In the years immediately after the ending of the Great War, or the “War to save civilisation” as WWI was once called, Europe and then the wider world became aware of the existence in a remote village in Southern Italy of a priest for whom the most extraordinary claims, not just of piety, but of miracle-working, were being made.

He was also a stigmatic; a man marked with the wounds of Jesus on the Cross, the only ordained priest moreover who was thus singled out.

This man was Padre Pio, the centenary of whose stigmatisation is celebrated this year. The village was San Giovanni de Rotondo, where a basilica was eventually dedicated to him after he was canonised by Pope John Paul II.

For much of that century his life was of absorbing interest to readers of the press, of magazines and books, and eventually for television viewers when the most modern of the media finally caught up with him.

Who was Padre Pio?

He was born Francesco Forgione, on May 25, 1887, in Pietrelcina, a town in the southern Italian province of Benevento. He was given the name in religion of Pius (in Italian: Pio) when he joined the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin in January 1903, at the age of 15, in honour of Pope St Pius I, whose relic is preserved in the Santa Anna Chapel in Pietrelcina. He took the simple vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience.

With difficulties through lack of capacity and serious illness he struggled through his studies for the priesthood. In 1910 Pio was finally ordained at the Cathedral of Benevento. Four days later, he offered his first Mass. His health being precarious, he was permitted to remain with his family until 1916 while still retaining the Capuchin habit.

On November 15, 1915, he was drafted into the Italian army – Italy had finally entered the war on the Allied side in May – and in December was assigned to the Medical Corps in Naples. Due to his poor health, he was continually discharged only to be recalled. Then in March 1918, he was definitively declared unfit for military service. He had seen only 182 days of military service, none of it on the front line.

On September 20, 1918, while at Mass Padre Pio fell into an ecstasy. When he recovered he found he carried on his hands and feet: these bodily marks, the pain, and the bleeding were in locations corresponding to the traditional places of crucifixion wounds of Jesus Christ – though many historians and doctors argue they do not agree with the actual Roman technique of execution in which the nails were driven through the wrists and not the palms.

These mystical phenomena (and rumours of others more controversial) continued for 50 years. They would only vanish at his death. The blood flowing from the wounds was said to be scented, the ‘odour of sanctity’ often mentioned in legends of earlier saints.

The legend of a new saint spreads

Though Padre Pio later said he would have preferred to suffer in secret, by early 1919 news about the stigmatic friar began to spread in the local province.

By 1920 news of his existence and his marks, seen by the devout as signs of God’s favour, had even reached Australia. There the Southern Cross noted in November 1920: “That there is a priest in Southern Italy marked with the stigmata is scarcely known at the moment.”

This would soon change.

The paper reported what many believed that his wounds “gave him more pain on than usual on every Friday”. Medical men and surgeon had examined his wounds “without being able to come to any opinion on them, except that they cannot be explained them from a natural standpoint”.

These years were summarised in an article by the London Observer’s Rome Correspondent in the summer of 1923, which I will quote to give some flavour of what was then being written about this modern St Francis.

“On the Adriatic side of Italy, beneath the wooded slopes of Monte Gargano, lies the little township of San Giovanni Rotondo, and there, in a convent of Capuchin friars, lives, II Santo, Padre Pio of Pietralcina.

“When Padre Pio first came to the convent, some six or seven years ago, there was nothing to distinguish him from any other monk, except that he was even quieter, perhaps, than the rest, and a strict observer of the Capuchin rule, which is that of the Franciscan order in its utmost rigour.

“On September 20, 1918, while Padre Pio was praying, he fell into an ecstasy, and when he recovered, it was to find that, like St. Francis, he bore the marks of the stigmata on his hands, feet, and left side. Doctors came to visit him from all parts of Italy, but not one of them could explain the phenomenon.

“After this his fame as a saint spread gradually but surely. It is said that he possesses a miraculous gift of healing, and the power, common to many saints, of becoming invisible at will, and of appearing suddenly in some distant place where his help is needed, at an hour when it is authentically known that he has never left his convent cell.

“San Giovanni Rotondo has become a place of pilgrimage to which people flock from all parts of the world, and more than one crowned head has made his way to the little Apulian town to seek help or comfort from ‘the Saint’.

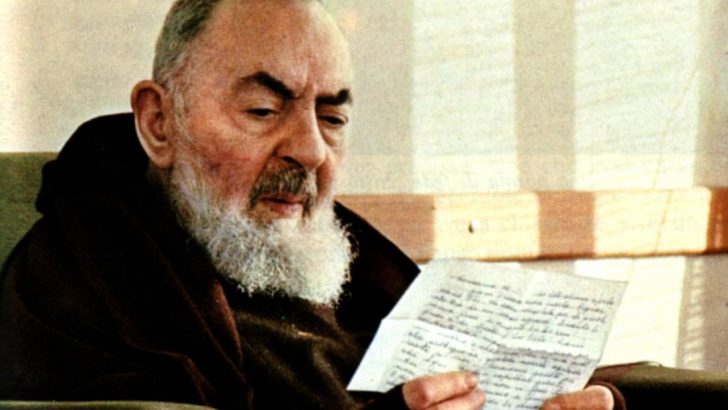

“Padre Pio himself lays no claim to miraculous gifts; he is the most modest and simple of men. He has a mild, ascetic countenance, with a fair beard, and hair turning grey on his high temples. His eyes are kind yet piercing; his voice has a peculiar charm.”

Rome speaks, but is ignored

But the admirers of Il Santo were greatly shocked later that year by an announcement in L’Osservatore Romano to the effect that “the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office, having made inquiry into the facts attributed to Padre Pio of Pietralcina, has come to the conclusion that there is nothing supernatural about them, and the faithful are, therefore, exhorted to act in conformity with this declaration”.

This verdict was the result of an inquiries undertaken, among others, by Monsignor Paschal Robinson, later to be the first Nuncio to Ireland.

At San Giovanni Rotondo this announcement caused consternation. When it was rumoured that his superiors intended to change his place of residence, the population rose up and went in procession to the monastery clamouring for Padre Pio. They refused to leave until he had shown himself to them at a window.

To prevent a secret removal of Il Santo, 40 local Fascists undertook to guard the building by turns, day and night. The involvement of Mussolini’s bully-boy Blackshirts (who had captured the Italian state the previous October) sets the period scene exactly.

It was in the 1920s that the informal pilgrimages to see and confess to Padre Pio began and grew. These were widely reported, even in such social magazines as The Sphere in England. These events disturbed the local and Vatican authorities.

The Holy Office issued a decree in the autumn of 1926 which was again widely reported, forbidding all Catholics “to print, read, sell, lend, borrow, translate or diffuse pamphlets about him”.

The little booklets. all without an imprimatur of course, were placed on the index. Further Catholics were forbidden to visit or in any other way communicate with Padre Pio.

Little affect on the faithful

Through the 30s, the devotions only increased despite the social and political conditions of Italy. Allied forces entered San Giovanni in 1943 and soon after enthusiastic articles from US soldiers began to appear in Catholic publications in the States, where enthusiasm for Padre Pio increased.

In 1950 the Holy Office placed eight books in Italian, the work of Padre Pio enthusiasts, on the Index. This was later followed by a serious warning against various ‘prophecies’ of universal doom then being attributed to him.

The Catholic Standard in Dublin carried the headline ‘Don’t be scared’ over an article about these rumours of the “terrible calamities that are about to happen, and strange signs in the sky” – all the usual claims derived at third hand from the Apocalypse.

These pamphlets were in English, Italian, French, Hungarian, and Spanish. Letters asking about the claims from around the world poured into San Giovanni, according to one of Padre Pio’s secretaries, an American Fr Dominic OFM Cap.

In Italy this was a period of post-war poverty and an active Communist Party; in the world at large Churchill had inaugurated the Cold War with his infamous “Iron Curtain” speech at Fulton, Missouri.

Now that Russia had atom bombs, fears of the world coming to an end were natural enough. But such books and pamphlets just preyed on people’s fears for profit.

Il Santo becomes a controversial figure

Profiting from Padre Pio at this time took a new turn. The US in order to simplify the invasion of Sicily had restored the Mafia to its traditional reactionary power there. Now the ‘Honoured Society’ extended its activities, having been involve since 1870s in fake relic mongering, sent what Norman Lewis described as “a commando unit” to San Giovanni to take over the lucrative business associated with Padre Pio – by 1968 two million a year would be coming to San Giovanni.

Accommodation and shops were in Mafia hands. Pilgrim buses would be met, and the pilgrims, who perhaps spoke little or no Italian, were carried off to visit and leave offerings with bogus Padre Pios.

These scandals culminated in a Vatican investigation in 1960, which exonerated Padre Pio himself, who showed ‘humility and perfect obedience’, but was indifferent to the racketeers. Huge sums of money from around the world – often £2,000 a day – flowed in to the finances of the hospital that Padre Pio had founded in 1956, when he was relieved of his vow of poverty.

But it was in the 1950s and 60s too that the devotion to Padre Pio really developed. During the 1950s the setting of parish prayer groups was also being popularised in Ireland through lectures by the Dominican Fr P. W. Pollock, the Prior of Limerick, and others.

A unique record

By an extraordinary chance, in the last months of 1968 Padre Pio was persuaded to grant access to Mischa Scorer, a film documentary maker from the BBC. The cameras followed him for what were in fact to be the last months of his life.

The film was broadcast on January 30, 1969, little more than four months after his death. It was written and narrated by Patrick O’Donovan, the distinguished correspondent of the London Observer, a respected Catholic journalist of the day.

The critics was warm: “This startling study of a saint”, in the words of the Sun, was according to the Irish Times, “the most remarkable documentary for some time”. It won first prize at the Christian Television Festival in Monte Carlo as well. It is difficult to imagine it being made today.

Having avoided the traditional press all his life, Padre Pio’s days were now preserved for posterity, thanks to the latest manifestation of the modern media. It would give even an agnostic pause for thought.

Padre Pio, on the whole, was treated very well by the general run of the press, better treated than in the publications of his uncritical admirers and his cynical disbelievers.

But in the end all that did not affect his beatification or canonisation, which depended on personal testimony privately taken and on the miraculous favours granted through the intercession of the priest to the sick and distraught to whom Padre Pio had dedicated his life, or rather as some would now like to say, his eternal love.

Some important books

Those who want to learn something of contemporary views about Padre Pio might read the publications of Fr Charles Mortimer Carty; these belong to the mid 1950s, but are still available from Tan Books in the USA.

A book from the following decade which was widely read and translated was The True Face of Padre Pio (Souvenir Press, 1961) by the Polish writer Maria Winowska.

Anyone seeking some insight into the mysterious matter of the stigmata can still not do better than read the important classic book by the English Jesuit scholar Fr Herbert Thurston, The Physical Phenomena of Mysticism (Burns Oates, 1952; reprinted by White Crow Books, 2013, £14.99), which concluded the career of this sound and sober investigator of all kinds of mystifications by both Catholics and their opponents.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Padre Pio

Padre Pio