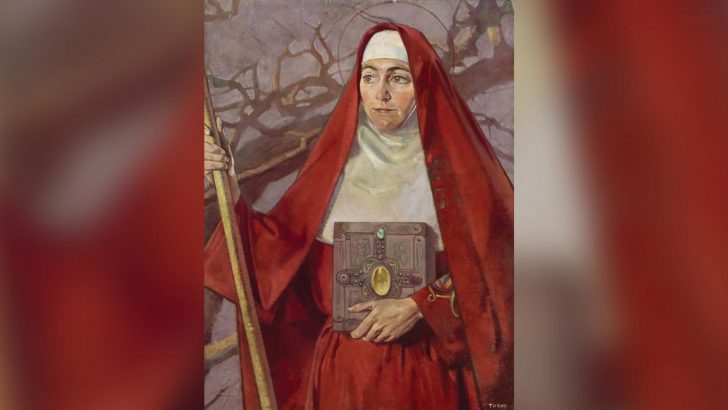

The Book of St Brigid

by Colm Keane and Una O’Hagan (Capel Island Press, €14.99/£15.00)

The names of the author will be well-known to readers, for many of their books have been popular bestsellers. They have a knack, derived perhaps from their days in television, of making what they write accessible, vivid and immediate to a wide audience.

Now the bulk of this book is devoted to legends and traditions of Brigid across the centuries, much of them from quite modern times and in North America. Indeed, in the popular lore of the United States all female Irish servants seem to have been called Brigid, though from reading popular fiction of the last century they were not considered to be as accomplished as Swedish cooks.

The authors have culled a great deal of amusing material about the connections of the name down to our own times. Though this strays far from St Brigid’s native Kildare it all makes for diverting reading.

But these traditions arose in Ireland and the central part of the book deals with the Brigidine connections in medieval and early modern time, in which the name of the saint was spread where ever the Irish went, into Wales, England, Scotland and across Europe over time. The saint’s name became so pervasive that they are able to connect up the Swedish St Birgitta (who flourished in the 1300s) with Brigitte Bardot, whose surprising Catholic connections are well drawn out by the authors.

Modern concerns

But what is most striking in a way for our modern concerns is the status in Gaelic pre-Norman Ireland of St Brigid herself. Like so many of Ireland’s early saints, she was a child of the ruling classes. Her establishment in Kildare was one of the most famous places in Ireland, as we can see in the admiring description that Gerald de Barri gives of it in his account of Ireland at the time of the Norman invasion after 1185.

What we know about Brigid has to be based on early Irish accounts of her life and their interpretation, which has often been mixed and contradictory (a familiar phenomenon in early Irish history).

The earliest of these, around 650, was by Cogitosus, who lived a century or so after the saint, and was familiar with her shrine at Kildare and the early traditions and legends then circulating about the saint and her numerous miracles.

But what many readers with a serious purpose will find of interest is the tradition that Brigid was ordained a bishop. This was called by one journalist in recent time a “grotesque fable”. But we are talking here of an early Celticised period of the Church in Ireland. She was made a bishop by Saint Mel. Another priest attempted to guide Mel by suggesting to him that a bishop’s orders should not be conferred on a woman.

To this admonishment Bishop Mel had a ready reply: “No power have I in this matter. The dignity has been given by God unto Brigit, beyond every [other women]”. The Book of Lismore (created at the end of the 15th Century) which only came into the hands of scholars in 1814, records that the men of Ireland would be obliged not only to regard Brigid as a bishop but that “Brigid’s successor” as Abbess of Kildare would also hold the title. But the reforms introduced by St Malachy and others especially after the Norman conquest changed the old Patrician ways of Christian Ireland to conform to the then current European norms.

Status

These days with increasing scholarly research into the status of woman in ministry in the first centuries of the new faith we shall surely hear more about the true status of St Brigid. These few pages form the controversial core of this book. And the serious nature of it should not be lost among all the entertaining and pious stories that fill the book and which make for interesting, even delightful reading.

But every book of a scholarly kind should have a list of books for further reading, but this book like so many these days – though it acknowledges its sources – does not have such a handy guide for the ordinary reader who wants to explore the subject further.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello St Brigid of Kildare

St Brigid of Kildare