Vincent de Paul: The Lazarist Mission and French Catholic Reform

by Alison Forrestal (Oxford University Press, £70)

Clear Vision: the life and legacy of Noel Clear, Social Justice Champion, 1937-2003

by Gerry Jeffers (Veritas, €16.99)

Daire Keogh

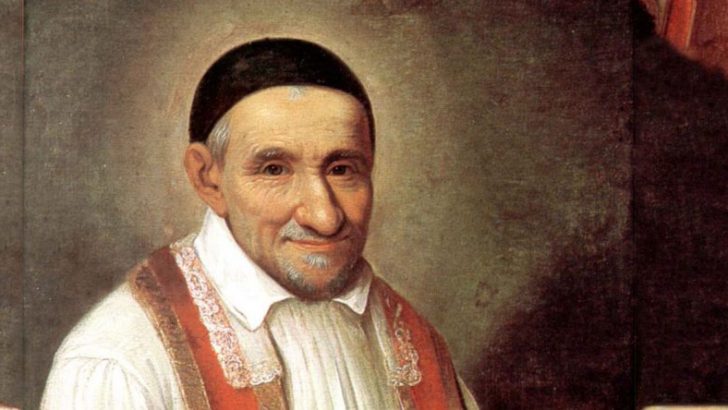

Vincent de Paul (1581-1660) is synonymous with charity and virtue, but, in Ireland his popular acclaim rests largely on the reputation of the society, bearing his name, established in Paris almost two centuries after his death. Both traditions, however come together in recent biographies, the first, a superb assessment of de Paul, and the second, an account of the Vincentian vision modelled in the life of an extraordinary social activist, Noel Clear (1937-2003).

de Paul has had his fair share of biographies. The first, which appeared just four years after his death, set the case for canonisation, and successive volumes, including Pierre Coste’s monumental study (Paris, 1931), were essentially hagiography.

That genre has its limitations, not least of which is the tendency to see their subject as exceptional, unique, or the quintessential ‘lone ranger’. They frequently employ stereotypical tropes, including ambition, captivity and conversion, and seldom do they take cognisance of historical context. de Paul has suffered in this traditional telling, which presents his as a benefice hunter, a ‘Barbary slave’, turned reformer, and the pioneer of France’s religious renaissance.

Forrestal’s magisterial study, in a radical departure from that tradition, captures the dynamism of Vincent and his age, in a fashion which shatters celebrity historian Diarmaid MacCulloch’s facile characterisation of the ‘cheerful and modest’ de Paul.

Instead she examines the saint in his own words, preserved in voluminous archives, and those of his contemporaries, including Jansenist critics who ridiculed his poor theology and humble bragging.

Moreover, the Galway professor’s intimate knowledge of the recent historiography allows her reconstruct the mood of 17th-Century France and the extent to which de Paul’s remarkable legacy rested on his ability to marshal the exceptional energy of the age, and multiple constituencies, nobility, clergy, and pious lay-folk, both men and women including Louise de Marillac, to construct a confident church according to the norms of the Council of Trent (1545-63).

This was never simply an institutional revival, but a profoundly spiritual resurgence in which de Paul and his collaborators sought to construct a vibrant faith community, served by devout priests and, characterised by prayer and the exercise of communal charity. In this context, Forrestal’s chapters on formation are particularly instructive, and illustrate the extent to which the catechesis of the laity and the education of the clergy were prioritised in de Paul’s ambitious mission.

Formation is a dominant theme of Clear Vision, too, an affectionate biography of Noel Clear, whose life was inspired by the example of Vincent de Paul.

No biography of a Christian Brothers’ boy would be complete without allusion to corporal punishment, and at Westland Row, Clear stole a hated ‘leather’ in a protest presented as “a pointer to his inclination to action in the face of injustice”. It was at ‘the Row’, too, however that he honed that moral compass, in a curriculum which not only focussed on Catholic social teaching, but provided ample opportunities for its exercise.

In contrast, Jeffers highlights contemporary obstacles to volunteering, such as appropriate vetting and insurance, but in my view, the erosion of the nexus of family, school and parish, which defined Clear’s youth, is a more significant factor. Indeed, teachers frequently observe that while school exercises provide opportunities for students to engage in church based activities, too frequently parishes are at a loss when approached by youthful volunteers.

For Clear, of course, volunteering was not an option, but an imperative. A disposition of sympathy in the face of poverty or injustice was never sufficient where action was required. Like St Vincent he interpreted the Christian ‘mission’ in the broadest sense, as a call to build the Kingdom.

His life was devoted to this task, whether in his career in the Probation and Welfare Service, the Legion of Mary, the St Vincent’s Boys Club which he founded in Inchicore, or in the Society of St Vincent de Paul, where he served as national president. This period is assessed in successive chapters, which, in themselves, represent a significant contribution to the social history of the state.

There is a symmetry in these two volumes which reflect the origin and endurance of the tradition of practical Christianity articulated by St Vincent. Forrestal’s biography has transformed our understanding of Vincent de Paul, one of the Church’s greatest saints, while Jeffer’s Clear Vision celebrates the life and advocacy of a regular Dubliner, one of our own.

Together, they affirm the imperative of Christian charity and illustrate the importance of communal effort. From a pastoral perspective, however, they highlight something precious which we have lost in the Irish church. And yet perhaps in St Viwncent’s schema we might find a strategy for its recovery.

Daire Keogh is Deputy President of Dublin City University.

St Vincent de Paul

St Vincent de Paul