Irish links to the famous Capuchin date back to the 1920s, writes Colm Keane

To the Irish setting out for San Giovanni Rotondo in the 1950s, it must have felt like the ultimate pilgrimage. They first travelled long journeys by air in old prop planes. They then wound their way by slow trains and battered old buses as they climbed into the remote and inhospitable Gargano Mountains in the spur of Italy. Walking up the final stretch of dirt track, tired and hungry, they arrived at the isolated 16th-Century friary of Our Lady of Grace on the outskirts of San Giovanni Rotondo.

It was unlike any other journey these Irish pilgrims had undertaken before. What took them so long was the sheer magnitude of the trip. In those days, Italy seemed a world away, cut off not only by distance but by the high costs of travel.

Outings to Lough Derg and Knock were the height of it. For some people, however, religious conviction was a compelling force. Their search for spiritual meaning brought them to Padre Pio.

Visitors

One of the earliest Irish visitors was a Dublin woman, Mairead Doyle. In later life, she recalled how, on her 1950s visit, she travelled on mule tracks, with mud up to her ears. Her first act was to visit the friar’s 5am Mass. “She was very taken with his spirituality,” her niece, Mary Briody, recalls. “She said you couldn’t take your eyes off the altar during Mass. She said that his eyes seemed to penetrate through you. She made herself known and then she got in to see Padre Pio.”

Following that visit, Mairead became a personal friend of the stigmatic and dedicated herself to promoting him in Ireland. She travelled the country, showing films.

She also set up prayer groups, the first being established in 1970. She ran two pilgrimages a year to San Giovanni, and that was on top of her work as a lecturer in shorthand and typing in Dublin.

She also sought a cure from the friar. “When my sister Deirdre, who was the youngest in the family, was born she had three cerebral haemorrhages,” Mary Briody recalls. “The doctors didn’t give her any hope. Mairead had this relic of Padre Pio at the time and she put the relic on my sister and sent a telegram to San Giovanni. Of course, Deirdre did get better. So Mairead wrote to, or sent a telegram to, Padre Pio and said she would bring my sister over when she was four. Padre Pio’s reply was, ‘I’ve already been with Deirdre!’”

Mary O’Connor, from Cork, also visited Padre Pio in the 1950s. She was seeking a blessing for her young son. “He gave me his hands to kiss, he put his hands on my head and he put his hands on my boy,” Mary, who was deeply moved by her meeting with the friar, recollected.

“I looked into his face and I got an awful fright. He looked supernatural. He was different from any other living being I have ever seen. He literally shone and his eyes were remarkable. He was pale-featured, but he had a glowing expression.

“The whole thing had a huge effect on me. I was so startled that I handed over the child to my husband and I ran out of the church. I ran down the hill and I was hysterical. I worried that I had offended God all my life. I felt, ‘If God is anything like Padre Pio, how could I have ever offended him?’”

*****

It was inevitable that accounts of miracles would soon surface in the Irish press. The first was reported by Mona Hanafin, from Thurles. In 1964, she travelled to San Giovanni Rotondo with one aim in mind: to save her life. She was seriously ill, having just been diagnosed with cancer.

A long series of hospital stays and medical interventions had failed to resolve her problem, and time was running out. With a major operation pending, Mona decided to place her life in the hands of Padre Pio.

“We were all lined up on either side of the pews and I was at the altar rails,” she recalled of her meeting with the stigmatic. “Padre Pio was going to pass up through us all. The custom was that he would give you his hand and you would kiss it. I was looking at him and saying in my mind, ‘If you think I’m good enough would you put your hand on my head and bless me.’ He did.”

Explanation

Although there was no instant cure, contrary to all expectations Mona not only recovered but, once back in Ireland, her doctor discovered that her cancer was gone. He was baffled and could offer no explanation. An operation, he said, was no longer necessary. At the time of this author’s last discussion with Mona, well over half a century later, the cancer had not come back.

Although these women were the first Irish people to undertake individual pilgrimages to Padre Pio, they weren’t the first Irish people to meet him. The Dublin-born Vatican diplomat Dr Paschal Robinson was most likely the first to encounter him in the 1920s. Many Americans with strong Irish roots – including his lifelong devotee, Mary Pyle – also made his acquaintance in earlier decades. In particular, Irish soldiers who fought with the Allies during World War II paid visits to the friary at San Giovanni.

Among those travelling up the dirt track was a young Belfast-born chaplain by the name of Fr P. Hamilton Pollock. Attached to the Royal Air Force during World War II, he had ended up with Bomber Command near the town of Foggia, just seven miles from San Giovanni Rotondo. From there the Allies consolidated their advance up through Italy on their way to Rome.

One day, in 1943, an RAF medical officer mentioned to Fr Pollock that Padre Pio was living nearby. The following week, on a duty-call to San Giovanni, he decided to visit the local church to pray. On entering, he noticed that one other person was inside, deep in contemplation. “His cowled head was inclined forward, his hands buried deep in the loose sleeves of his habit,” he later recalled.

Quietly walking up the church, Fr Pollock approached the robed figure to ask where he might find Padre Pio. He tapped him twice on the shoulder but there was no reply. A third time he tapped and this time the figure slowly looked up, his concentration broken but his eyes still blank. It was clear to Fr Pollock that he was in the presence of someone who was “not of this earth….very far removed from this world”. He instantly knew it was Padre Pio.

Over the next two and a half decades, Fr Pollock became one of Padre Pio’s closest personal friends and visited him on many occasions. He also brought news of the future saint back to Ireland, encouraging others to travel to see him. Among those who visited was the Donegal-based former wartime spymaster, John McCaffery, who had headed up the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) in Bern during World War II.

Born in Scotland to Donegal parents, McCaffery had recruited resistance fighters in occupied countries, organised sabotage campaigns, and collected intelligence during the war. Like Fr Pollock, he too became a personal friend of Padre Pio. They would talk together, share jokes; at times even sit in the same stall together in the choir-loft of the church. McCaffery was soon given the privilege of entering the monastery on his own and without special permission. He was also afforded the honour of serving at Padre Pio’s Masses on seven occasions.

McCaffery believed he received a cure through Padre Pio’s intercession. Since his wartime exploits, he had suffered serious heart trouble, involving palpitations, head pain and a partial stroke.

During a Mass in San Giovanni, he mentally begged Padre Pio to help him avoid another stroke, which he feared to be imminent. After the Mass, Padre Pio held McCaffery’s head in his hands and pressed it against the wound in his side. He did the same again on two further occasions. No heart trouble was ever experienced again by McCaffery.

Despite the Irish visits to Padre Pio in the 1940s and ‘50s, it wasn’t until the package tour revolution of the 1960s that Irish people visited en masse. Suddenly, all-in, cut-price pilgrimages were on offer, most of them organised by Joe Walsh Tours. Throughout the decade, the company ferried thousands of Irish people to Rome and onwards to Padre Pio. With employment booming and emigration falling, people had the money to pay for the new form of travel.

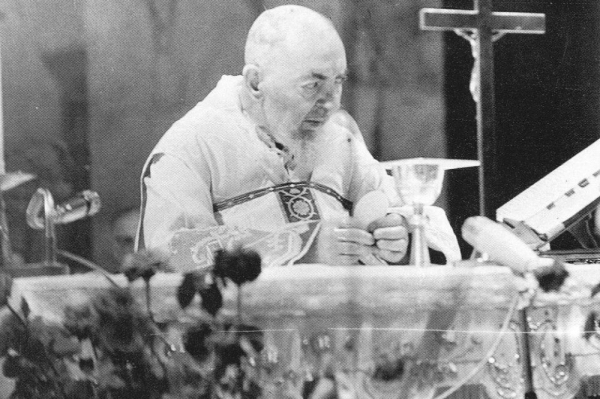

They attended Padre Pio’s Masses, witnessed his stigmata and received his blessing. Although the friar was ageing fast, all who met him or saw him were left with indelible memories.

*****

Tom Cooney, from County Clare, was one of those fortunate enough not only to be blessed by the future saint but to kiss his wounded hand. He waited along with 27 other men in a room in the monastery. It was ‘men only’, he was told, in keeping with the rule of the friary. The men knelt there nervously, their voices subdued, each one hoping that he might be singled out by the friar. An atmosphere of anticipation preceded the event.

“There was a great feeling of holiness there,” Tom said of the arrival of Padre Pio in the room. “He was a man that could read your mind and soul. He walked past each one of us. There was no ceremony. He just stood for a second before everyone, and everybody touched his habit. I was the only one he handed the wounded hand to, to kiss. I didn’t say anything to him; I was just thanking God to be in the one room with him. I couldn’t have asked for more.”

A tour party of 83 Irish pilgrims were also present around the time of Padre Pio’s death. They had been among the last to attend his Masses, receive his blessing and be greeted individually by the friar. They were returning to Rome when the news of his death was announced. The late Kay Thornton, who was with the Irish party, came back to San Giovanni, travelling via Foggia on the overnight train.

“I was determined to go back, although most people stayed in Rome,” Kay reflected. “I kissed him laid out in the coffin. It was unbelievable how many people were there. You couldn’t move with the people. People were queuing night and day to pass the coffin.

“There were so many coming, and the doors had to be closed for the funeral. The people nearly went crazy because they couldn’t get in. It was very moving. It was very special to have been there.”

*****

Cork woman Mary O’Connor, who we heard from earlier, had arrived in San Giovanni a few hours before Padre Pio died. She was with her husband Dan and their children, plus some other young children, too. “The only thing I said was, ‘He’s suffered so much and he’s gone to heaven!’,” Mary recollected. Dan said: “Let’s get the children up and dress them and we’ll go up to the church and see what’s happening.” Padre Pio’s body was already there, in his coffin, up in the altar area.

“I then said to Dan, ‘Would you stay with the children? I want to get nearer to Padre Pio.’ I went to the back of the altar and I got in. As I got there, they were changing the candles on the coffin. I asked the priest: ‘Would you mind giving me one of the candles?’ He gave one to me. Pieces of it have gone all over the world.”

On Thursday, September 26, 1968, 60,000 people lined the streets as the body of Padre Pio was borne through San Giovanni.

The entire town shut down. Black-bordered flags flew at half mast. Hundreds of veiled women, dressed in black, knelt as the open hearse bearing the coffin passed by. The body was eventually placed in the crypt of the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Kay Thornton, who had remained in San Giovanni through those final days, was deeply touched. ‘‘You never forget Padre Pio,” she told me. ‘There was never anyone like him before. He suffered dreadfully all his life. Every single moment of his life he was suffering from those bleeding wounds and they were so sore. He must have been a special person even to survive that.

“He was a profound man, like nobody I ever met. I am a very lucky person to have met him. He once put his hand on my head and that was the most wonderful thing that ever happened to me. He lets you know when you are not pleasing him and then he helps you when you do something right. He is always with you, he is always there.”

Perhaps we should leave the final words to Mona Hanafin, that wonderful Tipperary woman whose cure followed her visit to San Giovanni and who later worked tirelessly on the saint’s behalf in Ireland.

“Following his death he was such a loss,” she concluded. “His whole life was dedicated to saving souls. He was a tireless confessor. You had St Francis and St Anthony but in our times of trouble you had Padre Pio. He was special, he was just sent to us for our time. And why did he do it?

“He didn’t do it for himself; he did it for us, for mankind. I definitely regard him as the greatest mystic ever.”

Colm Keane has published 27 books, including seven number one bestsellers, among them Padre Pio: The Scent of Roses, Padre Pio: The Irish Connection, and his most recent book Padre Pio: Irish Encounters with the Saint, published by Capel Island Press, retailing for €14.99.

Padre Pio celebrating his last Mass which was attended by many Irish pilgrims.

Padre Pio celebrating his last Mass which was attended by many Irish pilgrims.