We are now at the stage of the pandemic where the gurus are emerging to bestow advice about depression and the toll that lockdown is taking on our mental health.

A variety of nostrums are being offered to help deal with the stress of continuous lockdown – with little hope of eased restrictions this side of Easter.

Immunologists are warning that while acute stress – the tension that spurs you to win the egg-and-spoon race at school sports’ day – can boost your immune system, chronic or ongoing stress can make you more liable to illness. Infections invade the body whose resistance is lowered by chronic stress or depression.

Advice proffered includes getting out into green spaces – although that might be penalised by the authorities if you wander too far from base.

Don’t eat for comfort – oops! Oh dear. I’ve been scoffing the chocolate for a while now, and it shows.

Limit your screen time – but what if the screen is your only contact with what’s laughingly called ‘the outside world’?

A boffin at the University of Portsmouth, Mike Tipton, suggests taking a regular dip in icy water. Yes, I must try wild-water swimming. But, as St Augustine so suggested, perhaps not quite yet!

Avoid caffeine in the afternoon. What? But a real cup of tea in the afternoon keeps me sane!

If depressed by Covid-19 restrictions, keep a journal. I already do that, and it reads like the memoir of a misery-guts.

Marian Keyes, bestselling author who has written about her own tussles with depression and alcohol, advises that you murmur to yourself, repeatedly, ‘This too will pass’. When a day seems unbearable, break it down into manageable chunks – an hour at a time, say.

But ‘this too will pass’ – though advice from the wisdom of the ages and of many holy people – has a downside, Marian. ‘It’ will pass – but so will we. For older people, there’s an acute awareness that any of us could ‘pass away’, in the current euphemism for dying, before the pandemic passes us by. Some people may be ready for this: others may be plunged into a sense of foreboding grief.

A Stoic website advises: “commit to the hard path”. Those ancient Athenians just told people to get resilient and accept that life is tough

Everyone has their own way of dealing with the lockdown melancholy of isolation and confinement. My own method is to pretend that I’m on an extended retreat – a year-long withdrawal into the desert. This time is given to me, I tell myself, to experience life in a different way: to contemplate my past errors and future endeavours of amendment.

That gets me through, just so long as I can have the teeniest, weeniest piece of chocolate!

A brilliant writer with unusual origins

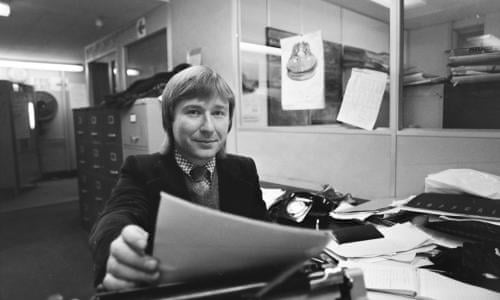

The current focus on adoptive children having the right to trace their birth parents has put me in mind of the late journalist David Leitch, who was a good friend of my husband, Richard West. David later became my friend too.

Mr Leitch was a brilliant writer, mainly associated with The Sunday Times, covering a number of terrifying conflicts in Vietnam, the Middle East, and Cyprus, and later becoming a specialist in espionage, co-authoring the first major book about Kim Philby.

His early life had been extraordinary: at eight days old, he had been sold by his birth parents, who put an advert in The Daily Express about a baby for sale. A suburban couple from Harrow answered the advert and baby David was duly handed over to his adoptive parents at the Russell Hotel, near the British Museum in London’s Bloomsbury.

His adoptive parents were dutiful, if a little narrow: they sent him to a top-class school and he sailed through Cambridge University with flying colours. His talent then brought him early success.

In 1973, he wrote a book about his birth circumstances, God Stand Up for Bastards (a quote from Shakespeare) which revealed the sensational conditions of his adoption. He assumed his birth parents were unmarried and he was born ‘illegitimate’: but discovered subsequently that they were married. His birth mother was a ‘serial rejector” of her own children, and had placed two other children also for adoption.

We all drank pretty heavily in those Fleet Street days of the 1960s and 70s, but David succumbed, later, to chronic alcoholism. The trauma of war experience, as well as a ‘feeling of dispossession’, hadn’t helped. Yet, despite his evident anger, David was a lovely man, often cheerful and funny. He was latterly married to another friend of mine, the feminist Rosie Boycott (a descendent of Ireland’s famous Captain Boycott).

He died in 2004, from lung cancer, aged 67. David had three kids from two marriages and a relationship and they are all just fine. Life involves suffering, but life renews itself too.

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny David Leitch

David Leitch