money, about $3 million dollars a year – equivalent to the advance that Si Newhouse gave Nancy Regan for her memoirs, the sort of short term rubbish conglomerates delight it.

Schiffrin, on the other hand, had published Dr Zhivago and The Tin Drum, landmarks of literature, which remain in print, and make money for their publishers in a way that Mrs Regan’s now unread book never could.

Copyright

Long term, backlist publishing after all was the model of a firm like Macmillan in London, who published so many fine writers. For decades through the life of his copyright they reissued the books of Thomas Hardy, making more money over the 50 years involved than the celebrity books which sell for a few months and are often remaindered or pulped can do.

Good books make money, over time, whereas rubbish doesn’t. In the end quality prevails. But it needs time. The accountants who direct the great publishing conglomerates these days want their investment in a year or two.

One example of the new marketing notions is ‘World Book Day’. In the individual countries free books are offered, but to get them readers (often children) have to register.

Their details are then used, of course, for promotional activities, and not only of books. They become part of those sinister data banks we have no control over in which all kinds of details of our lives are, largely unknown to us, are accumulated and sold on. If the authors are bond-slaves already, their readers in turn will be enslaved to the needs of commerce.

‘World Book Day’ heavily promotes books by media celebrities. For 2018 these include Julian Clary, Nadiya Hussain, Clare Balding and Tom Fletcher, short term authors if ever there were.

Moreover, our Department of Education has agreed with the British agency running the ‘World Book Day’ to import and distribute in bulk the materials free to schools here.

But then this is modern publishing. It is not about culture, or merely promoting reading; it is about turning everything we do into a revenue stream for someone somewhere, to our disadvantage.

Developments

André Schiffrin describes and denounces these developments in his books The Business of Books: How International Conglomerates Took Over Publishing and Changed the Way We Read (Verso, $19.95), and Words and Money (Verso, $23.95).

The co-operative publishing model proposed for the future by André Schifrin, and attempted in the company he later founded, The New Press, is one that appeals to many writers. For the truth is that the most important and valuable books are not those which are ‘best-sellers’, but those which make themselves felt in the mind and imagination over time. Celebrity books rarely do this.

Strangely enough it is very much the way a great many Catholic publishers, and publishers with special philosophical or political interests, conduct themselves.

Perhaps far from being a last wave of the past, Catholic publishers and their kin may be the advance guard of a new future. Who knows? Certainly not the publishers.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Andre Schiffrin

Andre Schiffrin