I Judge No One: A Political Life of Jesus by David Lloyd Dusenbury (Hurst Publishers, £25.00/€30.50)

Frank Litton

The horrible costs of the Ukrainian war in human lives and material destruction are agreed. One expert analysis reports that an estimated 180,000 Russian soldiers, 100,000 Ukrainian soldiers, plus 30,000 civilians have been killed, putting it in the top ten of the deadliest wars since 1812.

What we do disagree about is the context in which these facts belong. Some propose that Putin’s war, if not justifiable, is understandable as a response to United States’ aggression in attempting to push NATO forces right up against Russian borders. States do respond when they perceive their security is threatened. And the United States has a long history of military adventurism.

Support

Others point to Putin’s need to win support for his faltering regime with a narrative that extols Russia’s glorious past, laments its humiliation by western powers, and promises to restore it to its rightful place as a great power. The malign consequences of aggressive nationalism are a historical commonplace.

My purpose is neither to defend or attack either position. I mention the debate as a reminder of the vital role context plays in our understanding and to raise the question “what would we find if we placed the war in the context of the Gospels?”

David Lloyd Dusenbury helps us find an answer. Dusenbury is a philosopher and historian of ideas, whose books include The Innocence of Pontius Pilate (also published by Hurst). He currently holds a joint chair at the University of Antwerp’s Institute of Jewish Studies and University Centre Saint-Ignatius.

He does not address the question directly. As a historian of philosophy and a student of ancient history, he places the Gospels in their time and place and the history of philosophy. The passion and death of Jesus is cast in a fresh light where we can perceive its significance as a crucial moment in world cultural history.

We live out our lives playing the roles that society provides and culture scripts: mother, daughter, teacher, politician, lawyer, judge…. What role did Jesus play?

He was recognised by all as an exceptional teacher [Rabbi], and as prophet by others. Some later commentators counted him among the philosophers in the company of Pythagoras and Socrates who like him were “without honour in their own land”; Pythagoras and his followers were attacked and escaped into exile, Socrates was executed.

Some saw him as a zealot, fighting against Roman rule, disparaging him as a failure, a “terrorist” rightly executed. Later commentators have given his purported zealotry a positive reading, co-opting him into a Marxist narrative.

Placing him among the philosophers, Dusenbury observes, reveals his unique message; while they taught metaphysics and ethics, he taught forgiveness as he moved among sinners. Casting Jesus as a Zealot, a political activist, is a profound error he emphasises.

Tempted

When Jesus was tempted in the wilderness the temptation was triumph in the political game of power and domination. Jesus, as Dusenbury points out, was tempted again in the episode of the ‘woman caught in adultery’.

On this occasion the temptations were to engage in the business of Judean law and politics and cancel a statute of the sacred law given by Moses. Jesus resists, he does not judge, No one without sin steps forward to cast the first stone, the crowd melts away.

So Jesus refuses the political and legal roles that could so easily have been his. He was, of course, caught up in the legal and political machinations of others. Dusenbury is particularly helpful in guiding the reader through the complexities of the trials of Jesus, which has always been a difficult topic to untangle.

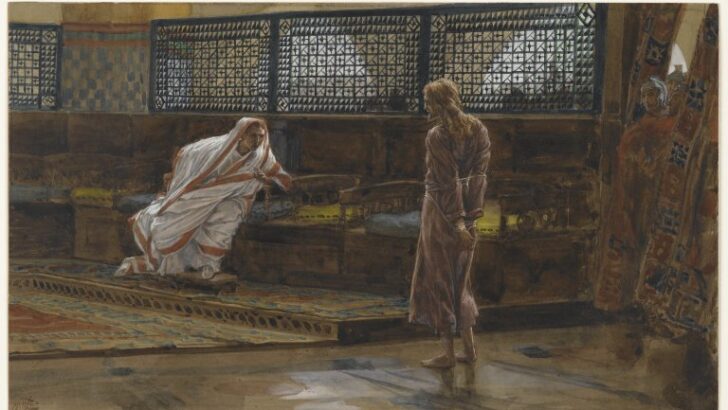

Jesus was accused of blasphemy before the Temple court before being brought before Pilate and charged with sedition. Both trials combined the political with the sacred. The Roman court was in no way secular as is sometimes supposed. The emperor was seen as a god, and sedition was as much an offence against the sacred, as was blasphemy.

In neither trial, did Jesus play the standard role of defendant, strenuously denying the charges and mustering evidence in his defence. So our attention is moved away from the drama of guilt or innocence, to the courts themselves and the political expediency and legal contrivance that drove them. Not for the first time, the combination condemned an innocent man to death. This time it is different. The mechanisms, once cloaked under “justice”, are exposed.

Jesus replies to Pilate. My kingdom is not of this world; if my kingdom were of this cosmos my subjects would have struggled so that I should not be handed over to the Judeans; but for now my kingdom is not from here.

A new perspective opens, the sacred is disentangled from the political, the idea of the secular enters history with enormous consequences. From now on the Christian is called on to see the ‘City of Man’ from their place in the ‘City of God’.

Not always an easy task as the Ukrainian war exemplifies. At the very least, I suppose we should refuse to see it as a melodrama, throwing our support behind the ‘good’ to defeat the ‘evil’. The war is evil, a tragedy, one more manifestation of human wickedness, one more reason to pray ‘thy kingdom come’.

Our sights should be on the human suffering, our efforts directed towards peace and not victory.

It is impossible in as short a review as this, to do justice to the depth and subtlety of Dusenbury’s analysis as he teases out the implications of the Gospels’ accounts of an innocent man crucified because he loved and did not judge. This book will challenge and transform your understanding of the interplay between politics and Christianity.

Jesus Before Pilate, the first interview, water colour by James Tissot (1886-1894).

Photo: Brooklyn Museum.

Jesus Before Pilate, the first interview, water colour by James Tissot (1886-1894).

Photo: Brooklyn Museum.