The passing of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI marks an important milestone in the history of the Catholic Church, in large part because of his role as a writer and scholar.

All his life Joseph Ratzinger was an intellectual figure, a continuing student of theology and philosophy. He once said that “his only real friends were his books”.

One can understand that feeling: they might have seemed to be unchanging voices, but with constant re-reading books express different things on different occasions.

Progressive

When the professed theologian first emerged he was seen as a friend of Hans Küng at one time and to be a part of a progressive edge of the Church. What altered this perception for many was his reaction to the events of the spring of 1968, when the student revolt in Europe and North America quite dismayed him, indeed terrified him: it seemed to threaten the very foundations of his mental world.

It seemed – as it was in some ways – a betrayal of the claims of intellectual discourse and debate that should be involved in the intellectual life, different views feeding on each other’s ideas, in which doubt rather than certainty should also be allowed for.

But the emphasis on ‘tradition’ especially in such matters at the Latin Mass with which he was associated, was to overlook the very important first passages of the Acts of the Apostle (2:5-12), which emphasised the use of the vernacular from the start in that upper room.

Changing

The changing Ratzinger became more certain, and less welcoming of other points of view, it seemed to some. But that raucous manner of interaction that dismayed the Tübingen philosopher decades ago is still with us, and still as harrying and hateful. He was right about its effects, but his solution of more rigid certainty seemed to some to strike out the sense of compassion that pervades the Gospel, the intercultural interaction symbolised by the Three Wise Men.

As a child of central Europe Ratzinger the student and teacher seemed to have little real sense of the other cultures of the world in any humane way.

When for instance he was the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the agency published a condemnation of the writings of Fr Anthony de Mello SJ, which revealed not only a lack of a sense of humour faced with the fables of the Indian Jesuit, but also perhaps a failure to fully apprehend the English in which it was written.

As an intellectual document it expressed a fear of other cultures, but not the strength of Christian belief. But his work from 1968 An Introduction to Christianity, serves to give an account of the Christian faith as encountered through the Apostles’ Creed, and will perhaps last beyond many other more of his topical books.

But all his life Benedict, whether as schoolboy, student, priest, bishop, cardinal or Pope, was always a writer. His output was huge.

But not all of these were actually written by him in the common understanding of the term. They were as often as not the outcome of meetings with journalists who recorded his answers to their questions, thus providing a running commentary on the common concerns of the day. It was a very different approach to teaching through encyclical letters, documents whose language is often found difficult by ordinary readers.

Approach

Benedict’s approach was direct and forceful and more adapted to the modern manner than many of those Vatican spokesmen whose grasp of English, surely the universal language of our day, seemed unsteady. What he expressed was certainty, rather than the anxious doubt that so many Catholics seem to feel these days.

On New Year’s Day, a pilgrim in St Peter’s Square – who had changed his holiday plans so he could pay his respects to the remains of the late pontiff – told a Canadian journalist, that though he had drifted away from the Church he returned to it under the influence of Pope Benedict. The Church is nothing if it is not tradition, said another: “Its teachings do not change.”

Traditionalist

But the man they acclaimed as a traditionalist had broken with tradition to resign the office of pope. This decision, as pope, to resign his office marked the Papacy as perhaps only another major executive role and not a divine office to be closed only by death.

He showed by this one act just how personal judgement of a pope changes tradition and alters the Church’s self-understanding.

He had, of course, witnessed the white martyrdom of Pope St John Paul II, during which a pope’s mind and body crumbled away before the eyes of a distressed world.

When his time came, exhausted by internal betrayal in the Vatican, and his own feeling of incapacity to cope with the crimes of which individual priests were being not only accused, but also convicted of, forced Benedict to make an historic change.

Journalists and commentaries speak of him leaving the Church a divided legacy. The legacy is surely quite clear: when a decision is clear it should not be avoided, it should be made, and that often enough the Church, like a great living tree, must change with the seasons if it is to grow. For this one act the future Church will find much to thank Benedict for.

Peter Costello

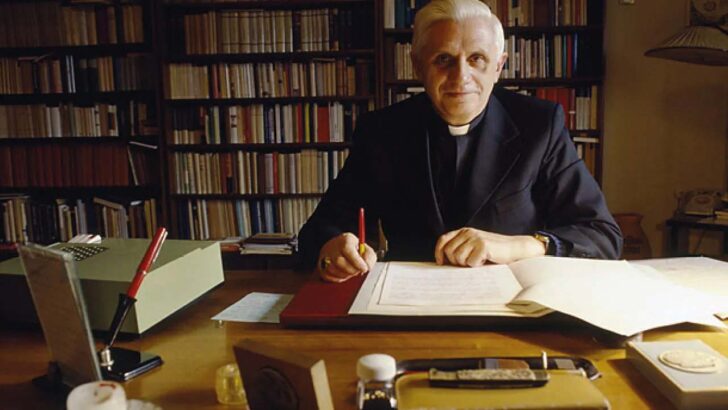

Peter Costello The younger Ratzinger, dedicated to study and writing.

The younger Ratzinger, dedicated to study and writing.