Ambassador Arkady Rzegocki

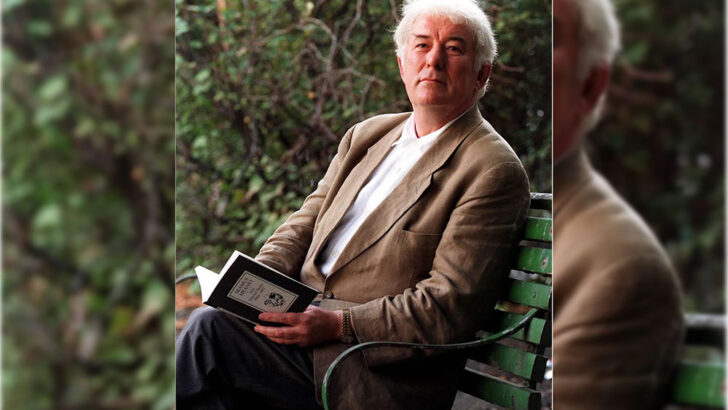

Twenty years ago, on a bright May day in Dublin, the whole of Ireland was a witness to a fine homecoming. The country that over the centuries saw many of its people leave and go into exile, this time welcomed at the clear waters of the Phoenix Park the ten European countries into the family of the European Union. It was a happy and fateful coincidence that it was the Irish who flew the flag of freedom, welcome and hospitality to the nations that were, in a phoenix-like manner, regenerating and being born again. Could there be a better-suited person to open the celebrations than Seamus Heaney, poet laureate and friend of Poland, who wrote a poem to mark the occasion and spoke with moral clarity and force on the day? He spoke of the sacred springs of poetry that rejuvenates the spirit and awakens the nations, of new languages and voices, of homecoming. It was 20 years ago, on May 1, 2004, during the Ireland’s EU Presidency, that ten countries, including Poland, became members of the European Union.

That day was an important, symbolic and deeply moving moment to the countries of Central Europe who had been deprived of freedom and opportunities to develop for 50 years as a result of the criminal actions of the two totalitarian regimes, Nazi Germany and Communist Russia. Ireland’s bard and Nobel prize laureate, Seamus Heaney, who was well acquainted with the culture and literature of the recently liberated part of Europe, who loved it well, proclaimed the rebuilding of strong ties between Western Europe and Central Europe. Twenty years on, his prophetic words read as fresh and inspiring as they did back then.

Connection

Heaney’s long-lasting friendship with the two Polish Nobel prize laureates, Czesław Miłosz and Wisława Szymborska, was particularly meaningful and symbolic in bringing our parts of Europe together. Heaney’s friendship with Miłosz was both emotional and intellectual, yet he often emphasized that Miłosz, who was his senior, was also his Master figure. This was a friendship that introduced Heaney to the poetry of Zbigniew Herbert as well as to the Czech and Slovak poetry. Heaney was the one who was able to relate with his extraordinary Irish experience to the equally fascinating experience of Poland and all of Central Europe. Interestingly, Heaney’s interest did not stop at the twentieth century, along with Stanisław Barańczak, a Polish poet and translator, he rendered into English one of the lyrical masterpieces of early Polish poetry, the Laments of Jan Kochanowski (2009), a cycle of lyrical poems that stand on a par with the Shakespearean Sonnets. In his humanity and poetic intuition, Heaney reached out to the poetry of one of the finest Slavic writers before the 19th Century, a poet whose monument was recently unveiled in the gardens of the thatched Anne Hathaway’s cottage in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The heritage, the experience and the legacy of Central European countries so closely associated with the ideas of freedom and solidarity”

The presence of Seamus Heaney who had spoken about the importance of poetry and art in the face of barbarism, at the enlargement ceremony at Phoenix Park, Dublin 20 years ago, shows how much Ireland and other countries of Western Europe have contributed to the global culture along with the nations of Central and Eastern Europe. It highlights just how dysfunctional, artificial, painful and harmful was the post-war division of Europe. Heaney knew all too well, also building on his own experience of growing up in Northern Ireland, that symbolically, only poetry can redress a wrong. This was, in fact, the title of his Oxford literature lectures delivered from 1989 to 1994. Thanks to his love for the poetry of Kochanowski, Miłosz and Herbert, thanks to his knowledge of the history of Poland and other countries in the region, the Irish poet was able to grasp and communicate to the wider world, the importance of cultural, political and intellectual re-integration of Central Europe. The heritage, the experience and the legacy of Central European countries so closely associated with the ideas of freedom and solidarity, found the best possible bard and advocate on the May Day of 2004.

Haven

Seamus Heaney came to Poland many times at the turn of the century, and he especially liked Kraków, the city of the two Nobel laureate poets, and also the city of Karol Wojtyła – Pope John Paul II. He spoke of the spirit of freedom and solidarity that he encountered in Poland, as well as of the sense of community and spiritual force, ideas so close to the Irish heart. In Kraków, he must have climbed the Wawel Hill to see the cathedral where the Polish kings and queens were crowned and are now laid to rest. Wawel is also a castle hill, the seat of the kings and their councils, the seat of the Polish-Lithuanian parliament. The history of Poland is, among other themes, also a history of civic engagement, as well as the history of local parliaments and self-governing cities. It is also the history of the elective kings and constitutions that introduced the rule of law, and of the longest-existing union in the history of Europe – the Polish-Lithuanian Union (1385), which created a multi-national, multi-religious and multi-ethnic state. Poland-Lithuania, though not without social and religious tensions, was famously the ‘state without stakes’, it prided itself in religious tolerance and its political system enabled Catholics, Protestants and the Orthodox to sit next to each other in the parliament. It was a state where European Jews found a safe haven that allowed their culture, education and religion to flourish for many centuries. It was also a state with the oldest Muslim community in Europe, the much admired and loved Polish and Lithuanian Tatars. Seamus Heaney, whose voice resonated strongly across the green of Phoenix Park 20 years ago, appreciated the unique contribution of Central Europe into the family of nations. As a friend of Miłosz who was born in Lithuania, he too, appreciated the rich heritage of Poland-Lithuania, its civic, democratic and tolerant past, and he knew well the history of the region’s modern struggle against imperialism, colonialism and exploitation.

The first abbot of the Tyniec monastery was Aron from Cluny, possibly an Irish Benedictine monk and bishop”

As Heaney made his way up to the Wawel Hill in Kraków, that overlooks the entire city, he may have been taken by the beauty of the river Vistula winding at the foot of the hill. I am not entirely sure, however, whether he knew of the oldest manuscript in Poland kept in Wawel that has a fascinating Irish link. It is a collection of 27 sermons, dating back to the late 8th Century, written and decorated in the best Celtic-Irish monastic tradition. A look at the four evangelists’ page in the Kraków Chapter manuscript immediately brings associations with a similar page from the Book of Kells at Trinity College Library. We owe it to the painstaking textual and art-historical research of Dr Małgorzata Krasnodębska-D’Aughton from the University College of Cork and Fr Jarosław Kurek OSB from the Glenstal Abbey monastery, that the Irish influences in both the decoration and content are now being confirmed. The ‘Kraków Book of Kells’ has been kept since the 11th Century in the Benedictine monastery of Tyniec near Kraków and was later transferred to the Wawel Cathedral Library. It is also around the village of Tyniec that items indicating the presence of Celts have been excavated. According to the monastic legend, the first abbot of the Tyniec monastery was Aron from Cluny, possibly an Irish Benedictine monk and bishop. Aron’s name also appears in the Kraków manuscript, albeit added much later. Based on the surviving evidence, scholars speculate that the Irish-Scottish monks went beyond Cologne, Salzburg and Vienna and reached Tyniec and Kraków on the way to Kiev. ‘Kraków Book of Kells’ is a witness of the significant cultural and spiritual role that the Irish benedictines played in the early years of the Polish statehood. The beautiful Latin sermons from the Kraków manuscript were no doubt an important element in the intellectual and spiritual growth of the Benedictine community and the Polish elites of the times.

Comraderie

As we celebrate the two decades of the happy home-coming of the Central European nations, we need to once again, in Heaney’s own words: ‘Move lips, move minds and make new meanings flare.’ It is perhaps another fateful co-incidence that the next Polish EU Presidency falls in 2025, and is followed by the Irish presidency in 2026. As we look for new life-enhancing meanings in our cultures, we should perhaps revisit the old treasures and inspire the dialogue of our cultures. The presentation of the Kraków manuscript next to the Book of Kells would be a celebration of our centuries-long cultural links.

Twenty years ago, the poet witnessed the rebirth of Europe whose farthest corners were once explored by the Irish people, the Irish monks who were the ambassadors of the new thought, new philosophical outlook, beacons of light. They came ‘with their gift of tongues past each frontier’ and found ‘the answering voices’ that they sought (Heaney). Today the ancient ties between the European countries are stronger than ever, the love of freedom and solidarity keeps us together. Poland and Ireland once again stand together as the two countries heavily involved in promoting peace, in aiding Ukraine under attack, in sheltering the war refugees and in actively supporting countries of the Eastern partnership and the Western Balkans. Poland and Ireland, the countries that have no colonial past, and that have on the contrary been exploited and colonised, increasingly engage in assisting and cooperating with the African countries.

Today the ancient ties between the European countries are stronger than ever, the love of freedom and solidarity keeps us together”

Today, 50 years after Ireland joined the European community, and 20 years after Poland’s EU accession along with the nine other countries, we see the importance of European cooperation and solidarity, we hear the strong voice of each country that speaks for freedom, independence and growth. I believe that members of the large Polish diaspora in Ireland, as well as all those who settle back in Poland, constitute a strong bridge that connects our two countries. As we are getting to know each other better, as we cooperate more closely economically, politically, and in terms of the humanitarian aid, we have to bear in mind that the ties between Poland and Ireland date back to the 10th and 11th Centuries, and that the patrons of Polish-Irish friendship and close cooperation are the giants of poets, Seamus Heaney and Czesław Miłosz. This is a legacy to celebrate.

Arkady Rzegocki is the Polish ambassador to Ireland

Poet Seamus Heaney.

Poet Seamus Heaney.