Frank Litton

Dorothy Day: The world will be saved by beauty, an intimate portrait of my grandmother

by Kate Hennessy (Scribner, $27.99)

Thérèse

by Dorothy Day, foreword by Robert Ellsberg (Christian Classics, Ave Maria Press, £12.99)

Cardinal Spellman (1889-1967) and Dorothy Day (1897-1980) were both important figures in the history of north American Catholicism in the 20th Century.

Both were based in New York. Spellman presided over the archdiocese from his residence on 5th Avenue; Day’s ‘House of Hospitality’ in Lower East Side gave shelter to the homeless and food to the hungry.

Spellman built up the infrastructure of the archdiocese. Just as importantly he established good relationships with the social, political and economic elite and brought the Church into the mainstream. His churches and schools promoted the Faith and taught charity and by winning the respect of the ‘great and the good’ he gave Catholics hope and confidence. He admired the military and was proud to serve as their ‘Head Chaplin’. He was a vigorous anti-Communist and supported the war in Vietnam.

Day and her colleagues saw a world profoundly marked by inequality and exploitation and in need of transformation. Catholic social teaching pointed to the direction. The first step was to give witness to the Gospels in the practice of charity. She was an unswerving pacifist throughout the Second World War and the Cold War. While Day had her admirers, and her followers, for much of her life she was a marginal figure working on the outside.

Canonisation

When Pope Francis addressed the joint meeting of the US Congress in 2015, he singled out two North American Catholics. One was Dorothy Day. In 1997 Spellman’s successor Cardinal O’Connor started the process for her canonisation. Thanks to her grand-daughter, Kate Hennessy, we now have an account of her life that will convince many that this is justified.

Day began writing a biography of St Thérèse of Lisieux in the early 1950s; it was published in 1960 and has just been reissued. As Day acknowledges in her introduction, it appears a strange choice of subject.

The worlds’ of Day and Thérèse could hardly be further apart. Day’s family were indifferent to religion, Thérèse’s were exceptionally pious. Day was reared in Chicago and lived most of her life in New York. Thérèse was reared in provincial France. Thérèse left the world for an enclosed Carmelite Convent at the age of 15. She belongs to the 19th Century; Day belongs to the 20th. She was engaged with the world as writer, editor and social activist.

The bohemian circles in which Day moved as a young adult had little or no time for religion. Yet Day had a religious instinct. This came strongly to the fore when her daughter Tamar was born. The transcendent became vivid in the wonder of new life. She insisted that Tamar be baptised in a Catholic Church. (She had observed that this was a church preferred by the poor.) This lead to a break-up with Tamar’s father that she tried hard to avoid. But he was implacable in his opposition to any and all religion.

She continued to write, publishing a novel and working, briefly, as scriptwriter in Hollywood. She returned to New York and while working for a radical socialist paper, she met Peter Maurin. His revolutionary version of Catholic Humanism showed her how her new-found faith could nourish and sustain her radical politics. She started the paper The Catholic Worker to promote Catholic social teaching and established the first “House of Hospitality” to demonstrate what it meant in practice.

Day’s biography of Thérèse introduces us to a saint with a succinct account of her family and life. When we read Hennessy it becomes quite clear why Day was attracted to her. St Thérèse encountered the divine, not in mighty deeds or profound thoughts, but in the particulars of daily life with their frustrations and promises. She lived in the presence of God.

Day brought the airy abstractions that faith, hope and charity often remain to many down to earth, back to the rough ground. She sought and found a transcendence few of us can find and from which all can learn.

She found it in the challenges of being a single mother while running a House of Hospitality whose residents were not vetted for character, personality or healthy habits. Funding was always a problem. Ambitions to establish farming communities were continuously frustrated and had to be abandoned. Articulating a position and finding a practice that did justice to her Gospel inspired vision of a just society was difficult.

Hennessy gives us a moving picture of the strengths and associated weaknesses of her personality and that of her daughter. She describes the force of circumstances that had to be overcome and the resources, religious and secular, she deployed. And all the time, we can discern the pull of grace and growth in faith, hope and charity. As with Thérèse, we learn where we should look to find our God.

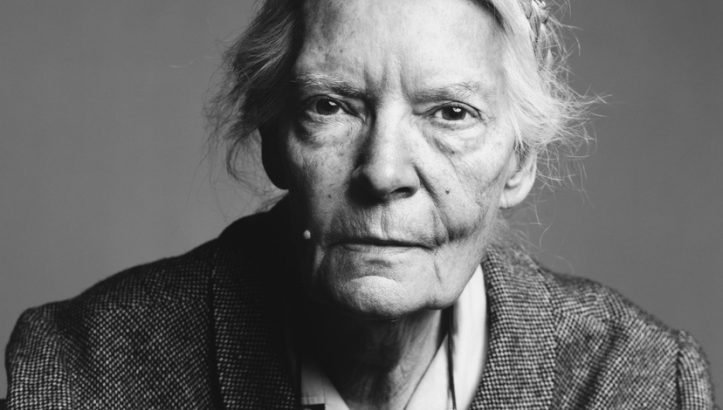

Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day