The town of Oberammergau (the district “above the river Ammer”) is situated in the Bavarian Alps of Southern Germany. It is best known world-wide for its decennial Passion Play. The 42nd Oberammergau presentation of the play opened on May 14, 2022 and performances will continue up to October 2, 2022.

According to the local legend the staging of the play started with a vow.

Plague

In 1632 the plague was raging across Europe, including the village at Oberammergau. People sought help in prayer and vowed: “If the dying stops, every 10 years we will stage the play of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ.”

The historical record states that by the early 1630s the many and diverse mini-kingdoms and statelets in Germany were devastated and overrun with infectious diseases as a result of the 30 Years War. This was particularly the case in Bavaria.

Initially Oberammergau was spared from contagion by diligent vigilance until the Church fair that fatal year when a local man, named Kaspar Schisler, brought the plague into the village. The community gathered and prayed for an end to the plague.

They also presented a Passion Play and promised to present it every 10 years thereafter. This the Oberammergau villagers have done with a few exceptions; namely the periods of World War I and World War II. And recently the Covid 19 pandemic has caused it to be postponed from 2020 to 2022.

I attended the Passion Play in 1960. I did so courtesy of Harold Ingham of Ingham Tours, London. He hired me to lead a pilgrimage from London to the Eucharistic Congress in Munich, which would also take in the Passion Play. The group of more than 30 consisted mainly of Catholics, with some Protestants from a few different denominations. For a final briefing Ingham invited me to spend the night before departure at his luxury home situated at Harrow on the Hill, near the famous public school.

Attendance at the Congress was an inspiring experience for all the members of the group. We were accommodated in the homes of German families. I was the guest of an engineer and his wife, a teacher. They were both Lutherans and did not have a family. Both spoke very good English which presumably was one reason why they had been invited to host a visitor or visitors to the Congress. They were natives of Hamburg in the north of Germany but in the chaos of the war ended up in Southern Germany. Their sharing this information with me was the extent of our conversation about the war.

In Munich we had a ring-side seat at what was then known as the ‘Economic Miracle’. At war’s end Germany’s economic and social fabric was at the level of the stone age. The Chancellor, Dr Konrad Adenauer, and his administration urged their fellow-citizens to prioritise the restoration of the roads, bridges, railway infrastructure and centres of industry. They responded valiantly to the appeal and with the support of the US-sponsored Marshall Plan by 1960 Germany had become once more one of the world’s leading industrial nations. One noticeable feature of this development was that all residential buildings or shopping centres had been re-constructed in a minimalist style. Thus, the home of my hosts was strictly functional with not a picture or ornament in sight.

Programme

The programme of the Eucharistic Congress was carried out with Teutonic efficiency. Not a few of the sessions featured the green shoots of the then coming radical liturgical movement which preceded the Second Vatican Council. On one occasion, while escorting my group on a suburban train to the Congress centre, I met my friend Enda McDonagh. Enda, who was two years senior to me in Maynooth, I learned was at that time pursuing studies in Canon law at the University of Munich.

Oberammergau and the Passion Play were quite a contrast to Munich and the Eucharistic Congress.

There were very few frills attached to the village and its Passion Play in 1960. Centuries-old features of the play were observed. Everyone in the village had a role in the play as actors, members of the choir, providing the music, the text and every other aspect of its production. Also no one outside the village was involved in the play.

Taboos

Centuries-old taboos were also associated with the main actors: Christ, Mary, Judas and Mary Magdalen. The lines in the text condemning the Jewish elite, who were responsible for the death of Christ in Roman-occupied Palestine, were unrestrained. The running-time of the play was seven hours and it was presented in two sessions in the out-of-doors. There was no doubting the intention of the participants in the play to treat the subject-matter with appropriate grace and respect. Thus the play was an authentic, if at times amateurish, presentation of the Gospel story.

The Oberammergau Passion Play in 2022 is different in many ways from its predecessors. The town now has a population of well over 3000. To ensure a high standard of performance non-residents of the town fill some of the major roles. To this end outsiders have also been added to the choir and the orchestra. Much of the text has been rewritten and updated and lines which might suggest a hint of anti-Semitism have been excised. The general cast is diverse. Besides the townspeople, the cast of 1,800 includes refugee children and non-Christians. The play is presented in a splendid theatre in two sessions, lasting in all just five hours.

Portrayal

The Passion Play in 2022 is no longer just a step-by-step simple portrayal of the Passion. It is a scholarly presentation with numerous allusions and references to the Old Testament. The dialogue of the major figures is nuanced to highlight the dilemmas they faced. This is particularly the case with Judas Iscariot. The sophisticated production is one which is truly fit for our times.

The 2022 Passion Play is different from its predecessors, yet essentially it remains the same. It continues to tell the greatest story ever told, namely that Jesus Christ was born, lived, suffered, died and rose again for the love of every person born into this world.

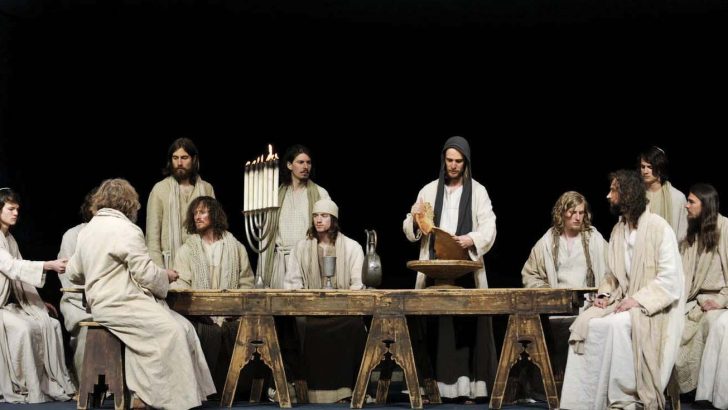

Jesus breaks the bread at the Last Supper.

Jesus breaks the bread at the Last Supper.