Tim O’Sullivan

Pour L’Église: Ce que le monde lui doit (“On Behalf of the Church: What the World Owes to Her”), by Christophe Dickès. (Perrin, €16.00); can be purchased directly on-line from Chapitre.com.)

In a letter last November, Pope Francis called for a renewal of the study of Church history. In this stimulating book, Christophe Dickès, a noted French historian and journalist, makes a similar point. He suggests that there is a need for a balanced look at the history of the Catholic Church and its legacy.

While acknowledging the grave scandals afflicting the Church today, he maintains that we who live today can act like judges of past generations, sometimes in an anachronistic way. He argues that we need to recover a sense of the complexity of the past and of the hugely positive contribution of the Church over time to the world in which we live.

There are some parallels to be drawn with Dominion by the British author, Tom Holland, which also examined how Christianity shaped the modern world. Dickès himself has produced several other books, including a Dictionary of the Vatican and of the Holy See, and he presents, on KTO, the French Catholic TV station, a respected history programme on the Church and Christianity. He is the author, too, of an historical book on St Peter, which has aroused great interest.

Themes

In this book, three overarching themes look at the Church’s contribution to societies, to politics and to humanism while there are individual chapters on attitudes to time, on education, on health and social care, on science, on laicité and religious-secular distinctions, on the Christian legacy of Europe, on the conception of a ‘just war’, on international law and the rights of native peoples, on the place of women and on the importance of conscience.

For space reasons, the author decided not to examine the enormous contribution of Christianity to the arts or to philosophy. The book is both learned and accessible, wide-ranging and relatively short so coverage of some topics is necessarily of an overview nature.

A fascinating first chapter argues that our conceptions of time are of Christian origin and can be traced, for example, to the pioneering work of Christian monks in institutionalising the ‘hours’ of the day. The author also refers to Pope Gregory XIII’s reform of the calendar, which still applies today.

Dickès also sets out the immense service provided by the Church across the world and across the centuries in healthcare and education. For example, in 2021, the universal Church ran 150,000 primary and secondary schools and over 5000 hospitals as well as thousands of other services in both education and healthcare. The author argues that the Church ‘schooled’ Europe and the world and that hospitals under various names were an invention of ancient and then of medieval Christianity, with a huge involvement of female personnel.

In the scientific arena, he argues that the heritage of the Church in the transmission of science has been downplayed. Though there were mis-steps, Christians overall believed in a Creator who had inscribed his laws in nature and had created a quantifiable and measurable world. Some Popes themselves had strong scientific interests – thus, Pope Sylvester II was a learned mathematician.

In the period between the Renaissance and the French Revolution. Rome itself was an important centre for the circulation of ideas and for multilingual printing, and this contributed greatly to the spread of knowledge. Moreover, the first scientific academy was founded in Rome in 1603.

The author does not seek to downplay darker moments in Church history, but he contends that Church leaders are sometimes not as attentive as they ought to be to long-term Church history and that today’s crisis of the Church is linked in part to ignorance of its history. In rejecting her history, he argues, the Church can become chained to present crises, but a Christianity which no longer believes in itself, or loves its history, is destined to disappear, just as paganism disappeared at the end of the Roman Empire.

Positive

However, the book finishes on a more positive note. Dickès quotes the French Dominican writer, Yves Congar OP, to the effect that the Church needs to have eyes in front and behind. Today’s Christians have received a rich heritage which they are required to transmit. There is a need to avoid both the negationism of ‘cancel culture’ and nostalgic, rose-tinted perspectives on the past.

Dickès argues that we need instead to draw upon the resources of the past while finding ways to be innovative in the present. History itself, he concludes, is a source of hope and reminds us of what we owe to past generations, and of their creativity, and of our own freedom in each generation to choose the path ahead.

Dickès is an expert on media copyright, and it is understood that an English version of his important book will appear in due course.

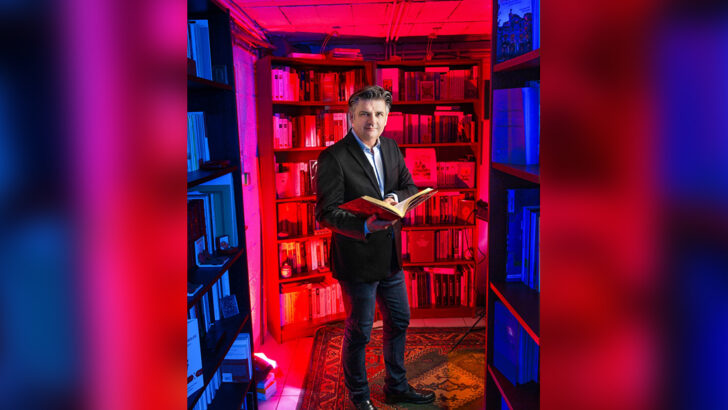

Christophe Dickès, noted Catholic author and television commentator.

Christophe Dickès, noted Catholic author and television commentator.