Psychiatrist in the Chair: The Official Biography of Anthony Clare

by Brendan Kelly and Muiris Houston (Merrion Press, €22.95 / £19.99)

Charles Lysaght

Anthony Clare (1942-2007) attained, by the age of 40, an eminence in the medical profession in Britain not surpassed by any graduate of an Irish medical school since King George VI’s radiologist Peter Kerley and Terry Millin, the pioneer of prostate surgery.

A founder boy at Gonzaga and a graduate of UCD, Dr Clare was acclaimed for demystifying psychiatry in his book Psychiatry in Dissent (1976) and did important research on pre-menstrual tension. In 1981, he became a professor at St Bartholomew’s – a leading London teaching hospital.

❛❛Keen to put this country to rights, he joined in debates on abortion, divorce and other issues”

That was not enough for him. A champion student debater and inveterate controversialist, he craved audiences. As fluent on paper as in speech, he wrote articles for newspapers and magazines on a range of topics, many unrelated to his profession. Radio and television producers invited him on their programmes. He was counted as charming and amusing as he was hard-working.

His two roles came together when, in 1982, the BBC gave him a radio programme of his own entitled ‘In the Psychiatrist’s Chair’, a clever play upon words which gives this biography its title. He used the questioning skills he had honed as a doctor to explore the inner lives of those interviewed.

A succession of eminences subjected themselves to this. It was great listening. Interviews, such as those with comedian Spike Milligan, the eccentric politician Anne Widdecombe and cricketer Geoffrey Boycott (not mentioned in this book) were long remembered. The programme made Prof. Clare a national figure in Britain.

The wishes of Jane

In 1989, unable to resist the lure of the old sod, he acceded readily to the wishes of Jane, his wife of over 20 years and mother of his seven children, to return to their native Dublin. He became Professor of Psychiatry at Trinity and medical director at St Patrick’s Hospital.

Keen to put this country to rights, he joined in debates on abortion, divorce and other issues. But he was less acclaimed here than across the water. Critics panned a series of interviews of prominent Irish figures he did on RTÉ. He polled poorly when he ran in the National University of Ireland constituency for Seanad Éireann.

He kept up his BBC programmes, his Kent home and other London connections. But the resulting bilocation was exhausting and took its toll. His book On Men: Crisis in Masculinity (2000), treating the problems posed for men by the erosion of their former dominant role, had a mixed reception.

Crisis

By this time his own life was in crisis. He responded by resigning from St Patrick’s and abandoned, sometimes rather abruptly, his other activities, apart from the treatment of some private patients. To signal a new beginning he grew a beard, which did not suit him.

He lived between Dublin and Kerry with his wife, whom he described as his “rock”. They had met as UCD students. She was a sensible women who refused to believe herself devalued by devoting her life mainly to the support of her husband and care of her children. She was with him in a Paris hotel when he died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 2007.

This well-illustrated biography is written by Dr Clare’s successor as professor in Trinity in conjunction with a leading medical journalist. The thorough research undertaken is attested by detailed footnotes and a comprehensive list of Dr Clare’s writings. However, the treatment of psychiatry in the book is somewhat impenetrable for the lay reader.

❛❛He kept up his BBC programmes, his Kent home and other London connections”

The book captures his hyperactive, uneasy, combative personality and the ambition that Dr Clare attributed to maternal pressure. Otherwise it is skimpy on his relations with his parents, the deaths of whom are not even mentioned. His two sisters scarcely figure and only two of his seven children provided memories. Although he was not neglectful of his children, they seem to have suffered from his impatience and high expectations of them.

The authors skirt around what Dr Clare himself called “the near catastrophic event” that preceded his withdrawal into private life and led to feelings of guilt and failure that afflicted him in his final years. The assertion of a British colleague that he recovered the religious faith that he had lost in his prime is not corroborated.

If the book does not quite tell the full story and tends to the reverential, it is still a valuable record and a well-deserved tribute to a talented, courageous and versatile Irishman, who did more good than most, contributed valuably to public debate and provided entertainment that was illuminating, but who paid a price for the strain he imposed on himself in realising his ambitions.

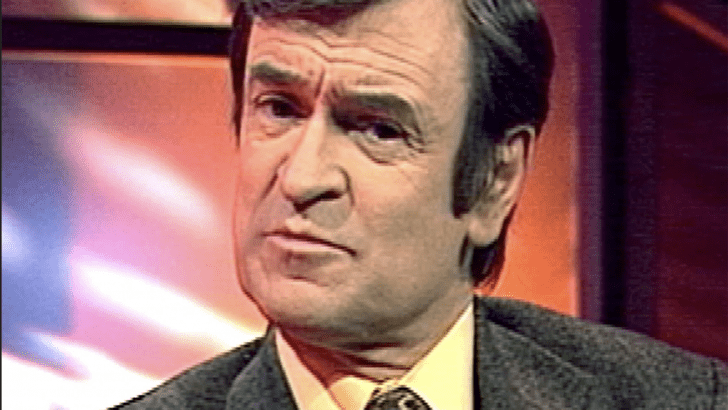

Dr Anthony Clare

Dr Anthony Clare