Crimes of the Father by Thomas Keneally (Sceptre Books, £19.99)

Pauric Travers

Almost 50 years ago, schoolteacher and aspiring writer Thomas Keneally won his second Miles Franklin award for Three Cheers for the Paraclete, a novel set in the Irish-Australian Catholic community which explores the conflict between faith, obedience, freedom and authority.

Half a century and more than 30 books later, Keneally has returned to that setting and those themes in Crimes of the Father, but in a context which could hardly be more different.

In the meantime, Kennelly has established himself as a master story teller par excellence and the Catholic Church in Australia, as elsewhere, has been convulsed by scandal. The damage wreaked by sexual abuse on victims and clergy alike and on the standing of the Church is the focus of Keneally’s compelling new work.

Whereas the tone of Paraclete was light and humorous, that of Crimes of the Father is understandably dark.

Background

The historical background of this story will be broadly familiar to Irish readers and the immediate context will resonate even more so. In an author’s note, Keneally declares forthrightly: “I suppose you could call me a child of the Church. It defined me and gave my young life any higher meaning it possessed.”

The Church in which Keneally grew up was distinctly Irish, its mould having been set in the 19th Century by All Hallows and Maynooth and the influx of Irish religious orders who established and ran parishes, schools and hospitals.

While this began to change in the post war period with the influx of Catholics from other European countries, Irish Catholics remained a distinct group, socially, culturally, and even politically.

Keneally has earned a reputation for giving voice to the under-dog – Schindler’s Ark and The Chant of Jimmy Blacksmith spring to mind.

But the under-dogs that he chooses to give voice to are sometimes unexpected – as in Confederates, an American civil war novel from a southern perspective and Gossip from the Forest which presented an account of the armistice negotiations at Compiègne in November 1918 from a liberal German viewpoint.

Similarly Crimes of the Father gives voice to the struggles of the ‘good priest’. The trauma of the victims of clerical sex abuse is powerfully evoked but the main protagonist is the decent if flawed Fr Frank Docherty.

After years ministering in Canada, Fr Docherty returns to the Sydney archdiocese from which he had been exiled years before for his liberal views to speak at a conference on paedophilia. During the visit, he hopes to spend time with his elderly mother and smooth the way for a permanent return home.

Instead he gets caught up in a series of abuse cases involving an eminent cleric who is the brother of a close friend.

If Docherty pursues the truth as conscience and justice demand, the consequences may be devastating for many, including himself.

The novel is set in the 1990s at a critical juncture in the Church’s response to clerical abuse, not in the1970s when the horrific events which are described took place.

In an article on child abuse in the New Yorker around this time, Keneally, cited a priest friend who predicted that, if the Church failed to address the matter forthrightly, the civil authorities would be forced to do so with disastrous consequences for the Church and for all priests who would bear the opprobrium.

This is Fr Frank’s message to the Archdiocese of Sydney.

Crimes of the Father mourns the lives destroyed and the roads not taken. It also tries to exorcise some demons.

Docherty is a fictional character, but he owes something to priest friends of Keneally whom he admired, including one exiled in similar circumstances.

The novel owes something, too, to Keneally’s own journey from seminarian to ‘delicatessen Catholic’, a ‘cultural Catholic’ who, despite having rejected the institutional Church, retains a belief in the authenticity of Catholic spirituality.

Pauric Travers, first lay President of St Patrick’s College, is an historian with a special interest in Australia.

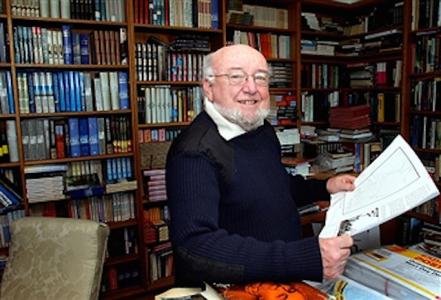

Thomas Keneally pictured at home

Thomas Keneally pictured at home