Martyrdom was a central – and complex – part of the Irish Reformation experience, writes Alan Ford

It’s hard to escape the tradition of political martyrdom in Ireland. The litany of names, from Wolfe Tone to Patrick Pearse to Bobby Sands, is commemorated annually at Bodenstown and on the gable ends of houses in the Falls Road. But the religious martyrs of Ireland are, surprisingly, less well known.

Martyrdom, of course, is a hallowed Christian tradition from the earliest days – “the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church” is the old cliché – with the various horrible deaths recorded in the extensive books of martyrs – the martyrologies. But in Ireland and England, unusually, the early Church was unpersecuted, leading to a severe shortage of martyrs.

It was not till the 16th-Century Reformation, and the fatal competition between Protestant and Catholic, that the martyr-count rose dramatically in the two countries. In England, Henry VIII and his daughter Elizabeth between them executed around 300 Catholics; Queen Mary put to death over 250 Protestants between 1553 and 1558. In Ireland lists of martyrs began to be compiled from the 1590s, as the toll of Catholic deaths at the hand of the English government rose during the sixteenth century’s rising tide of violence and persecution: in all, between 1529 and 1691 well over 260 martyrs are recorded.

The tragedy, of course, is that, unlike in the early Church where Christians were being killed by an uncomprehending Roman Empire, they were now being put to death by fellow Christians. “Truth purchaseth hatred,” as one contemporary English Catholic writer put it. The mutually conflicting truths of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation doubled the hatred.

Emperors

Though each side sought to preserve appearances by inisiting that those that they were executing were not martyrs, but heretics, blasphemers, or traitors, the horrifying reality was that Christians were once more being put to death for religion, just as in the days of the early Church, but this time not by pagan monsters such as Nero, but at the hands of emperors, monarchs and states who claimed to be Christian.

With terrifying logic, each side of the confessional divide claimed exclusive ownership of the title martyr. Catholic martyrs, as a result, now vied with their Protestant rivals to prove by their zeal and bravery the rectitude of their cause.

The deaths, often painful, gruesome and harrowing, can make for difficult reading. The most celebrated of the Elizabethan martyrs, Archbishop Dermot O’Hurley of Cashel, was arrested by the Dublin authorities in 1583. Suspected of being a Spanish agent, he was tortured by having his legs boiled in oil, till the flesh came away from the bones: he remained resolute. After a hurried trial by martial law, on 24 June 1584 he was executed on the gallows with a makeshift noose of bound twigs.

One of the few female martyrs, Margaret Ball (née Bermingham), was the widow of a Dublin Mayor, who was arrested on the orders of her Protestant son, and imprisoned in Dublin Castle for her Faith, where she died after three years in 1584. Of those recorded by contemporary martyrologists, most came from the south of Ireland, especially Munster, under a third were lay people, and of the clergy, most were from religious orders, with a particularly large number of Franciscans. Most of the recorded martyrdoms took place during the last three decades of the 16th Century and the 1640s and 1650s.

We tend to assume that the process of martyrdom is fairly straightward: godly martyrs are killed, their deaths are recorded, they are informally venerated, and in due course the Church formally beatifies them. But as with much of history, the facts of martyrdom can vary in the telling, often being intermingled with fiction.

Indeed, Candida Moss has recently shocked many people by arguing in her book The Myth of Persecution: how early Christians invented the story of martyrdom that many of the early martyr stories were pious exaggerations, even inventions. The accounts that have been religiously handed down from the early Church as history, as, indeed, moving and inspiring as examples of Christian fortitude, but they often strain the credulity of the unpious historian.

There is no doubt that the process of creating martyrs does intermingle narrative and history. John Foxe, who immmortalized the Marian martyrs in his best-selling Book of Martyrs, was both a good historian and a consummate story-teller. One Irish martyrologist, concerned at the lack of martyrs in his Trinitarian order and the shortage of recorded martyrs in Ireland during Henry VIII’s reign, even went so far as to invent a massacre of Trinitarians in Dublin in 1539.

It was only relatively late, in 1625, that the Papacy formalised the procedures for beatification – with an elaborate quasi-judicial inquiry or ‘process’ looking into the martyr’s or saint’s cause.

Martyrdom was of course a special case. For saints it was necessary to establish that the candidate had led a life of heroic virtue. But martyrdom was by its very nature more dramatic and less complicated – all was focused upon the heroic death. But the very ease with which it could be recognized created certain tensions between Church and people, as unofficial, local martyrs often gained wide followings without ever receiving official sanction.

This was what was happening in Ireland from the 1590s onwards, as a series of priests and bishops began to collect together accounts of the heroic death of Catholic clergy and laity, beginning with the Wexford Jesuit, John Howlin, who, around 1590 compiled a list of 46 Irish people who had died for the faith, and continuing with the Bishop of Down and Connor, Conor O’Devany who compiled a martyr’s index of bishops and priests who had died since 1585. These two works were expanded by David Rother, the Bishop of Ossory, who in 1619 published a list of 89 martyrs. Building on these works, the number of recorded Irish martyrs grew, and as the 17th Century progressed, they were increasingly incorporated into European Catholic martyrologies, particularly those of the religious orders.

As with political martyrs, religious martyrs provided an important rallying point for the faithful. In late 16th- and early 17th-Century Ireland, as the English crown established control for the first time over the whole country following a series of bloody wars, the previously antagonistic native Irish and Anglo-Norman populations were increasingly drawn together by their common religion and the idea of an Irish Catholic identity. The unofficial martyrologies reflected this new political reality, transforming what had previously been the random casualties of state violence into religious icons, symbols of faith and fatherland.

The martyrs became a battleground, as the Protestant state sought to portray them as traitors to the monarch, agents of foreign powers, stirring up unrest and participating in rebellion, whilst the Church emphasised their purely spiritual aims, seeking to bring pastoral and sacramental comfort to the persecuted Catholics of Ireland.

The way in which the public theatre of martyrdom could bring together the Irish Catholic people was most evident in the execution of the aged Franciscan bishop, Conor O’Devany. Accused of treason because of his association with Hugh O’Neill, he was sentenced to be hung drawn and quartered in 1612. As O’Devany went through the streets of Dublin to his execution sympathetic crowds gathered – “such a multitude as the like was never seen before at any execution about Dublin”, according to one chronicler – going down on their knees as he passed.

Even a hostile Protestant observer, Barnaby Rich, had to acknowledge the pious fervour:

“The execution had no sooner taken off the bishop’s head but the townsmen of Dublin began to flock about him… some cut away all the hair from the head, which they preserved for a relic; some others gave practice to steal the head away…

“Now when he began to quarter the body, the women thronged about him, and happy was she that could get but her handkerchief dipped in the blood of the traitor; and the body being dissevered into four quarters, they neither left finger or toe, but they cut them off and carried them away… and some others who could get no holy monuments that appertained to his person, with their knives they shaved off chips from the hallowed gallows; neither could they omit the halter with which he was hanged, but it was rescued for holy uses.”

In short, by the second decade of the 17th Century, the cult of martyrdom was fully established in Dublin. The execution of a native Irish bishop was able to attract a large and sympathetic crowd in the very centre of the English presence in Ireland. The popular response, the way the fama martyrii spread throughout Ireland, and the publicity accorded to O’Devany’s death across Europe, meant that the official efforts to define Catholic martyrs as traitors had failed.

It was not till the wars of the 1640s and the arrival of Cromwell that religious persecution and martyrdom resumed on a large scale, with a further 126 deaths being recorded by the martyrologists. The final Irish Catholic martyrdoms by Protestant hands occurred in 1691, preceded by perhaps the most famous martyr of all, in 1681, Archbishop Oliver Plunkett of Armagh, an innocent victim of the Popish Plot.

Despite the efforts of Rothe and his fellow martyrologists, the cause for the Irish martyrs never got under way at Rome, possibly for fear of exacerbating the position of Irish Catholics by offending the British government. It was not till the resurgence in Catholic confidence in the 19th Century, following emancipation in 1829, that interest grew once again in the fate of early modern Irish martyrs.

Cardinal Cullen and that formidable historian, Cardinal Moran, took up the case. A Jesuit, Denis Murphy, was put in compiling the evidence for the martyrs’ cause, and in 1896 published Our martyrs: a record of those who suffered for the Catholic faith under the penal laws in Ireland giving details of 264 individual martyrdoms, along with massacres of groups of martyrs, dating from 1535 to 1691.

With the support of Archbishop William Walsh of Dublin, work continued into the early decades of the 20th Century, and in 1917 formal approval was given by Rome for the introduction of the causes of 260 Irish martyrs.

The speed with which this cause proceeded was, however, very slow. The obvious contrast is with that of the English Catholic martyrs. As early as the reign of Pope Gregory XIII (1572-85) 63 English martyrs were informally recognised, though they were not formally beatified till the late 20th Century. Pope Pius XI beatified a further 108 English martyrs in 1929. In 1970 Pope Paul VI made 40 English and Welsh martyrs saints, and in 1987 Pope John Paul II beatified a further 85.

By contrast it was not till 1920 that Oliver Plunket was beatified, and not till 1975 that he was canonised, the first new Irish saint for over 700 years. And it was only in 1992 that 17 Irish early-modern martyrs were beatified, including Dermot O’Hurley, Margaret Ball, and Conor O’Devany.

Part of the reason for the delay in promoting the cause of the Irish martyrs was the complexity of their cases, and the shortage of resources to conduct the necessary historical research. In the complex politics of early-modern Ireland, distinguishing between political and religious deaths was often difficult, and in the case of some of those recorded by the early martyrologists, such as the Earl of Desmond, religious motivation was not always clear.

It was not till 1975, when Archbishop Dermot Ryan established a Diocesan Commission for Causes, led by the two leading historians, Patrick Corish and Benignus Millett, that substantial progress was made. The Commission selected 12 causes, which included 17 individuals, as a representative sample, including bishops, clergy – secular and regular – and lay people, male and female. The case was submitted in 1988 and approved in 1991, with the 17 Irish martyrs being beatified by Pope John Paul II in St Peter’s Square on 27 September 1992.

The Irish martyrs had finally been officially recognised and acknowledged.

Prof. Alan Ford is Professor Emeritus of Theology at the University of Nottingham.

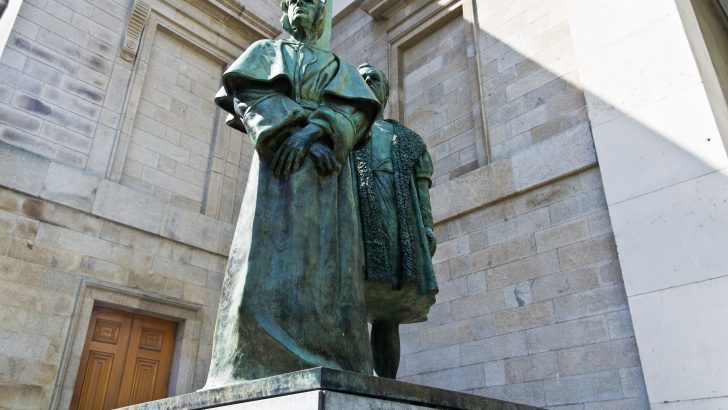

Statues outside St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral of the Dublin Martyrs, Mayor Francis Taylor and his grandmother-in-law Mayoress Margaret Ball, both of whom were beatified by St John Paul II in 1992 as part of a representative group of martyrs from the 16th and 17th Centuries. Photo: William Murphy

Statues outside St. Mary's Pro-Cathedral of the Dublin Martyrs, Mayor Francis Taylor and his grandmother-in-law Mayoress Margaret Ball, both of whom were beatified by St John Paul II in 1992 as part of a representative group of martyrs from the 16th and 17th Centuries. Photo: William Murphy