St John Henry Newman knew that the Catholic Church was the Church of the earliest Christians, writes Mike Aquilina

At the heart of St John Henry Newman’s conversion from Anglicanism to Catholicism was his study of the early Christians, the fathers of the Church.

As an Anglican clergyman, he believed that they held the answer to his denomination’s perennial problem – fragmentation in doctrinal and practical matters. He sought a purer reflection upon Scripture in the writings of the fathers, an interpretation untainted by modern politics and controversies.

Yet his methods were – and remain – particularly appealing to modern readers. I confess I’ve filched them shamelessly as I prepared my books, especially Roots of the Faith.

Newman, whose feast day the Church celebrates October 9, read the fathers deeply, and not merely to extract theoretical propositions. He wanted to enter their world – to “see” divine worship as they saw it, to experience the prayers as they prayed them, to insert himself into the drama of the ancient arguments.

He immersed himself in the works of the fathers so that he could recount their stories in his brief Historical Sketches, in his book-length studies and, later, in one of his novels. After decades of such labours, he concluded that “of all existing systems, the present communion of Rome is the nearest approximation in fact to the Church of the Fathers. … Did St Athanasius or St Ambrose come suddenly to life, it cannot be doubted what communion he would take to be his own”.

An interesting thing had happened. Newman’s study of the fathers of the Church had caused him to desire The Church of the Fathers (yet another of his book titles). He wanted to place himself in real communion with the ancients, with Athanasius and Ambrose. A notional or theoretical connection wasn’t enough, and could never be. He wanted to move out of the shadows of hypothetical Churches, based on a selective reading of the Church fathers, and into the reality of the fathers’ Church.

In declaring Cardinal Newman a saint in 2019, Pope Francis has held up his life as worthy of imitation. And, in the matter of encountering the fathers, it should hardly be a burden.

Like Newman and his contemporaries, so many people today hold a lively curiosity about Christian origins. Many ordinary Christians would like to move beyond the rather petty preoccupations of today’s tenure-track historians and documentarians (gender and conflict, conflict and gender). They would like to find their own imaginative entry into the world of the Church fathers. They would like Historical Sketches that were vivid enough to see with an attentive mind’s eye.

And what would we see in the works of the fathers? What would we see as we gazed through the window provided by archaeology of early Christian sites? We would see many familiar sights and sounds, fragrances and gestures:

– A Church gathered around the Eucharist. This emerges most vividly, not only in the Scriptures, but in the generation immediately after that of the apostles, the generation of the so-called apostolic fathers. The document called The Didache (circa AD 48) includes the earliest Eucharistic prayers. Clement of Rome (circa AD 67) sets out the different roles of clergy and laity as they come together for Mass. Ignatius of Antioch (circa AD 107) describes the Eucharist as “the flesh of Christ” and treats the Sacrament as the principle of the Church’s unity. By the time we get to Justin Martyr (circa AD 155), we find a full description of the Roman Mass that’s recognisable enough to be reproduced verbatim in the Church’s catechism today.

– A Church that practices sacramental Confession. The fathers argued amongst themselves about whether the Church should be strict or lenient in dispensing penance – but none of them denied that this was the right and role of the Church and her clergy. The fathers heard confessions. They pronounced absolution.

– A Church whose members make the sign of the cross. At the end of the second century, Tertullian spoke of the sign as if it were the hallmark of ordinary, everyday Christian living. Among his wife’s beautiful qualities he mentioned the way she made the sign of the cross at night.

– A Church whose members bless themselves with holy water. The “prayer book” of St Serapion of Egypt (fourth century) includes a blessing for holy water. Eusebius (late third century) describes the familiar font at the entrance to a church.

– A Church with an established, sacramental hierarchy. St Ignatius of Antioch shows us that, as the first century turned over to the second, the order of the Church was already well established everywhere. As he wrote letters to various churches, he assumed that each church was governed by bishops, presbyters and deacons. He didn’t explain this. He didn’t argue for it. He just assumed it. At the turn of the next century, Clement of Alexandria also presented this order as traditional – an imitation of the hierarchy of angels in heaven.

– A Church that venerates the saints. This shows up in the graffiti on the walls of the Roman catacombs. It shows up in the art of the cemeteries of the Fayoum in Egypt. It shows up in many lamps and medals and signet rings. St John Chrysostom and St Augustine wrote numerous homilies on the lives of the saints. The most ancient liturgies invoke their intercession. This is especially true of the Virgin Mary, whose prayers are included in canonical collections by the early third century.

– A Church that prays for the dead. In the 100s, devotional literature describes votive Masses celebrated at gravesides. The earliest tombstones in Christian Rome ask prayers for the deceased. The prison diary of St Perpetua (North Africa, early third century) includes a vision of purgatory – whose existence is explained theologically by Origen (Egypt, third century). At the end of the 100s, Tertullian describes prayer for the dead as already an ancient practice.

– A Church with a distinctive sexual ethic and clear ideas about marriage and family. The early Christians stood almost alone in their refusal to acknowledge divorce, to engage in homosexual activity, to procure or practice abortion or to use contraception. Their view of sex as sacred made them a laughingstock in the pagan world, where sex was cheap and degrading, and people were, accordingly, miserable.

That’s just a glimpse of the early Church, but it’s enough to make it recognisable as Catholic. Nor did the fathers see their life as in any way opposed to Scripture. Scripture and tradition coexisted in harmony because they had been received from the same apostles. The New Testament shows us the apostles writing letters, yes, but also observing rites, customs and disciplines.

Moreover, the Church of the apostles pre-existed the New Testament and shows us that authority, for Christians, does not rest simply in the Scriptures.

“First of all you must understand this, that no prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation” (2 Pt 1:20). For the fathers, interpretation belonged to the Church and her bishops. St Polycarp of Smyrna took that lesson well from his master, the Apostle John. In the middle of the second century, he wrote: “Whoever distorts the oracles of the Lord according to his own perverse inclinations … is the first-born of Satan.” Polycarp’s great disciple and doctor of the Church, St Irenaeus of Lyons, made that one of the foundational principles of his multivolume work, Against the Heresies.

St John Henry Newman knew that, standing apart from the Catholic Church, he was standing not with the Church of the fathers, but rather with the heretics. So he came home, and his way – the way of the fathers – has been traversed by many non-Catholics since then.

Mike Aquilina is executive vice-president of the St Paul Centre for Biblical Theology and the author of more than seventy books.

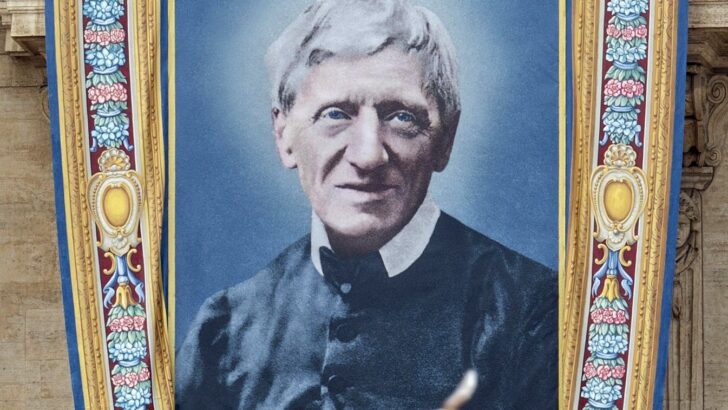

A banner of St John Henry Newman hangs on the facade of St Peter's Basilica at the Vatican.

A banner of St John Henry Newman hangs on the facade of St Peter's Basilica at the Vatican.