We have to keep hoping in the midst of crises and in the face of our fears, writes Fr Thomas Casey SJ

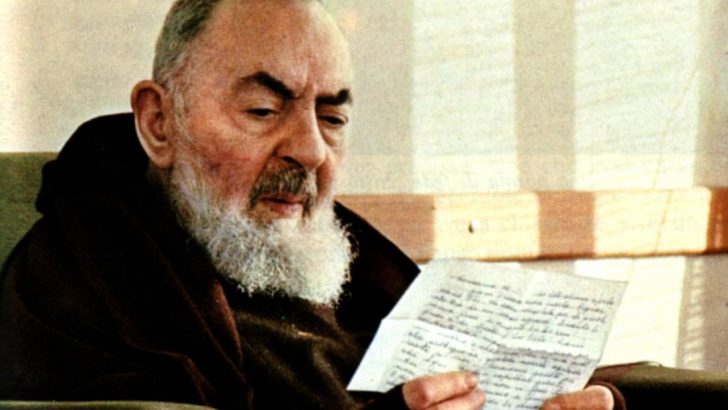

“They’re not ornaments you know,” Padre Pio once exclaimed to a zealous pilgrim who grabbed his hands so firmly that the Capuchin saint began to writhe in pain. Padre Pio suffered from the stigmata – wounds in his hands, side, feet and shoulder – and he also suffered from the publicity they brought. But he didn’t lose his sense of humour, and after a medical examination that seemed to go on forever he joked: “It’s better to be a mouse between two cats than Padre Pio between two doctors!”

Born Francesco Forgione in 1887 in Pietrelcina, he spent most of his priestly life in the town of San Giovanni Rotondo. Canonised by Pope John Paul II in 2002, Padre Pio’s feast day is September 23, the date of his death in 1968.

Padre Pio is probably the most loved saint in Italy, a kind of modern-day Francis of Assisi. The devotion of Irish people for this revered Capuchin friar almost equals the fervour of the Italians, and many of our compatriots have taken this stigmatist and mystic to their hearts.

Black hair

It was only when I visited San Giovanni Rotondo that I began to see how deeply he still touches people. At Padre Pio’s tomb in the crypt of the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie (St Mary of the Graces), people of all ages knelt and sat in prayer.

A young father with an untidy mop of black hair pushed a buggy toward the railing surrounding the tomb. He prayed for a few moments, before hastily genuflecting as he turned to go. In the church above, a young family entered. The father, a swarthy figure in an ill-fitting jacket, walked up to a side-altar, with his wife and little daughter a few steps behind. He shifted awkwardly on his feet as he fingered a bouquet of flowers in his hand, before placing it next to a large squat candle. He blessed himself and, kissing his right finger, walked back outside with his family.

Padre Pio’s most obvious wounds were the stigmata, which continued to bleed for 50 years. But he also suffered from periods of darkness and desolation, moments where he felt “pitched past pitch of grief”, in the words of Gerard Manley Hopkins, and wondered what his life was all about and where it was going.

It was in September 1918, just a couple of months before the end of the First World War, that Padre Pio received the stigmata in a mystical vision…”

Maybe that’s why so many people feel they can bring him their own questions and their own inner struggles. They intuitively know that Padre Pio kept hoping against hope. Although he hoped that the sufferings and difficulties he experienced weren’t the final word, he didn’t know how and when they would clear up.

He didn’t demand that God would resolve everything in a particular way and by a particular deadline. And yet no matter what happened, and even when things became worse for him instead of better, he kept hoping. Nothing shook him from hoping: that’s what gave his hope such astonishing power.

***

It was in September 1918, just a couple of months before the end of the First World War, that Padre Pio received the stigmata in a mystical vision after celebrating Mass. He was 31 years old at the time. Christian tradition understands such phenomena as signs of identification with the suffering Christ. And down through the ages some Christians have opened themselves up to God so generously that they have become identified in this intimate way with the sufferings of Christ.

But when Padre Pio’s stigmata were brought to the attention of medical experts, several doctors doubted their authenticity. Various theories were put forward to explain them – some claimed they were psychologically produced, others maintained they were self-inflicted lesions.

Still others wondered whether they were the result of deep trauma. Gradually a deeper wisdom won out: the conviction that Padre Pio’s stigmata pointed to a mystery beyond any medical explanation.

During my brief visit to San Giovanni Rotondo, I noticed few people who were physically incapacitated. Perhaps those who came to pay their respects had wounds that were not so visible: stigmata I could not see. I wondered had they broken relationships, mood disorders or difficult careers.

Ordinary people

It struck me how much Padre Pio still touches the lives of ordinary people – and not always people you would expect to see in church, yet people who want something real and believe that Padre Pio can help them acquire it.

Suffering is one of the words that comes to mind when we think of Padre Pio. Is there a message in this for Catholics in general?

The sight of Padre Pio undergoing such a visible crucifixion may just be a prophetic sign that the Catholic Church has to undergo its own suffering, its own death, and not the glorious one for which it might have wished.

But instead a journey it never anticipated – the slow sapping of its energy, the helplessness of feeling overwhelmed, a difficult path where the light of the Resurrection is only dim and distant, where “love is not a victory march – it’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah” (Leonard Cohen).

But suffering is not the only word or even the principal word that comes to mind with reference to Padre Pio. He was above all a man of hope. This is expressed well by his famous and oft-quoted phrase: “Pray, hope and don’t worry.”

Despite his stigmata, the Crucifixion was not the last word for Padre Pio. Yet 2,000 years ago it appeared that way to many of Christ’s disciples, and that’s why they lost hope in the immediate aftermath of his death.

Gradually a deeper wisdom won out: the conviction that Padre Pio’s stigmata pointed to a mystery beyond any medical explanation”

His mother Mary, on the other hand, kept hoping. She knew during the darkness of Holy Saturday that the Resurrection of Jesus appeared totally improbable. But her hope didn’t depend upon probability assessments.

Her hope depended upon God, and that’s why she could trust that new life, although seemingly beyond reach, was nevertheless possible. Padre Pio was always close to Mary, and shared her deep sense of hope.

God always calls us to hope. Left to ourselves, we can all too easily be undermined by the darkness in ourselves and in our world. Certainly we shouldn’t deceive ourselves by denying or discounting the messiness and dangers of life. But for all that, we can learn from the example of Padre Pio to keep hoping in the midst of crises and in the face of our fears.

If God were to write a message of hope to us today, perhaps he might write it in a way we least expect. Who knows, he may have already written it in the flesh and body of this saintly Capuchin friar.

Fr Thomas Casey SJ is Dean of Philosophy at St Patrick’s College, Maynooth.

A biography titled Padre Pio of Pietrelcina written by Fr Francesco Napolitano is available at Columba Books. Visit here

Padre Pio

Padre Pio