The gothic cathedrals of Europe are recognised as one of the glories of European art. Every year hundreds of thousands, in some cases even millions, visit such places as Notre Dame de Paris, Amiens, and Chartres – indeed the great rose window of Chartres is one of the wonders of human ingenuity in praise of God that are for many a “once in a life time’s” experience, rather akin (in my experience anyway) to my first sight of the walls of Carcassonne.

I could not believe that such a complete city of the middle ages could have had survived in such a way – and indeed it had not. The hand of the great Eugene Viollet le Duc had passed over it, as it had also passed over Notre Dame and many other places, ensuring that the relics of Europe’s past survived into an age more heedless of faith.

Significant

Yet one of the most significant places in the development of gothic architecture is largely unvisited, not because it is difficult to get to (like St Bertrand de Comminges in the Pyrenees). No, the abbey church of St Denis, the shrine of the Patron saint of France, Paris and the French monarchy, dating back to Third Century it is thought, over which was erected a great basilica in Sixth Century, can easily be reached by a short bus or train ride, for the march of time and history has left this once famous place stranded in a neglected industrial suburb of north Paris.

The place had been given a bad name since Victorian times: Augustus Hare remarked that “the way to St Denis lies through a manufacturing suburbs of Paris, and is very ugly” (Days near Paris, London 1875, page 161).

But what there was to see then was very different from the basilica in its days of glory.

In 1790 the anti-clerical Republican revolutionaries passed a decree closing all religious establishments. A mob descended on the basilica and tore out the royal tombs and broke them up, the building was unroofed and left to decay.

In 1800 Chateaubriand wrote a vivid account of a visit there. However the fragments were gathered up through the energy of a single individual and placed in a museum. Later, when the thrilling days of revolution passed into decades of bourgeois respectability, an effort was made to restore the tombs. These can be seen today, but often the tour is rushed, so that only a vague impression can be gathered of the place.

However, the shattered history and now neglected basilica has an important place in architectural history. In summary, the church was built in 475, and later reconstructed by Dagobert. This church was replaced in the middle of the Eighth Century. Given the later changes, of his actual work only the west porch, one tower, and the apse of about 1144 survive.

The work of the Abbé Suger initiated the Gothic style. In later centuries his work was, as noted, changed as well, and the development from Romanesque can be followed in the changes made in the basilica over the centuries, though not in all details. The restoration under Napoleon I was deemed to be in bad taste, but during the reign of Napoleon III, Viollet le Duc was entrusted with the further restoration and under his hand the basilica “regained much of its ancient magnificence” (Karl Baedeker, Handbook to Paris, 1894, page 325).

Exploration

The Basilica of St Denis, despite the vicissitudes of its history, is the ideal place to begin an extended exploration of gothic architecture and the religious outlook of the middle ages in Europe. The style, many think, was the initiation too of that change of feeling from the classical Romanesque of the Mediterranean, replacing the brick and tiles of the south, with the soaring style in wood and stone of the north.

The change of mood was perhaps the earliest impulse towards the Reformation and then the Counter Reformation; a sort of premature ‘break with Rome’. (Here in Ireland the gothic is associated with the Church of Ireland, the classical with the Catholic Church, so much so that Dr McQuaid seems to have considered the Romanesque basilica to be the only possible style for the huge churches he had built in the long years of his administration of the Catholic diocese of Dublin. He distrusted the gothic.)

It is often said that the names of builders of the cathedrals of Europe are unknown. This is true, but the initiators are often recorded, and their names have been passed down. The Abbé Suger is one of those. He was not, of course, the actual architect. He was the initiator. It is clear that he was a very remarkable man, a priest of an all-encompassing energy and effect, the kind of churchman quite unknown today.

***

But to return to the cathedral builders, the men responsible for St Denis, Notre Dame and Amiens; their names often unknown, but what they did and how they might have gone about it are very fully recorded in illustrations, drawings and illuminations. And these scenes in their activity have their own special interest.

Another kind of exploration of Europe might also be commenced at St Denis. Its great fame was as the necropolis of the kings of France since the time of Dagobert (who died in January 639). But it is not the only such place in Europe.

Next door to us, Westminster in London has been a place of royal association since the time of the Anglo-Saxons kings. In time it came also be the place where the great and the good were buried, even Charles Darwin found a place here (but not Thomas Huxley his advocate; but then Darwin had once aspired not to be a naturalist, but an Anglican priest.)

On a visit to Denmark some years ago my wife and I took the trouble to visit Roskilde in the heart of East Zealand. This has a direct link with Dublin for in the Viking boats in the inlet of the sea on which the city stands, were found the remains of a Norse ship made of Irish, perhaps, in fact, of Wicklow wood. But other kinds of boats and ships can also be seen in the Roskilde ship museum as well.

However, high on the bluff of the hill overlooking the harbour stands the gothic cathedral finished in 1275, where some 39 Danish monarchs are entombed. Their names are unfamiliar, as the more powerful nations of the continent, Britain, Germany and France, have now little interest in learning about the countries of Scandinavia.

There yet remains on our ‘must do’ list a visit to Vienna, and the Capuchin Crypt in which are laid up the remains of a long line of 150 Hapsburg Kings and Emperors, an extraordinary maze like series of vaults crammed with the tombs, a treasury of 400 years of religious art.

The Capuchin Crypt too has a link with Ireland, for here is the tomb too of the Empress Elizabeth, the wife of Emperor Franz Joseph, a horsewomen of skill who loved to pass a few months when she could, hunting in our midlands. She gifted Maynooth College with a set of wonderful vestments, which are still treasured by that much changed place and can be seen in the college museum. This misfortunate beauty was stabbed to death by an anarchist on the quayside of Genève in 1898, a forewarning of the political violence that has engulfed the continent ever since.

***

But to return to St Denis, and the origins of the gothic style. This was the creation, as some French historians say, of the genius of Abbé Suger (1080-1151), priest and statesman, very much in the medieval style. During the crusade of St Louis after 1248 he was the actual ruler of France.

It was here that Jeanne d’Arc offered up her arms and armour on the altar to God in 1429. Here Henri IV in 1593 renounced his Protestant faith, remarking (legend claims) that “Paris is worth a Mass”.

Here also in 1810 Napoleon I was married the Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria, a daughter of the Austrian Emperor; she was his second wife. Napoleon intended that his imperial line would be buried in St Denis, but this never came about.

Napoleon

It was Napoleon who began the reconstruction of the basilica, but it was taken to completion by Napoleon III in the middle of the century. He engaged Viollet le Duc to work on the shrine and other churches in the quarter. But with the creation of the Third Republic in 1870, the attraction of the place began to fail. The city centre of Paris had become the theatre of French history and not this industrial suburb.

Some years ago a parish priest of St Denis wrote an article for Le Monde about the difficulties of the shrine today, which had become run down and is inhabited by emigrants of many cultures with little interest in Christianity. Few others, either Parisians or tourists made their way to the basilica whether out of interest or respect. It was an article that made for sad reading.

***

The history of the gothic style is almost the history of modern Europe. There was in time a classical revival, followed by a gothic revival, and then a neo-gothic movement, which was eventually over taken by modernism.

What admirers of the continent’s gothic cathedrals overlook is the remarkable fact that when first erected they were painted; the raw stone was coloured. Today the effect is often achieved by son-et-lumiere effects. But no one has, I think, dared to restore a church to its original condition. It would be a remarkable sight if one were.

***

But aside from what they looked like when they were first built, that bright fresh stone work and smell of new wood, we all too often overlook just how they were built. However, through those illustrations, drawings and illuminations we have a remarkable record of the architects, masons and carpenters at work.

These like the images of rural life through the season to be seen in the Very Rich Hours of the Duc de Berry, which records in detail rural life in all its detail and charm in the middle ages. But the scenes of church building work are some of the liveliest medieval images we have.

Anyone like the Abbé Suger setting out to erect a cathedral had to take some import first steps. The first step of all, supposing the site, having been chosen for existing reasons of policy, was to secure a large, nearby and accessible source of stone.

After that, but almost equally important, was a supply of useable timber from a nearby forest. But timber has to be seasoned and cared for before it is used. This too takes time and money. Then when the edifice is complete it had to be decorated and fitted out, which demanded large supplies of fabric and tapestries for the hanging.

Then there was the highly skilled matter of creating and installing the stained glass windows. Visitors today are stunned by the Rose window at Chartes, or by the sheer glass wall of an interior like the Sainte Chapelle in central Paris. There the panels showing the saints rise up the roof.

Someone like myself whose sight is a little stunted has to wonder about the vision of the middle ages – they seem to have been able to apprehend small details at a distance and a height that eludes the modern eye. They also gave to the carving of the saints and figures from life, the angels of God and the saints, and also to strange and varied beasts, creatures and monsters of creation.

These details capture the imagination and engage our minds in way which very few modern churches (aside from creations like Gaudi’s in the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona.

The architecture of the middle ages, in all its details, all its vigour, its intellectual apprehension, its truth to nature, and deep religious fervour, is a life’s time engagement. It’s never too soon, or indeed too late, to start.

With acknowledgement, among other sources, to Quand les cathedrales étaient peintes, by Alain Erlande-Brandenberg (Decouvertes Gallimard, (c) Gallimard 1993).

Peter Costello

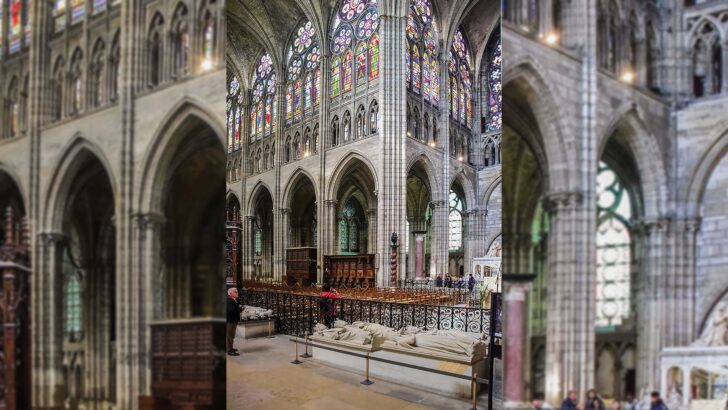

Peter Costello The trascept of the basilica of St Denis.

The trascept of the basilica of St Denis.