Felix M. Larkin

Ireland’s Allies: America and the 1916 Rising

edited by Miriam Nyhan Gray (UCD Press, €40.00)

In August 1886, speaking at a gathering of Irish-Americans in Chicago, Michael Davitt said: “It is very easy to establish an Irish republic by patriotic speeches delivered three thousand miles away, but we could not do it on the hills and plains of Ireland.”

Not for the first, or last, time were Irish-Americans pushing Irish nationalists to act in ways that seemed imprudent and too extreme to those at the coalface at home.

But the 1916 Rising and its aftermath were to prove Davitt wrong.

A substantial measure of Irish freedom was won “on the hills and plains of Ireland” 35 years later – albeit after much loss of life and at the price of partitioning the island of Ireland.

The underlying thesis of this book is that the 1916 Rising was in large measure inspired and financed by Irish-Americans, especially the Irish diaspora in New York City – in other words, by precisely the kind of people whose revolutionary ardour Davitt had tried to restrain in 1886.

The eminent Irish historian, J.J. Lee – now based in Glucksman Ireland House, New York University – is thus quoted on the book’s dust jacket as follows: “No America, no New York, no Easter Rising. Simple as that.”

The book arises out of a conference held at Glucksman Ireland House in April 2016 to mark the centenary of the Easter Rising. The editor, Miriam Nyhan Grey, and the publisher, UCD Press, are to be commended on getting the volume out in record time – and for producing such a handsome volume.

Introduction

It comprises 24 separate chapters by a variety of scholars, both Irish and American – and, as stated by Nyhan Grey in her introduction, these chapters “provide an array of voices that help us understand what it meant to be interested in Ireland from the vantage point of New York circa 1916”.

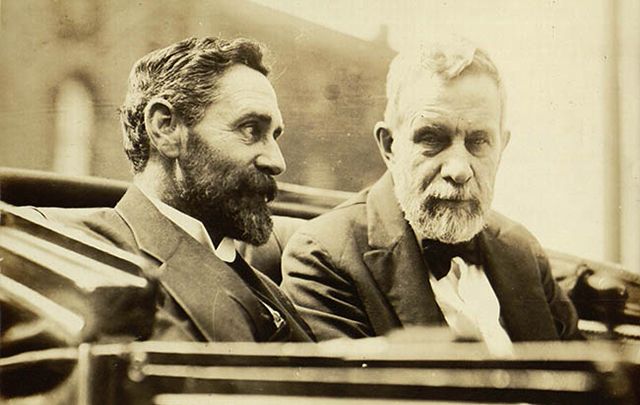

One of the strengths of the volume is that the chapters are linked by cross-references as appropriate, so that the volume has an overall coherence that is rarely found in essay collections. Another noteworthy feature is the well-chosen illustrations.

Most of the chapters focus on particular individuals, and these chapters fall into two categories. The first concerns leaders of the Rising who had visited the US and the influence that the US, and specifically Irish-America, had had on them.

Five of the seven signatories of the 1916 Proclamation spent time in the US, as did Casement – and indeed Tom Clarke was actually an American citizen.

Pearse was converted to “extreme republicanism” on his lecture tour of the US in early 1914 to raise funds for his school, St Enda’s.

The chapters in the second category are about influential Irish-American figures, most of whom were born in Ireland, but had settled in America.

Many of them are now largely forgotten. John Devoy is the best known, but among those also profiled in this book are O’Donovan Rossa’s wife, Joseph McGarrity, Judge Daniel Cohalan, John Quinn, Bourke Cockran, and Cardinal John Farley of New York.

The chapter on Cardinal Farley is complemented by a fascinating chapter on the attitude of the Catholic press in America towards the Rising.

Whatever about the response of rank-and-file Catholics, it is clear from these two chapters that the Church establishment was careful not to risk its position of growing respectability within American society by over-zealous support of those who had rebelled against America’s staunchest ally when that ally was engaged in a desperate war – even though America in 1916 had not yet entered the war. America would never be Ireland’s ally against Britain, and to that extent the title of the volume is somewhat misleading.

Tendency

There are also valuable chapters on the decline of Irish-American support for the Home Rule movement – which, it is argued, was already evident before the Rising – and on the coverage of the Rising in the US press generally.

Inevitably, there was a tendency in the popular press in America to see the Rising through the prism of the American revolution – and the author of the relevant chapter, Robert Schmuhl of Notre Dame University, writes that “Americans in 1916 … heard echoes of their own past wafting across the Atlantic”.

One omission from this otherwise comprehensive volume is any analysis of Irish-American attitudes towards Ulster unionists.

Irish-America indulged in ritualistic condemnations of unionist obstruction of Home Rule and of the prospect of partition, but there is no evidence adduced in any of the chapters that Irish-America had any real understanding of the problem of Ulster – or any ideas about how to address it.

Oblivious

Irish-Americans were oblivious to the irony that the unionists whom they regarded as interlopers on the island of Ireland had been here for about as long as European settlers had been in North America – and that the model of ‘liberty’ that the Irish had imbibed in America was not one that would be celebrated by Native Americans deprived, like the so-called ‘native Irish’, of their ancestral lands.