World of Books

Do Chrstians, and especially Catholic Christians, really understand and appreciate the true nature of Judaism today? I ask this question, which has some importance to the world today, because I have been looking into a book I casually acquired but which has turned out to be quite fascinating.

It is called A Treasury of Jewish Folklore (New York: Crown Publishers, 1948), edited with an introduction by Nathan Ausubel. It is a volume in a series from which I already owned the one on Irish folklore, compiled by no less a person than the poet and mythographer Padraic Colum. But this other book turned out to be very different from the Irish one, revealing indeed a quite different mental world to our own, now quite lost, folk outlook.

A Treasury of Jewish Folklore is a compilation of 750 stories and legends taken from the 2,000-year-old wisdom and traditions of the Jewish people, after the Diaspora. The book contains, as well, the words and music to 75 songs. It revealed a world, largely urban it has to be admitted, whereas Colum’s Irish one was totally rural – our folklorists believing, it seems, that people who lived in cities and spoke no Irish had no folklore at all.

So Ausubel’s approach to what he selected was very different to Colum’s, perhaps more revealing of a people’s true spirit. “Folklore is a true and unguarded portrait,” Ausubel claims, “for where art may be selective, may conceal, may gloss over defects and even prettify, folk art is always revealing, always truthful in the sense that it is spontaneous expression.”

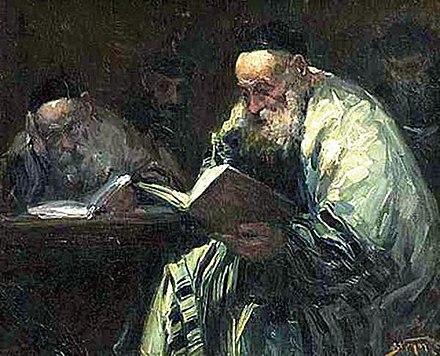

Though Christians are familiar with the Torah and the Prophets, they are quite unfamiliar with the Talmud and the Midrash, sacred wrings developed since the Diaspora. Of these later Rabbinic writings, Tolstoy remarked in the 1880s: “They contain something unendingly gentle and movingly great, like the rosy morning star in a quiet morning. The most precious quality in them is their agitation over the eternal mysteries of the human soul.”

For the Jewish people religion, life and learning formed a seamless web, from which was derived an outlook that was driven not by the fantastic as is so often the case with the Celt, but by hard one wisdom of people living in a close community, one surrounded by people who often rejected them. The Celt reveals in a glorious past, where as the Jew looks to the future, to ‘next year in Jerusalem’, as is prayed at Pesack.

Ausubel remarks in his introduction that: “Jews have received their tempering from an unflinching realism learned for a high fee in the school of life; they have always felt the need of fortifying their spirits with the armour of laughter against the barbs of the world.”

This book provides for the gentile reader an insight into the context from which sprang the writings not just the philosophers of the Jewish enlightenment in the early modern period, which was stultified to a great extent by the rise of Jewish Nationalism, but also the world of Scholem Asch, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and even Franz Kafka. Modern Jewish wisdom is a product of European experience, for better or worse.

Incomplete

Christians tend to think that Judaism is something incomplete. This is not the Jewish view; Jews see the promises of God as something still in the process of being unfolded and fulfilled.

Given the Christian idea that real Judaism ended with the Old Testament, it is understandable that they have not fully realised that Judaism today is the outcome of a two thousand years of history; it is as different from the days of David and Solomon and the prophets, as the Churches today are different from the simplicity of Jesus.

Just as Christian theology has changed and deepened the insights into revelation over two thousand years, so too Judaism has changed and matured.

The Orthodox Jews of modern Israel, whom many Christians see as the reality of Judaism, owe little to the Middle East in which Israel is set; in dress, custom, and belief they hark back to an 18th-Century Europe. In this they reject the developments of their own most sensitive teachers and leaders over the centuries. But then the same can be said of Catholics.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello adolf behrman

adolf behrman