The View

Memories of people and travel, repeat performances and modern systems of communication with family, friends and colleagues all help to maintain sanity. While the airwaves are dominated by just one subject, we all need occupations that can absorb our attention and lift our mind onto other things.

The museum of the Vienna State Opera House provides a parable for the ending of the Second World War, the subject of muted 75th anniversary commemorations this month, and European recovery thereafter.

The last performance before the Vienna State Opera was bombed in the autumn of 1944 was fittingly Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, or ‘Twilight of the Gods’, the last of four operas based on the medieval sagas of the Nibelungenlied. Valhalla, home of the Norse gods, goes up in flames. Hitler was a great admirer of Wagner, who was markedly anti-semitic, and the Third Reich ended in similar immolation.

General von Choltitz defied Hitler’s orders to blow up Paris, when the Germans left in August 1944. Appeals were made by Eamon de Valera to all sides to spare Rome, as the allies advanced northwards from the south of Italy.

Spared

Vienna was fortunately largely spared as well. Russia, as successor of the Soviet Union, is proud of the particular care that was taken, when they captured Vienna, because of its importance as an historical pearl of western Europe.

Sparing cities also meant sparing its people, which did not happen in the case of Dresden, which was blanket bombed in February 1945 by the British and American air forces in an entirely gratuitous military punishment.

The city took decades to rebuild.

In 1955, Soviet forces withdrew from eastern Austria, including a sector in Vienna. It was also the year Ireland joined the United Nations, the Soviets having lifted their veto. While there are different views on the aesthetics of the large Soviet war memorial in the city, the Austrians have sensibly left it stand.

The rebuilt State Opera House reopened the same year, with a performance of Beethoven’s only opera Fidelio. It is in the heroic mould, and celebrates liberation from oppression and also marital faithfulness in its most pronounced form, where Leonore risks her life to rescue her unjustly imprisoned husband, who is about to be murdered.

Brahms once wrote on a card, on which was printed a few bars of Johann Strauss’ Blue Danube waltz, ‘alas, not by Johannes Brahms’”

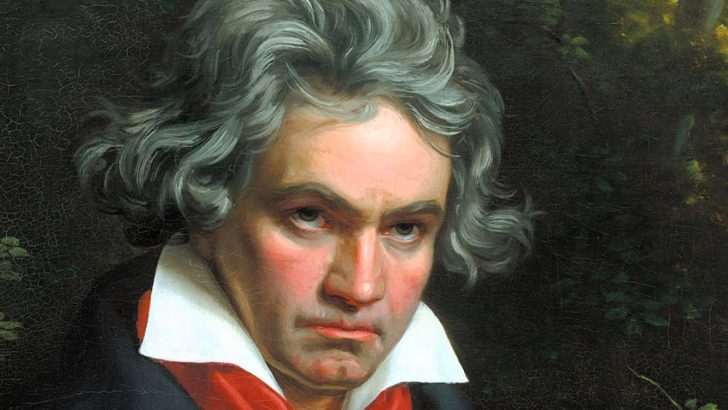

This is the 250th anniversary of the birth of Ludwig van Beethoven in 1770 in Bonn, a city that was part of the domains of the Archbishop Elector of Cologne. The handful of electors were so-called, because they elected the Holy Roman Emperor, who latterly was nearly always a Habsburg.

In his early 20s, Beethoven went to Vienna, where he spent the rest of his life, initially to study with Haydn.

It was a city that between its nobles and its diplomats contained great patrons of music, and was home then and since to many famous composers.

Beethoven is indisputably the greatest of all, taking together the best of his symphonies and concertos, his piano and cello sonatas and his string quartets. Brahms sometimes felt intimidated by his shadow.

Both Beethoven and Brahms also had to acknowledge the popularity of lighter music. Towards the end of his life, Beethoven met Rossini, and encouraged him to carry on, as Rossini was much more to the taste of the Viennese public in the Biedermeier era than he was. Rossini was so successful with his prolific operas that he was able to retire early, though in 1869 he composed a magnificently enjoyable petite messe solennelle, which was neither little nor overly solemn.

Brahms once wrote on a card, on which was printed a few bars of Johann Strauss’ Blue Danube waltz, “alas, not by Johannes Brahms”.

In 2014, Jan Swafford, an American composer, published an absorbing and compehensive critical account of the life and music of Beethoven sub-titled ‘Anguish and Triumph’.

Even though the book contains many musical quotations, it can be enjoyed by anyone interested in music history. Beethoven’s deafness was a huge physical handicap that he managed to transcend.

He had a prickly personality, and a difficult personal and family life.

His early career and the last stage of Haydn’s from 1795 to 1802 overlapped. One of the themes of the book is how Beethoven set out to surpass his world-famous teacher, who was mostly too busy to devote much time to his lessons, so that he had to take them elsewhere.

Desolation

Beethoven belonged more to the revolutionary and Napoleonic era, which JKL, Bishop James Doyle of Kildare and Leighlin, in a letter to Daniel O’Connell compared to one of “those mighty convulsions of nature, which spread desolation for a while only to prepare a place for a new exhibition of her powers”.

The Eroica symphony was originally to be dedicated to Napoleon, First Consul, but Beethoven changed his mind, when Napoleon crowned himself Emperor. He likened the first movement of his Fifth Symphony to “fate knocking on the door”. One needs to be in the right mood to listen to Beethoven in that mode. Unfortunately, his choral setting of Schiller’s Ode to Joy in the last movement of the Ninth Symphony, which has become the European anthem, is rarely played alongside national anthems. The EU, despite its importance, does not arouse the same patriotism as the nation.

Beethoven struggled with sacred music, being more of a humanist, as illustrated by his Creatures of Prometheus”

As Swafford acknowledges, in the genre of the string quartet Beethoven certainly equalled Haydn, who remains its locus classicus. Whereas Haydn was devout and attributed his inspiration to above, Beethoven struggled with sacred music, being more of a humanist, as illustrated by his Creatures of Prometheus, intended with his forgotten oratorio Christ on the Mount of Olives to be a response to Haydn’s Creation.

Nor was he able to provide easily settings of the Mass, which formed the summit of Haydn’s achievement. In some Viennese churches, the masses of Mozart, Haydn and Schubert are regularly performed on Sundays. Swafford regards Beethoven’s rarely heard Missa Solemnis as his greatest work.

Beethoven’s complete piano sonatas on disc played by John O’Conor both soothe and elevate the spirit.