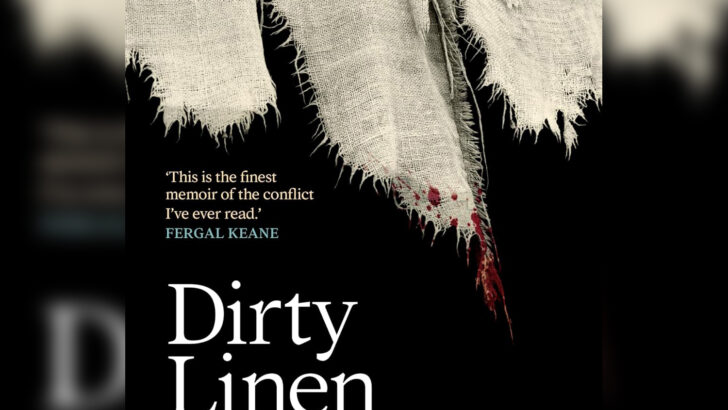

Dirty Linen: The Troubles in my Home Place, Martin Doyle (Merrion Press, £24.99).

Martin Doyle tells us in the introduction to this book that the Linen Triangle “stretched from Lisburn across the southern shore of Lough Neagh to Dungannon in Co. Tyrone and south to Newry, the heartland of a trade that was both agricultural and industrial and wove its way into the North’s identity”.

It is almost coterminous with the so-called Murder Triangle, the scene of some of the worst atrocities of the Troubles in Northern Ireland over a period of about 30 years. The ‘home place’ in the subtitle of Doyle’s book is the parish of Tullylish, Co. Down, which falls within these triangles.

Doyle’s focus is on lives lost and maimed through paramilitary violence in the few square miles of Tullylish parish, and his purpose is “to make it easier to understand what communities went through” during the Troubles. In other words, the particular will serve to illustrate the generality. He believes that “society would benefit … from a greater understanding and appreciation of the trauma that two generations endured” in Northern Ireland.

Trauma

He leaves us in no doubt about the trauma. In chapter after chapter, he disinters the toxic horror of the violence and counter-violence that infected his home place. He tells the stories of the victims – those who died and those who were maimed – and, perhaps more poignantly, the stories of those left behind to mourn their dead.

It was mostly violence by one community against the other – “bitter orange” against “green bile”, to quote one of Doyle’s many memorable phrases in this book.

Much of the violence he records was by loyalist paramilitaries against the nationalist community – his ‘tribe’ – and he explores the scandal of the involvement of members of the security forces in the loyalist gangs and the fact that a blind eye was turned to this by the authorities both in Belfast and in London despite widespread knowledge of it.

One aspect of the all-pervasive violence not covered by Doyle is that of the paramilitaries on both sides terrorising their own communities in order to enforce their unholy writ – in effect, a subaltern code or “subversive law” (the term used by the cultural historian, Heather Laird, in relation to an earlier period of Irish history, 1879-1920).

One of Doyle’s interviewees traces the beginnings of the descent into violence in Tullylish to “the vitriol of Ian Paisley preaching in the [local] Orange hall … in 1966”. The testimony of the person in question is that “Paisley brought hatred into the community. People were enraged with temper against us [nationalists and Catholics]. A lot of Protestant people held their common sense for a good number of years and still were friendly enough, but then when the IRA murdered cops, that done the harm [sic].”

Doyle himself is not in the business of assigning blame. His view is essentially that of Haines in Joyce’s Ulysses: “history is to blame”. In his introduction he refers to the Plantation of Ulster in the early 1600s which created “a divide that defines the region to this day”, and also to the massacre of Protestants by Ulster Catholics, under Sir Phelim O’Neill, in 1641.

He adds that “what was believed to have happened [in 1641] became more influential than what actually happened … Contemporary historians exaggerated atrocities and death tolls for propaganda purposes, to justify violent retribution.”

Regarding the wrongs inflicted on Protestants in 1641, Doyle quotes the father of the poet, Louis MacNiece – a Church of Ireland minister in Co. Antrim – as hoping that “we had the wisdom not only to remember but to forget”.

In a similar vein, the American journalist, David Rieff, has written memorably “in praise of forgetting” – arguing that a better understanding of the past does not necessarily facilitate forgiveness or reconciliation.

He suggests that “the price of remembering, at least in certain political circumstances and at certain social and political conjunctions, might still be too high”.

Fear

So, a fear I have about this book is that Doyle’s belief in “the power of storytelling and the healing power of nurturing, not neutering, the memories of loved ones we have lost” may be misplaced – at least in the public sphere. Memories can too easily be used to justify violence, both in the past and in the future.

In the conclusion to this book, Doyle pays heartfelt tribute to those who have had the courage to share their stories of pain and sorrow with him – and have thus enabled him to share their stories with us.

He notes that his experience in speaking with them has made him “even more intolerant of the apologists on all sides for the violent actions of their comrades – their moral casuistry, their ideological blinkers, their capacity for accommodating atrocity”.

Not for him the claim that there was no alternative to violence.