Digging Up Armageddon: The Search for the Lost City of Solomon

by Eric H. Cline (Princeton University Press, £30.00/$35.00)

‘Armageddon’ is a word that puts the fear of God in many people today. It is all very well having fears about the end of the world, the now fashionable ‘End Times’, when one is 12 – those came of reading too much about St Malachi and Nostradamus. But today especially among Evangelicals, Bible Christians, and some very traditional Catholics, end time prophesy has made talk of Armageddon’s looming proximity a commonplace for some.

Yet all of this modern anxiety depends, not on the Old Testament, or even very much on the New Testament. These fears derive from a passage in Apocalypse / Revelations XVI:16. Now the visions of John of Patmos are documents notoriously difficult to interpret, and over even recent times the identity of , say, the Anti-Christ has shifted from Napoleon, to Napoleon III, to the Kaiser, then to Hitler, and later to others.

Understandably there were many early Chrstians, when the canon of the Bible was being confirmed, who felt the Apocalypse/Revelations should be rejected as canonical.

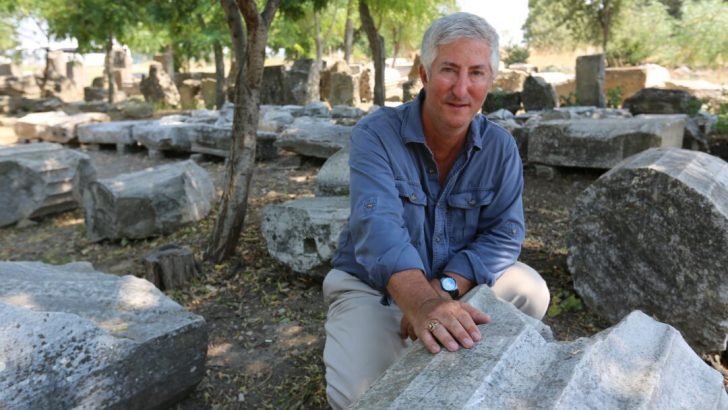

The site of that last battle between good and evil at Armageddon had usually been identified with the Tel Megiddo, now in Israel. In this new book leading American archaeologist Eric H. Cline relates the efforts of archaeologists, mainly from the Chicago Oriental Institute to excavate the mound layer one layer at a time in search of a supposed the ‘city of Solomon’.

Since the middle of the 19th Century many have hoped that archaeology as it developed as a discipline would ‘confirm the Bible’. But today we have learnt to wary of such a simplistic outlook, and conflicting, indeed discordant, theories about the Biblical people and places have developed.

This book is, for anyone interested in how archaeology is done, a fascinating read. It reveals from well documented archives at Chicago Oriental Institute what other writers had passed over in silence. Sir Leonard Woolley, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Geoffrey Bobby, C.W. Ceram all wished to present archaeology in the light of science rather than personal rivalry. But this book casts a spotlight on the psychology of the of the archaeologist themselves and the institutions they worked with, and in a detail which I suspect would dismay have such earlier giants of popular writing about the subject.

So detailed is his account of those involved that the book reads better than many a modern novel. It is truly and exciting read.

Armageddon resonated with so many people in America that it was thought it would attract newspaper attention”

The idea of excavating the hill of Megiddo came from the famous James H. Breasted. The name Armageddon resonated with so many people in America that it was thought it would attract newspaper attention, and make for good publicity for the Oriental Institute in an area dominated by the British, Germans and French.

The first great claim that the team had uncovered ‘the stables of Solomon’ helped raise funds as well as the popular profile of archaeology. Would it have been that easy: it is now thought the stables were not stables and did not belong to the time of Solomon.

The dig was well in hand when it came as a surprise to Chicago to discover that they had been paying rent to a local leader who had no right to it.

A large part of the hill belonged to a Mrs Rosamond Templeton, a eccentric British widow with curious beliefs.

Comment

Cline mentions but with no close comment that she was the granddaughter of Robert Dale Owen, a name one well known to students of fringe religions and mystical movements from the 1840s onwards for a century; here we are most certainly navigating the wilder shores of theology and Biblical prophecy.

But this aspect of the prophetic role of Armageddon is one which Cline passes over in silence. And rightly so, as it does not belong to archaeology but it has more to do with the social and psychological history of religion in modern times that with archaeology and Biblical scholarship.

The mystico-social history of Armageddon remains to be written. But in the meantime this splendid book will enthral anyone at all concerned with Biblical archaeology and its controversies. It is not exactly a sensational read, but is certainly a deeply human one, which great many more readers than its publishers expect to will greatly enjoy.

At the Tel Megiddo the work still goes on, lead now by local archaeologists such as Israel Finkelstein. Solomon’s city has still not been uncovered, but the end of the research is still nowhere in sight.

But with Armageddon less a pressing burden now than it once was, there is time enough to get to the bottom of the hill. The work, like all work of investigation anywhere, still goes on.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello Eric H. Cline

Eric H. Cline