While many egregious past failings are highlighted the audits reveal real and substantial progress, writes David Quinn

Awaiting the release last week of the audits of child protection practice in six dioceses, the big question was whether they would reveal failings on the scale of Cloyne diocese.

That is, would they reveal failings that put children at risk during the time in office of the various incumbent bishops, or post-1996 which is when the first formal child protection policy was introduced by the Irish Church?

Thankfully, the answer to these questions appears to be, no.

A failure that puts a child at risk might be called a first order failing. Not telling the gardai¨ that a priest had been accused of abuse would be an example of a first order failing and would be a resigning matter.

The audits reveal many first order failings prior to 1996 and prior to the periods in office of the present incumbents. The six dioceses audited were Ardagh and Clonmacnois, Derry, Dromore, Kilmore, Raphoe and Tuam.

The audits, conducted by the Church’s National Board for Safeguarding Children, look at the handling of abuse complaints from January 1975 down almost to the present.

Most of that time covers the period prior to the present bishops taking up office and prior to the introduction of the 1996 child protection guidelines.

The audits are not remotely as comprehensive as the statutory investigations into Dublin or Ferns or Cloyne, which each ran to hundreds of pages and dealt in great details with how a sample of allegations were dealt with.

Some victims were disappointed that the six audits did not go into the same level of detail. But this could only have happened if the board spent a very great deal of time investigating each diocese.

However, the main priority of the board in conducting these audits was not to investigate the past, but to find out what is happening in the present, that is to find out whether children are being properly protected right now.

More time spent investigating the past would obviously mean less time investigating the present and given the urgency of ascertaining whether other dioceses were guilty of Cloyne-style failings, investigating the present had to have priority.

As mentioned, while the audits reveal very serious first order failings in the past, it would appear that none of the present bishops were guilty of such a failing.

However, it is important to emphasise the words ‘it would appear’. We cannot be absolutely certain, and the board cannot be absolutely certain that it has all relevant information.

Perhaps in the future some piece of information will come to light that reveals a first order failing in one of the dioceses within the period of office of a present incumbent.

That caveat aside, the audits reveal second order failings as distinct from first ordering failings by some of the present bishops.

Support

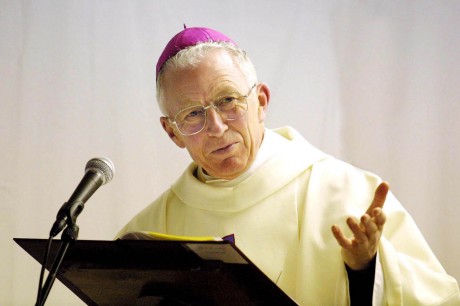

For example, Bishop Philip Boyce of Raphoe acknowledges that in certain instances more pastoral support should have been offered to complainants who had made abuse allegations against priests.

The audits also reveal certain failings on the part of the civil authorities. The audit of Tuam archdiocese finds that sometimes when an allegation was passed on to the gardai, ”they took little or no action, with the result that the archdiocese was required to carry out its own investigations”.

In addition, it was discovered that gardai¨ in the archdiocese were not referring allegations to the HSE as was required by a protocol between the gardai¨ and the HSE.

It should be noted that certain bishops win high praise from the board. One is Dr Michael Neary, Archbishop of Tuam.

The audit finds that since he became archbishop in 1995, Tuam has passed on all allegations of child abuse to An Garda Siochana.

It says: ”The records demonstrate that since the installation of Archbishop Neary the archdiocese has met allegations with a steadily serious approach, taking appropriate action under existing guidelines.”

Similarly, Kilmore diocese under Bishop Leo O’Reilly is described as ”a model of best practice”.

Good child protection guidelines do not simply involve telling the civil authorities about every abuse allegation made against every priest. They also involve ensuring that no child is abused in the first place.

They involve ensuring that the person making the allegation is dealt with sensitively. They involve ensuring that the right of the priest to his good name is properly protected.

Difficult task

They place upon the diocese the very difficult task of deciding whether a priest who has been investigated by the civil authorities and cleared for lack of evidence, should nonetheless be kept out of ministry because the diocese judges he is probably guilty anyway.

But if the man is actually innocent, a great wrong will have been done to him. On the other hand, if the diocese puts him back in ministry because the civil authorities have cleared him, and he is really guilty, then he might abuse again.

To finish on a more upbeat note, what the six audits show is that the Church is finally starting to get things right regarding child protection, and in some instances it has been getting it right since the mid-1990s, that is for the last 15 years.

What they also show is that other bishops aside from Archbishop Martin have a very good track record on this issue and that it is unacceptable to constantly compare all the other bishops unfavourably with Archbishop Martin in this respect.

The ‘bishops’ are not a monolith to be held collectively guilty of child protection failings aside from Dr Martin. That may have been true to varying degrees prior to the mid-1990s but it is not true now.

Instead the bishops are a group of individuals who must at this stage be assessed individually. By the time all of the audits are completed, hopefully we will know exactly which other bishops can join the likes of Diarmuid Martin, Leo O’Reilly and Michael Neary in being able to look the public in the eye when talking about child protection.