As the Church prepares to honour teenagers who lived lives of heroic virtue, the message is that holiness is for everyone writes Michael Kelly

During his long pontificate, St John Paul II canonised 482 saints – more than his predecessors had raised to the altars of the Church in the previous 600 years. His critics accused the Polish pontiff of being too quick to declare people saints, but John Paul II knew that the contemporary world needed more signposts to God rather than fewer.

His papacy saw not only the canonisation and beatification of historic figures, but also modern men and women who had lived lives of holiness in the midst of the modern world.

Both Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis have followed the model of proposing ordinary people who have lived extraordinary lives as models for Catholics to follow. It is a way of putting flesh on the idea of the universal call to holiness proposed by the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s.

The Church has also been adept at putting modern technologies under saintly patronage. St Isidore of Seville, for example, is the unofficial patron saint of the internet. Despite the fact that he lived more than 13 centuries before the world wide web was invented, his efforts to record every known thing earned him the title.

But, Isidore might have a rival for that accolade now that Pope Francis has given his approval for the beatification of an Italian teenager who was a computer whizz kid.

Leukemia

Venerable Carlo Acutis, who died in 2006, will be beatified October 10 in Assisi, Italy – the town made famous by St Francis and St Clare (patron saint of television).

“The joy we have long awaited finally has a date,” Archbishop Domenico Sorrentino of Assisi said in a statement at the weekend.

The teenager – who will be known as Blessed after his beatification – is currently buried in Assisi’s Church of St Mary Major.

He died of leukemia at the age of 15, and during his illness offered his suffering as a prayer for the Pope and for the Church.

He was born in London on May 3, 1991 to Italian parents who soon returned to Milan. He was known as a pious child, attending daily Mass, frequently praying the rosary, and making weekly confessions.

“Jesus was the centre of his day,” according to his mother AntooniaSalzano. She said that priests and nuns would tell her that they could tell that the Lord had a special plan for her son.

“Carlo really had Jesus in his heart, really the pureness…When you are really pure of heart, you really touch people’s hearts,” she said.

The date for the beatification was announced the same week as the feast of Corpus Christi and Carlo also had a great devotion to the Eucharist and Eucharistic miracles.

“It is beautiful that this news comes as we prepare for the feast of Corpus Christi,” Archbishop Sorrentino said. “Young Carlo distinguished himself with his love for the Eucharist, which defined his highway to heaven.”

The miracle that paved the way for his beatification involved the healing of a Brazilian child suffering from a rare congenital anatomic anomaly of the pancreas in 2013. The Medical Council of the Congregation for Saints’ Causes gave a positive opinion of the miracle last November, and Pope Francis approved the miracle in February.

Carlo was exceptionally gifted with computers. In Christus vivit, the apostolic exhortation published after the 2018 Synod of Bishops on young people, Pope Francis offered him as a model of holiness in a digital age.

“The news constitutes a ray of light in this period in which our country is struggling with a difficult health, social and work situation,” Archbishop Sorrentino said.

“In these recent months of solitude and distancing, we have been experiencing the most positive aspect of the internet — a communication technology for which Carlo had a special talent.

“The love of God can turn a great crisis into a great grace, the archbishop said.

Sainthood

Another Italian young man put firmly on the path to sainthood by Pope Francis is Matteo Farina who died in 2009.

Matteo died of a brain tumour and the Pope approved his heroic virtue last month and declared him venerable after a meeting with Cardinal Becciu.

Matteo grew up in a strong Christian family in the southern Italian town of Brindisi. He was very close to his sister, Erika.

The parish where he received the sacraments was under the care of Capuchin friars, from whom he gained a devotion to St Francis and St Pio of Pietrelcina (Padre Pio).

The postulator of Matteo’s cause for sainthood said that from a young age he had the desire to learn new things, always undertaking his activities with diligence, whether it was school or sports or his passion for music.

Starting at eight years old, he would go to Confession often and also had a passion for the scriptures. At nine years old, he read the entire Gospel of St Matthew as a Lenten practice and prayed the rosary every day.

When he was nine years old, he had a dream in which he heard Padre Pio tell him that if he understood that “who is without sin is happy,” he must help others to understand this, “so that we can all go together, happy, to the kingdom of heaven.”

From that point onward, Matteo said he felt a strong desire to evangelise, especially among his peers, which he did politely and without presumption.

He once wrote about this desire, saying “I hope to succeed in my mission to ‘infiltrate’ among young people, speaking to them about God [illuminated by God himself]; I observe those around me, to enter among them as silent as a virus and infect them with an incurable disease, Love!”

In September 2003, a month before his 13th birthday, Farina began to have symptoms of what would later be diagnosed as a brain tumour. As he was undergoing medical tests, he began to keep a journal. He called the experience of the bad headaches and pain “one of those adventures that change your life and that of others. It helps you to be stronger and to grow, above all in faith”.

Over the next six years, Matteo would experience several brain operations and undergo chemotherapy and other treatments for the tumour.

His love for the Mother of God strengthened during this time and he consecrated himself to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

In between hospitalisations, he continued to live the ordinary life of a teenager: he attended school, hung out with his friends, formed a band, and fell in love with a girl.

He later called the chaste relationship he had with Serena during his last two years of life “the most beautiful gift” the Lord could give him.

When he was 15, he reflected on friendship, saying “I would like to be able to integrate with my peers without being forced to imitate them in mistakes. I would like to feel more involved in the group, without having to renounce my Christian principles. It’s difficult. Difficult but not impossible.”

Eventually, the teenager’s condition worsened and after a third surgery he became paralysed in his left arm and leg. He would often repeat that “we must live every day as if it were the last, but not in the sadness of death, but rather in the joy of being ready to meet the Lord!”

Matteo died surrounded by his friends and family on April 24, 2009.

Francesca Consolini, the postulator of Farina’s cause, wrote on a website dedicated to the young venerable that in him emerged “a deep inner commitment oriented toward purifying his heart from every sin” and he experienced this spirituality “not with heaviness, effort or pessimism; indeed, from his words there emerges constant trust in God, a tenacious, determined and serene gaze turned to the future”.

Matteo often thought about the faith and the “difficulty of going against the current.” Concerned about a lack of good faith education for young people, he undertook this task among his own peers.

He once wrote in his journal: “When you feel that you can’t do it, when the world falls on you, when every choice is a critical decision, when every action is a failure…and you would like to throw everything away, when intense work reduces you to the limit of strength…take time to take care of your soul, love God with your whole being and reflect his love for others.”

Holiness

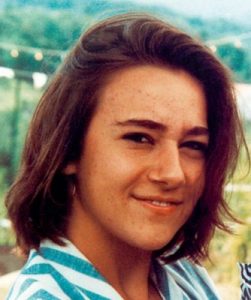

Another modern model of holiness proposed by the Church for veneration is Blessed Chiara Badano. She was born in 1971 in Sassello, Italy after her parents Ruggero and Teresa had prayed to be blessed with a child for more than ten years.

Even at the age of four, her parents said that Chiara seemed aware of the needs of others and she would sort through her toys to give some to poor children. Her parents reported that she would never give away just the old or broken ones. She invited less-fortunate people into the family’s home for holidays and visited the elderly at a retirement centre. When other children were sick and confined to bed, Chiara visited them. She loved the stories of the Gospel and loved to attend Mass.

When she was 9, Chiara became involved with the Focolare movement and its branch for young people. Focolare emphasises fraternity and unity among all people.

Chiara was very popular. She had a lot of friends, she played sports, and she loved to sing and dance. But when asked, she said she did not try to bring Jesus to her friends with words. She tried to bring Jesus to them with her example and how she lived her life.

When she was 17, Chiara learned she had a very serious form of bone cancer. Treatments were painful and unsuccessful. She became paralysed. One day someone asked her if she hoped to walk again, and her answer was no. When she suffered, she felt closer to Jesus. She even refused to take pain medication that would make her too sleepy to continue to live her life.

Despite her illness and being confined to bed, Chiara wrote letters and sent messages to others. Friends say she inspired everyone who she encountered with her faith and love for others. She gave all her savings to a friend who was becoming a missionary in Africa. When her life was nearly at an end, she said, “I have nothing left, but I still have my heart, and with that I can always love.”

Chiara died in 1990 and within nine years, the bishop of her diocese began the work on her cause for canonisation. Pope Benedict XVI declared her ‘Blessed’ in 2010.

“Only Love with a capital ‘L’ gives true happiness,” and that’s what Chiara showed her family, her friends and her fellow members of the Focolare movement, the Pope said at the time.

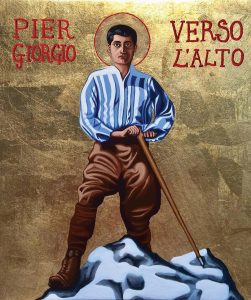

Chiara, Carlo, and perhaps one day Matteo, are to the decades of the 21st Century what Blessed Pier Giorgio Frassati was to the 20th.

Known as a ‘man of the beatitudes’ and patron of young adults, he saw many parallels between Catholic life and his favourite pastime, mountain-climbing. He would regularly organise trips into the mountains with his close friends with occasions for prayer, liturgies, and conversations about faith on the way up to or down from the summit. After what would become his final climb he wrote a simple note on a photograph: “Verso L’Alto”, which means “to the heights.” This phrase has since come to encapsulate his philosophy of mountaineering and his Catholic outlook on life and adventure.

Political activism

At an early age, Pier Giorgio joined the Marian Sodality and the Apostleship of Prayer, and obtained permission to receive daily Communion (which was rare at that time).

He developed a deep spiritual life which he never hesitated to share with his friends. The Eucharist and the Virgin Virgin were the two poles of his world of prayer. At the age of 17, he joined the St Vincent de Paul Society and dedicated much of his spare time to serving the sick and the needy, caring for orphans, and assisting the demobilised servicemen returning from World War I (1914-18). He decided to become a mining engineer, studying at the Royal Polytechnic University of Turin, so he could “serve Christ better among the miners,” as he told a friend.

Although he considered his studies his first duty, they did not keep him from social and political activism. In 1919, he joined the Catholic Student Foundation and the organisation known as Catholic Action. He became a very active member of the People’s Party, which promoted the Catholic Church’s social teaching based on the principles of Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Rerum Novarum.

What little money he had, Pier Giorgio gave to help the poor, even using his bus fare for charity and then running home to be on time for meals. A friend later wrote that the poor and the suffering were his masters, and he was literally their servant, which he considered a privilege. His charity did not simply involve giving something to others, but giving completely of himself. This was fed by daily communion with Christ in the Eucharist and by frequent meditation.

He was strongly anti-Fascist and did nothing to hide his political views. He physically defended the faith at times involved in fights, first with anti-clerical communists and later with Fascists. Participating in a Church-organised demonstration in Rome on one occasion, he stood up to police violence and rallied the other young people by grabbing the group’s banner, which the royal guards had knocked out of another student’s hands. Pier Giorgio held it even higher, while using the banner’s pole to fend off the blows of the guards.

Just before receiving his university degree, Pier Giorgio contracted poliomyelitis, which doctors later speculated he caught from the sick whom he tended. Neglecting his own health because his grandmother was dying, after six days of suffering Pier Giorgio died at the age of 24 on July 4, 1925.

On the eve of his death, with a paralysed hand he scribbled a message to a friend, asking him to take the medicine needed for injections to be given to Converso, a poor sick man he had been visiting.

St John Paul II, after visiting his original tomb in the family plot in Pollone, said in 1989: “I wanted to pay homage to a young man who was able to witness to Christ with singular effectiveness in this century of ours. When I was a young man, I, too, felt the beneficial influence of his example and, as a student, I was impressed by the force of his testimony.”

On May 20, 1990, in St. Peter’s Square which was filled with thousands of people, the Pope beatified Pier Giorgio Frassati, calling him the ‘Man of the Eight Beatitudes’.

In a world of celebrity where the internet and social media breaks people as quickly as it makes them, these young friends of God are a reminder to their peers that we are made for greatness rather than comfort. They also show that the Christian ideals are not out of reach, but within our grasp.

Michael Kelly

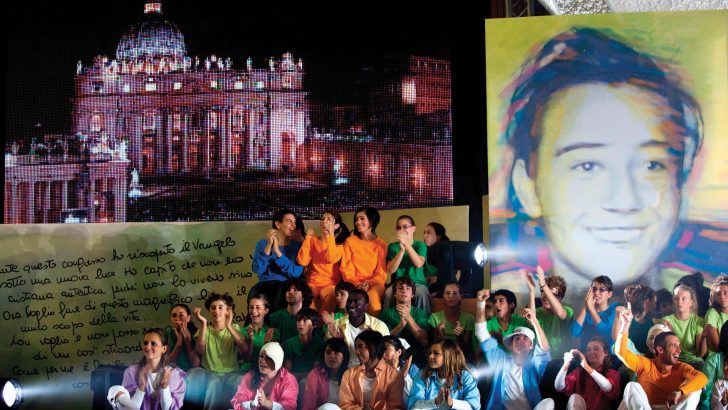

Michael Kelly An evening for young people and Focolare members in Paul VI audience hall to

celebrate the beatification of Chiara Luce Badano on September 25, 2010

Photo: CNS

An evening for young people and Focolare members in Paul VI audience hall to

celebrate the beatification of Chiara Luce Badano on September 25, 2010

Photo: CNS