By trying to over-psychologise everyday life we do people a huge disservice, Prof. Patricia Casey tells Michael Kelly

Over decades of professional practice and a ready willingness to appear in the media, few people have contributed to the public understanding of psychiatry as much as Prof. Patricia Casey.

And yet, the realm of mental illness remains one that can be as difficult to talk about as ever. Covid-19 restrictions have not helped. The constant policy of on/off lockdowns and disruption to daily life has contributed to greater anxiety by any measure and those who are in urgent need of psychiatric help to deal with their mental health issues face the prospect of further delays.

“The waiting list has only grown over time and the current infrastructure is not adequate to provide the right kind of help to those who need it,” Prof. Casey told The Irish Catholic.

She has just published her latest book which she hopes may provide some much-needed relief for those struggling with mental health, whether for themselves or those around them.

Fears, Phobias and Fantasies – Understanding mental health and mental illness is a first-of-its-kind guidebook aimed at laypeople, not academics or experts in the field. While Prof. Casey’s contribution to the academic field is vast, this new book seeks to redress a growing gap where people wish to research and understand what they or family members and friends are going through without having to resort to some questionable material being offered online.

Warn

Prof. Casey is keen to warn about the perils of some of the unscientific advice offered online to people who are mentally-ill. She underlines the centrality to psychiatry of using “scientific approaches and applying these to the study of mental illness in the same way that they are to physical illnesses”.

With actual case vignettes, succinctly put diagnoses and treatment suggestions, as well as a step-by-step guide for how to go about seeking help and what exactly it entails, Fears, Phobias and Fantasies will be an invaluable tool.

While people have been talking about mental health problems from the time of Aristotle, psychiatry itself is a relatively modern discipline. The word psychiatry did not come in to common usage until the early 1900s. Earlier approaches were rudimentary and treatments often rare.

“There were no medicines available to treat depression or to treat panic disorder in the way that there are now. So – on the one hand – in the early days you had extreme institutionalism going hand-in-hand with the psychodynamic approach: people talking about their childhoods, their fantasies, their dreams, etc.,” Prof. Casey says adding that both of these aspects have changed “immeasurably in the last century”.

Shift

One of the big obvious shifts is away from the large psychiatric hospitals that were once a feature of the outskirts or every provincial town. Most people now requiring inpatient psychiatric care receive this in a local hospital while people with milder conditions get a combination of psychological therapies and medication.

But, isn’t medication controversial I ask? “Some people might say people with the milder conditions get too much medication, and there is an element of truth in that certainly. But medication when it is used appropriately is very good – it’s an excellent treatment,” Prof. Casey insists.

Over her professional career, she has become increasingly concerned about what she describes as people being over-psychologised and “referred for psychological interventions when they really don’t have any kind of mental health problem that needs a professional to help them, but time and friendship and support would be sufficient.

“Psychiatry has always been bedevilled by extremes in my opinion,” she says.

There is no question that if mental health was a taboo in the past, people have become much more comfortable talking about it. Nowhere is this more obvious than looking at tabloid newspapers. Each day there are stories about x or y celebrity ‘opening up’ about their mental health or ‘revealing’ their struggles.

High profile

High-profile cases of people who have taken their own lives after having appeared on popular television programmes such as Love Island have also increased the focus on mental health in the media.

Undoubtedly, Prof. Casey says it is important to talk about mental health in the media but, “it’s a double-edged sword…It’s a good thing that people are more comfortable talking about depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, etc.

“There is still some reticence about it, but it’s good that people can be open about it and feel comfortable coming to see a psychiatrist without feeling overly stigmatised,” the professor says.

But, back to the double-edged sword: “As against that there is a danger that people will open up ‘willy-nilly’ to everybody who’s willing to listen about their inter-personal problems…often mental health difficulties have their origins in childhood trauma, not always, but often they do. And that kind of confessional approach and that kind of ‘tell all’ approach isn’t helpful either to people themselves or to the public,” she insists.

This brings the conversation naturally to a certain California-based couple who have been playing out a very public rupture with the British Royal Family over recent years. “I have to say, I think Prince Harry has contributed very negatively to all of this in that people are talking about normal distress as though normal distress is a mental health problem,” Prof. Casey says.

Distress

“Normal distress is a sign of health. If you didn’t have distress in some situations, you would probably either be dead or be a psychopath. It’s very important that people are distressed in certain situations when they’re bereaved, when they have difficulties with their parents, etc and it’s very important that they feel sad…It’s very important that people feel anxious before exams, for example,” she adds.

Prof. Casey also warns against a modern tendency to see mental health problems as ubiquitous. “Take Covid-19, it has had a huge effect on people’s level of distress – but most people are not mentally-ill because of Covid-19…they’re fed up with it, they’re anxious and worried in case they get it, they’re anxious in case their loved ones get it but they’re not mentally ill.

“I think it is undermining the reality of mental illness for those who genuinely have it to talk about distress and worry in the same breath,” she says.

Prof. Casey and her family have had their own experience of grief. She and John adopted Gavan and James when they were very young.

Gavan, who had already recovered from cancer of the nose when he was just five years old, was diagnosed with a tumour of the spine two days after his 24th birthday. He died five months later.

Grieving

While she was grieving for Gavan, she was struck by the number of people who suggested therapy for what was a perfectly normal reaction.

Prof. Casey recalls “people telling me ‘You must go for counselling’ even while he was ill. ‘You must go for counselling’ – never mind the fact that I worked at a department of psychiatry with a wonderful colleague who was immensely supportive to me and a husband here at home, and another son who were immensely supportive, and very many friends who were supportive.

“But yet people wanted to send me ‘to do something about it’ – and there is nothing to be done about understandable sadness, it’s part of the veil of tears that we live in,” she says.

On a personal level, Gavan’s original illness as a child had tested Patricia’s faith. When the cancer returned, she said she found it “immensely helpful” for her spiritually when he received the Sacrament of the Sick as he neared the end of his life.

Speaking of the cancer that would eventually take his life, she says “surprisingly it didn’t test my faith. When Gavan was ill the first time around it tested it much more, I can’t explain it because I anticipated that it would,” Prof. Casey said.

She recalled how she had been at the Edinburgh festival with her family when Gavan developed a limp and returned to Dublin as it became more painful. She received a call with the news of his diagnosis.

“I sat outside the shop [in Edinburgh] and I must have looked very pale because – I’ll always remember this – a young man walking along with a bottle of water and a burger in his hand, said: ‘Are you alright?’ and I said ‘no I’m not, I’ve just heard my son has cancer’ and he said ‘I’ll call a cab for you’.

“And he did and then he said to me: ‘God bless you, I’ll pray for you’, and he walked away, I’ll always remember that,” she said, “it was very kind.”

I ask if Prof. Casey sees the modern aversion to grief as part of the same tendency to psychologise everything.

“Yes,” is her immediate reply. “Unfortunately, there is an industry out there – a psychotherapy industry. And I don’t say they do it in any malevolent way, they want to make life easier for people. But it really doesn’t. And for many people, it disturbs their grief and their sadness if these normal processes are interfered with too vigorously or too early.

“Counselling does have a role in some cases, of course it does. I don’t want your readers to think that I’m opposed to it – but I think we have to be very judicious in the situations and circumstances in which we do use both medication and talking therapy,” she insists.

Rationale

This is part of the rationale behind the new book – helping people discern what is best in a given situation.

“I am a practicing psychiatrist, and when patients come to see me about themselves – or maybe with a loved one – they want information about the condition that I diagnose (if I do diagnose a condition).

“There is a lot of information out there in the public domain, some of which is patently inaccurate and some of which is most helpful. So, I thought I would try and put it into a single book for all of the conditions for the Irish public,” she says.

It’s a difficult question: how do we know if someone has a psychiatric illness, or how do we know if what they’re experiencing is normal distress? “I cover that quite extensively in the book, because that’s quite a difficult concept to get across in a talk or in an interview. My book is peppered with explanations as to how one identifies what we call psychopathology and normal variation in symptoms,” she says.

The book is as user-friendly as it is accessible – Prof. Casey was adamant that it must be a book that would appeal to non-professionals. “Making it a handbook for your average person was exactly what I intended,” she says.

Tool

As well as someone concerned about themselves, she hopes that it will be a valuable tool for people who might be concerned about a loved one or a work colleague.

As we speak, research has just been published by a British university indicating that 60% of young adults say they feel anxious either all of the time or most of the time about the issue of climate change. The issue is due to be discussed by world leaders in Scotland next week and is rarely out of the headlines. The troubling British research makes me wonder if this generation is more anxious than those who have gone before. Some newspapers have even spoken of an ‘epidemic of anxiety’.

“In my opinion, there is no epidemic of anxiety,” Prof. Casey says. Referring to the research I cite, she points out that it was actually a telephone interview. “Telephone interviews always tend to get highly positive scores for what we call ‘false positives’. People who self-rate themselves tend to score more highly and more positively because there isn’t any nuance to the questions.

“And when you’re on the telephone doing – maybe a 20-minute interview – people don’t sit and have time to deliberate: ‘am I really like this all of the time?’ They may only think about the past 24 hours, or the past two days or whatever.

“Also, when something is in the news, people’s anxiety is going to be heightened – perhaps unnecessarily, perhaps necessarily who knows,” Prof. Casey says.

On heightened anxiety about a rise in Covid-19 cases on the island of Ireland, Prof. Casey says that people will ultimately have to learn to live with the virus rather than feeling constantly preoccupied about it.

Preoccupation

“There is a lot more worry and a lot more preoccupation about getting it [Covid-19]. But I think it will ease, and when people get back into more normal type work – perhaps a hybrid type work working from home and the office – things will settle and when people can start socialising again the stress will get less.

“And in time, hopefully as we get herd immunity, people will learn to live with Covid in the same way that we learn to live with many infections that at the beginning were potentially very serious.

“Even the ordinary flu can be life threatening, but yet people learn to live with it…I think that’s what will happen,” she says.

One theme that Prof. Casey returned to again and again in the book is that of resilience. She believes that the starting point is people knowing that unpleasant emotions are a normal part of life. “Don’t be frightened if you have a ‘bad hair day’, or if they’re crying for a few days after they split up with their boyfriend or their best friend.

“I’m very concerned that in the UK at the moment, there are now classes on mental health in the secondary schools. And I don’t think that that is terribly helpful. I think it’s going to heighten young people’s worry and self-analysis in young people who are already very inwardly-focused and I think this will make it more so.

“I would not be rushing in to have mental health classes in secondary schools,” she says adamantly.

Fears, Phobias and Fantasies by Prof. Patricia Casey is published by Currach Books and is available on their website as well as in all good bookshops.

Michael Kelly

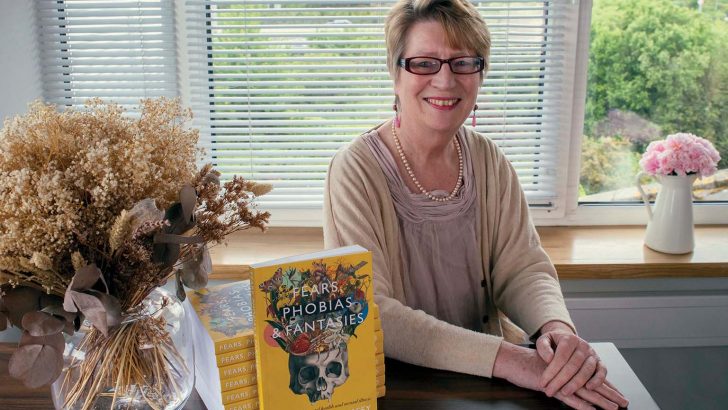

Michael Kelly Prof. Patricia Casey with her latest book Fears, Phobias and Fantasies by Currach Books. Photo: Alexis Sierra

Prof. Patricia Casey with her latest book Fears, Phobias and Fantasies by Currach Books. Photo: Alexis Sierra