Ireland’s nuns have not been getting much respect of late, for reason that painful headlines make only too clear. But in all this controversy some things are lost sight of. Critics seem to think that the Church took over institutions that ought to have been run by the state; but the truth is that if they had not created these institutions the state would have done nothing.

Indeed education only became compulsory with the education acts of the 1870s, and even then, as many will know, children were able to leave school and start work at fourteen. We cannot bring to the past the expectations and attitudes of the present.

It also seems that many seem to think that the Church was flown in from somewhere else, almost from another planet. But the social attitudes of the Church, the nuns, and the priests, were those of the society that gave rise to them, the families that reared them.

If they are to be found wanting, it is because the Catholic people of previous centuries shared these attitudes. Our great grand-parents and their parents before them were to blame if cruel things were done in schools and institutions, because truth to tell Irish people as a whole did, quite casually, cruel things in those days.

We have to revise our ideas perhaps and recognise all the good things that were in fact achieved. Here is a book published in advance of the tercentenary of the birth of the great educator Nano Nagle 1718, which will prove enlightening, not just to Catholics, but everyone in Ireland.

Nano Nagle is one of the great heroes of social justice in Ireland. She was declared venerable by the Pope in 2013, which might have been expected. More surprising is that the listeners of Marian Finucan’s radio show two months ago voted Nano Nagle, who died in 1784, “Ireland’s greatest woman”.

This book is not, as is so often the case with centenary publications, a biographical book, but a series of contributions on ideas and attitudes, motives and aspirations arising from her work. While all the contributors have the past closely in mind, their focus is also on the future, on the essential continuity in the developing Presentation sense of mission.

The preface by Prof. Thomas O’Loughlin, the President of the Catholic Theological Association of Great Britain, remarks that “the first premise of all history is that the present is always different from the past, and so the future will be different again: tomorrow will be another day. And for Christians this is simply not optimism: it is the hope that fullness of life lies in the future rather than the past.”

This heartening notion is well illustrated in the essays here, suggesting that the vocation of Nano Nagle is far from exhausted. It has many new fields of work.

Peter Costello

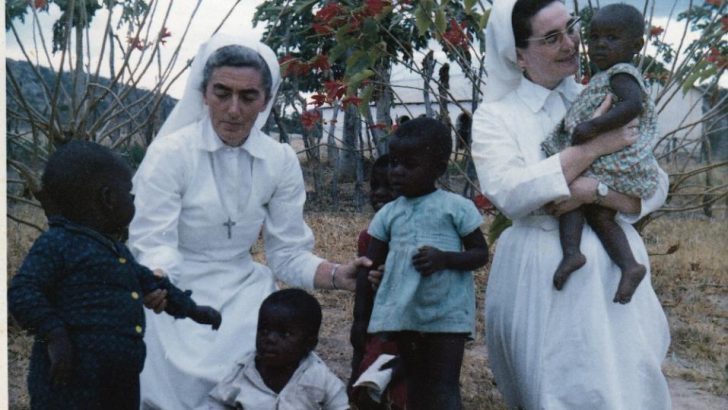

Peter Costello Presentation nuns at work today in Africa.

Presentation nuns at work today in Africa.