The Restructuring of Irish Dioceses

edited by Eugene Duffy (Dominican Publications, €20.00 / £17.50)

This book, the publishers explain, “provides a timely and thought-provoking exploration of the challenges facing the Catholic Church. The boundaries of Ireland’s 26 dioceses, unchanged since the 12th century, no longer reflect the distribution of the Catholic population.”

But such demographic change is only part of the problem; also of importance surely is the changed nature of that “Catholic population”. The Irish nation is just not what it was in the days of St Malachy.

A friend of mine remarked humorously that if the uniting of parishes went on they would get so large one might as well make the parish priest a bishop.

It was surprising to find this wry comment echoed by Bernard of Clairivaux, that in Ireland “bishops …were multiplied at the whim of the metropolitan until one episcopal see was not satisfied with one bishop, but almost every single church had its own bishop.”

The term diocese comes from the civil administration of Rome and the Roman Empire, which in a sense the Catholic Church was taking over. As a manner of organisation it had no scriptural or apostolic sanction. It was merely the most convenient way of doing things: by adopting the local form of civil rule.

So today what the Church needs to find is a manner of effective administration that is most convenient to our day and age. But this it seems will not be an easy task to provide a model that will work globally given the divergences of cultures now living in the Church.

This collection of a dozen reflective essays has been brought together with an introduction by Eugene Duffy, a former academic and now Episcopal Vicar for Pastoral Renewal and Development in the Diocese of Achonry.

The book does not present solutions as such, but explorations of experiences of administrative change of various kinds, here and elsewhere in Europe, with the experiences of such changes in religious orders and in the missions.

All of these present insights on what drives change and what it has achieved, and could achieve. The pieces are intended to provide “food for thought” – taken literally – and as such are full of insights.

Most people identify with their parish; or for those who live on a boundary as this reviewer does, their parishes, with all their associations with the events of life and death.

The parish of Donnybrook was once in the 16th century a much larger entity. But as the population of Dublin grew over the following centuries it was divided into several new parishes. Sometimes these were for social reasons: such as the creation of City Quay into which the dockers and their families could be assigned, removing them from the pews of St Andrews in Westland Row where the wealthy Catholics of Merrion Square worshipped.

Now the process is being reversed. But applied to a diocese, if two or three are united the authority of the bishop is removed further from the actual people. So a new definition of both parish and diocese is needed.

In a passage in this book (p.156) Eamon Conway describes a visit to Cambodia where a Jesuit group was at work, one of whom was the parish priest for a fishing community. They drove down to the shore and he telephoned to make contact with someone to pick them.

“He could never be quite sure where his parish was, geographically speaking,” as sometimes the boats the people lived on were near the shore, at others miles away at sea. He had built a floating church and a floating school and followed them. Here was a redefinition of “parish” not as a static place, but as a living community of faith in a real way.

So valuable as all the sights of history and experience in the book are – the essay by Willie Walsh on the relation of the diocesan bishop and the Episcopal Conference is particularly interesting – what the Church would seem to need is a new sense of definition of what a parish and a diocese are, breaking with the imperial domination of the Roman Imperial past.

The food for thought these pages provide will need digesting, but also like all food eventually absorbed into building a better and healthier church body. Eugene Duffy’s collection needs not only to be widely read, but acted upon. Even if it means creating a “floating” community that is quite new.

Peter Costello

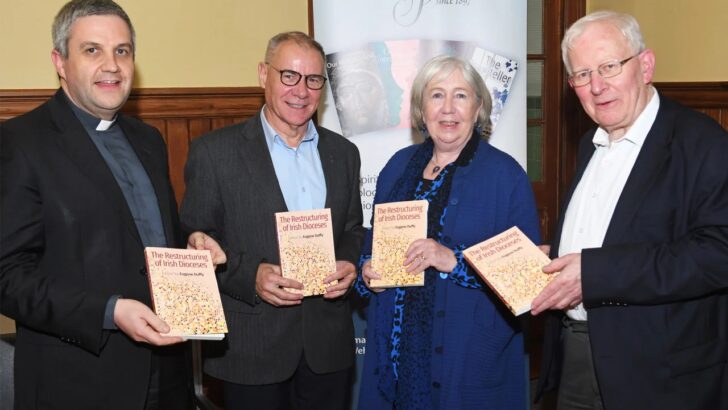

Peter Costello Author Eugene Duffy at launch of his book. Photo: Dominican Publications

Author Eugene Duffy at launch of his book. Photo: Dominican Publications