100 Years On…

As the Great War drew to a close, this paper looked to what the future might hold, writes Gabriel Doherty

‘Is peace imminent?’ ‘German plenipotentiaries for armistice’ ‘Arrival at meeting place’

With such headlines in its edition of November 9, 1918, The Irish Catholic announced, for the benefit of those not already in possession of the information, that the final acts of the war were at that moment taking place in France.

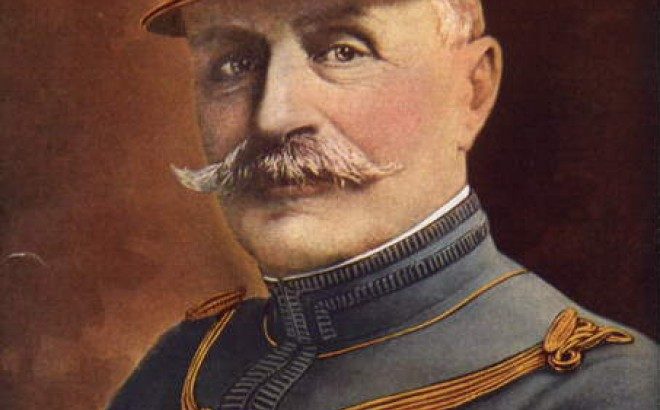

A high-powered German military delegation had passed through French lines, charged with the task of concluding a halt to the fighting, and had already commenced the necessary discussions with Marshal Foch and his subordinates. The report was brief, almost as if its author could scarcely believe that the news was real, that the death and destruction was actually coming to an end.

In fact, even as this edition of the paper was being distributed around the country, further momentous developments were taking place (notably the abdication of the Kaiser, and the appointment of a Social Democrat as Chancellor) that hastened the calling of the ceasefire. Certainly, there was no sense of hyperbole in the observation that during that past week history had “been in the making with marvellous rapidity and with events of epoch-making importance”.

Decision

So what was to happen next? Well, for a start, a General Election was to be contested across the whole of the United Kingdom. This should have been held during the war but the decision had been taken to postpone same until the fighting was concluded.

The intervening years had seen several significant changes in electoral law, all of which seemed to point to a more authentically democratic future. Women, or at least certain categories of propertied women, had been granted the vote, and were now eligible to stand for, and sit in, parliament on the same basis as men – although which parliament was, as yet, a matter for the future.

Of more immediate interest to The Irish Catholic, and to many Catholic commentators, was the effect of extending the franchise to almost all adult males (with some variation in age, depending on whether the individual had served in the armed forces). As a result of such changes, there was certainty that organised labour would now occupy a far more central place in the political arena than heretofore – a development the paper welcomed as a “beneficent revolution”. Doubt existed, however, as to the type of ideology that would inform and direct this organisation.

The paper’s analysis of the situation was based on its repudiation of the ideas, and legacy, of the “soulless system of unrestrained competition” labelled the ‘Manchester’ school of political economy, which it deemed to have directed British economic policy for decades. This “evil system of the oppression of the poor” treated human beings “as if they were of no more – nay, as if they were of less – account than mere pieces of machinery”.

The paper was grateful such a system was deemed to have had its day, but was concerned lest an even more dangerous ideology take its place.

The most extreme was identified as the ‘Internationale’ brand of Utopian Socialism, which was associated with state-sponsored abolition of private property, and annexation of all capital. The editor consoled himself that while this type of radicalism, no doubt encouraged by the advent of Bolshevism to Russia, was then enjoying a certain vogue in Britain and on the continent of Europe, it had yet to command any meaningful support in Ireland – but he cautioned against any resting on laurels.

Adoption

He referred in particular to the recent adoption by the Irish Labour party and TUC of motions that supported the transfer to workers “of the ownership and control of the whole produce of their labour” and “to secure the democratic management and control of all industries and services…in the interest of the Nation and subject to the supreme authority of the National Government”.

When one added to this development, recent speeches eulogising Bolshevism and the flying of the red flag at the Mansion House, the editor discerned a “somewhat disquieting” pattern of events.

Rather than be alarmed, however, he was inclined to dismiss such “moral aberrations” as temporary dislocations of the natural social order, caused by the war and destined to disappear after its termination. Lest any doubt should exist on the matter he reiterated the Church’s teaching as expressed through Leo XIII’s great encyclical Rerum Novarum, with its emphasis on the mutual rights and duties of Capital and Labour, and the need for, and benefits to be derived from, their harmonisation.

He found a powerful ally in the Jesuit Fr Thomas A. Finlay, founder in whole or in part of several widely-read Catholic journals (notably the New Ireland Review, Studies, Messenger of the Sacred Heart, the Irish Monthly and the Irish Homestead) and, amongst other achievements, Professor of Political Economy at UCD. By this point Fr Finlay had already played a distinguished role for many years in Irish intellectual life and was to continue to do so for nearly three further decades after independence.

Freedom

More specifically the editor endorsed a recent address by him to the annual conference of the Catholic Truth Society, wherein great stress was laid upon the duty of both employer and employee to each other and to wider society, and that the freedom of both was “limited by the laws of Christian brotherhood”.

It was certainly a noble vision – how practicable in would be in the aftermath of a destructive war only time would tell.

Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Marshal Ferdinand Foch