Mainly About Books

by the books editor

The other week in the course of a visit to Sligo, we spent part of a morning in Drumcliffe churchyard. We had been there before – what poetry lover in Ireland does not want to see the beautifully located grave of W.B. Yeats?

The church – which benefits from the donations of visitors – is dedicated to St Columba, and stands on the site of a monastery said to have been founded by the saint himself, and long connected with the royal sept of Donegal, who were his people. This would have been in the 6th Century.

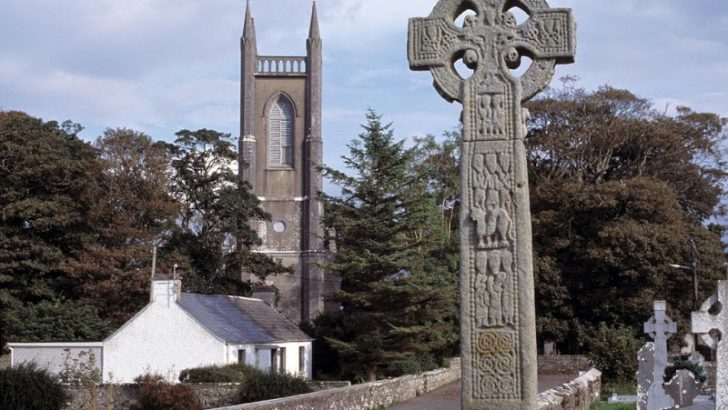

In the Catholic section of the graveyard there is a figured high cross. That great authority on medieval Irish art Françoise Henry remarks on its very individual style. The sculptures on the high cross include the usual scenes, such as Adam and Eve, the Crucifixion and so on. It dates from about 10th Century.

It was that high cross that produced the real surprise of the visit, something even more interesting than the Nobel Laureate’s grave.

According to the archaeo-logical notes on the plaque erected by the OPW, who look after our ancient monuments, one of the high relief images is that of a camel.

A camel, a veritable dromedary, in Drumcliffe churchyard? Surely not. How could such a beast, so typical of North Africa and the Middle East, be found in such an isolated place?

Perhaps we should not be quite so surprised. For the west of Ireland was not really so isolated as we often think. Drumcliffe is dedicated to St Columba. His biographer Adomnán wrote an account of the Christian shrines in the Holy Land.

Information

Adomnán got much of his information from a Frankish bishop called Arculf, who had personally visited Rome, Constantinople, Egypt and the Holy Land. On his return he was shipwrecked on Iona, where he related his travels to the saint. Arculf’s visit to the East was made in 670.

So at least some monks in early Christian Ireland were familiar with accounts of the Middle East, and would have heard something about camels. But there is more.

In an early medieval life of St John the Alms Giver, the Greek Orthodox patriarch of Alexandria in the first decade of the 7th Century, there is a passage which will surprise even some academics.

The writer relates that the saint sent a ship with a cargo of wheat to Cornwall. There its arrival helped avert a famine – climatic conditions seem to have taken dire downturn in those days. The wheat was exchanged for a cargo of tin, worked by the Cornish miners into the shape of dice or knuckle bones.

The ship had taken 12 days to reach the British Isles. Back again in Egypt the tin was sold for charity to raise money for the homeless and hungry of Alexandria. That passage of time, a mere 12 days, just twice as long a liner took in the middle of the last century on the regular crossings of the Atlantic, is what is surprising.

Over the course of the last two centuries many scholars and writers have commented on what must have been regular links between Ireland and Egypt. These were not new. Some blue faience beads found at Tara for instance show the links went back into the Bronze Age.

There are those who claim the early Irish Church was more Eastern than Roman”

The customs of the early Irish monasteries show the influence of the monastic traditions of the Egyptian deserts. Indeed the very word ‘desert’ (as in Dysart O’Dea) was introduced into Ireland as a term for a hermitage in the wilds.

Indeed, there are those who claim the early Irish Church was more Eastern than Roman, and that a distinct ‘Celtic Church’ only became fully Romanised at the time of St Malachy and the Anglo-Normans.

Recent scholars have been sceptical about this idea (perhaps rightly so) and some of the claims made about early Christianity in Ireland. But this curious carving makes one think.

Perhaps future visitors to Drumcliffe churchyard, having paid their respects at the grave of the poet, might pause to look at the humped backed creature on the high cross, before driving on to the Wild Atlantic Way along our western seaboard.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello