The excusable doesn’t need to be excused and the inexcusable cannot be excused. Michael Buckley wrote those words and they contain an important challenge. We’re forever trying to make excuses for things we need not make excuses for and are forever trying to excuse the inexcusable. Neither is necessary. Or helpful.

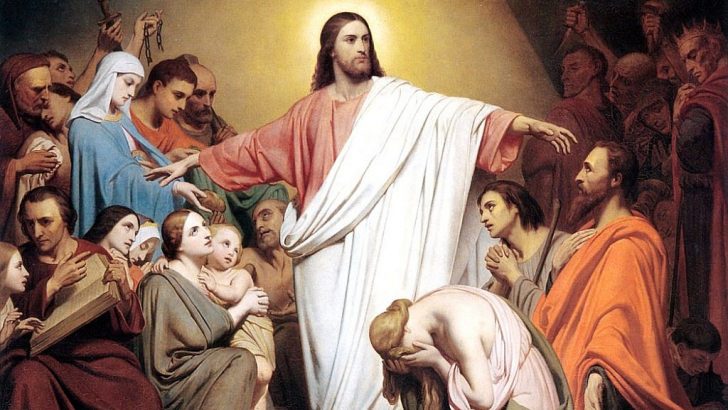

We can learn a lesson from how Jesus dealt with those who betrayed him. A prime example is the apostle Peter, specially chosen and named the very rock of the apostolic community.

Peter was an honest man with a childlike sincerity, a deep faith and he, more than most others, grasped the deeper meaning of who Jesus was and what his teaching meant. Indeed, it was he who in response to Jesus’ question (“Who do you say I am?”) replied: “You are the Christ, the son of the Living God.”

False conception

Yet minutes after that confession Jesus had to correct Peter’s false conception of what that meant and then rebuke him for trying to deflect him from his very mission. More seriously, it was Peter who, within hours of an arrogant boast that though all others would betray Jesus, he alone would remain faithful, betrayed Jesus three times, and this in Jesus’ most needy hour.

Later we are privy to the conversation Jesus has with Peter vis-à-vis those betrayals. What’s significant is that he doesn’t ask Peter to explain himself, doesn’t excuse Peter, and doesn’t say things like: “You weren’t really yourself! I can understand how anyone might be very frightened in that situation! I can empathise, I know what fear can do to you!” None of that. The excusable doesn’t need to be excused and the inexcusable cannot be excused. In Peter’s betrayal, as in our own betrayals, there’s invariably some of both, the excusable and the inexcusable.

So what does Jesus do with Peter? He doesn’t ask for an explanation, doesn’t ask for an apology, doesn’t tell Peter that it is okay, doesn’t offer excuses for Peter and doesn’t even tell Peter that he loves him. Instead he asks Peter: “Do you love me?”

Peter answers yes – and everything moves forward from there.

Everything moves forward from there. Everything can move forward following a confession of love, not least an honest confession of love in the wake of a betrayal. Apologies are necessary (because that’s taking ownership of the fault and the weakness so as to lift it completely off the soul of the one who was betrayed) but excuses are not helpful. If the action was not a betrayal, no excuse is necessary; if it was, no excuse absolves it.

An excuse or an attempt at one serves two purposes, neither of them good. First, it serves to rationalise and justify, none of which is helpful to the betrayed or the betrayer. Second, it weakens the apology and makes it less than clean and full, thus not lifting the betrayal completely off the soul of the one who has been betrayed; and, because of that, is not as helpful an expression of love as is a clear, honest acknowledgement of our betrayal and an apology which attempts no excuse for its weakness and betrayal.

We don’t move forward in relationship by telling either God or someone we have hurt: ‘You have to understand! In that situation, what else was I to do too? I didn’t mean to hurt you, I was just too weak to resist!’

What love asks of us when we are weak is an honest, non-rationalised, admission of our weakness along with a statement from the heart: “I love you!” Things can move forward from there. The past and our betrayal are not expunged, nor excused; but, in love, we can live beyond them. To expunge, excuse or rationalise is to not live in the truth; it is unfair to the one betrayed since he or she bears the consequences and scars.

Only love can move us beyond weakness and betrayal and this is an important principle not just for those instances in life when we betray and hurt a loved one, but for our understanding of life in general. We’re human, not divine, and as such are beset, congenitally, body and mind, with weaknesses and inadequacies of every sort.

None of us, as St. Paul graphically says in his Epistle to the Romans, ever quite measure up. The good we want to do, we end up not doing, and the evil we want to avoid, we habitually end up doing. Some of this, of course, is understandable, excusable, just as some of it is inexcusable, save for the fact that we’re humans and partially a mystery to ourselves. Either way, at the end of the day, no justification or excuses are asked for (or helpful).

We don’t move forward in relationship by telling either God or someone we have hurt: “You have to understand! In that situation, what else was I to do too? I didn’t mean to hurt you, I was just too weak to resist!” That’s neither helpful, nor called for.

Things move forward when we, without excuses, admit weakness, and apologise for betrayal. Like Peter when asked three times by Jesus: “Do you love me?” from our hearts we need to say: “You know everything, you know that I love you.”

Fr Ronald Rolheiser

Fr Ronald Rolheiser