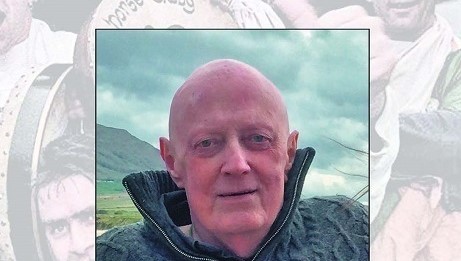

Seán Ryan

‘And Finally…’: A Journalist’s Life in 250 Stories Paddy Murray (Liffey Press, €14.95)

The late Paddy Murray (who died last month) spent 46 years at the coalface of Dublin journalism, producing from a rich vein of Irish life the golden ore of stories which earned him the ‘Young Journalist of the Year’ award in 1975 and ‘Popular Columnist of the Year’ in 2016, so he had plenty of material to draw on for this collection of pieces from the whole length of his career.

Written in a light, very readable style, Paddy’s love of humour, music and sport also figure prominently, alongside plenty of big names he has met and interviewed along the way. In places too there are quite serious pieces. The result is a book which can be heartily recommended.

The product of devout daily Mass-going parents, Tom and Maureen, and with an older brother, Donal, who is a former Bishop of Limerick, it is no surprise that stories of Catholicism pervade the book, which he says was “inspired by the courage of Fr Tony Coote.” Fr Tony’s battle was against motor neuron disease, while Paddy’s was against lymphoma.

Habit

In a very honest account of his life, the author lays bare his habit for ‘messing’ at school and college, with an almost total lack of interest in studying. “By fifth year in Blackrock College, I must have been an utter nightmare,” he confesses. “I disrupted classes. I was always in trouble.

“Seamus Grace was our English teacher, a gentle kind of man. We knew he had spent some years working with the Legion of Mary abroad. A devout man. He loved English – and chess. And he passed on his love for those subjects to his students.

“One day he gave us an essay to be written over the weekend. The title was The Agony of Waiting and I took to the task with gusto, writing about how the Manchester United players behaved as they waited to take to the pitch for the 1968 European Cup final at Wembley. I was liberal with my use of language. I didn’t quite stretch to the ‘f’ word, but I didn’t stop far short.

Essays

“When Mr Grace came into the classroom the day after we had handed up our essays, he threw mine down in front of me and said: ‘Read that out loud.’ I was shocked. I thought this would go beyond suspension and I might be expelled. And there were a few gasps at the colourful language. And utter silence when I finished. And then Mr Grace said: ‘That, gentlemen, is how to write an essay.’

“I was so astonished that, at least in that one class, I changed my behaviour. It started me on the course which saw me get honours in English in the Leaving Cert,” he writes.

Years later it dawned on Paddy that “the essay wasn’t that good at all, but Seamus Grace saw a little rebel, a teenager who was on the verge of destroying his life, and thought that, maybe, a little praise instead of punishment might go a long way.”

A saving grace, surely, which led to Paddy making a successful career from essay-writing. Many of his best are included here, including a sterling defence of his brother, Bishop Donal who, after a particularly nasty campaign by some journalists, resigned following the Murphy Report.

“A good man has been vilified,” he wrote. “A man whose heart is filled with compassion, who has devoted his life to God and to those less fortunate than himself, who has, by his own admission, occasionally failed, has been scapegoated by those who should and do know better.”

He wrote that in the Sunday World, which received hundreds of emails in response. All but three supported Donal.