Matthew Carlson explores the rise and recession of Belfast’s Poor Clares

Nuns are often portrayed in popular media as frail, silent and hidden away from the rest of the world, but the profound story of one religious order in Ireland has flipped that paradigm on its head.

The Poor Clares in Belfast were a group of nuns established in Belfast who served the Down and Connor Diocese from 1924-2012, and their experiences highlight the difficulties they endured in service of their community and Faith in God.

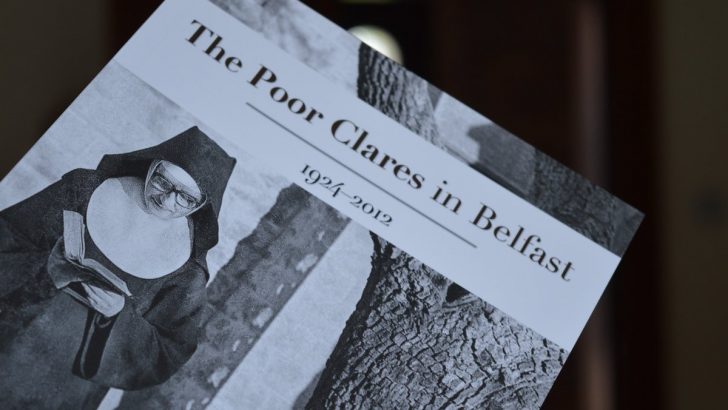

Although their biography was previously unknown, a new book written by Fr Martin Magill of Belfast’s St John’s Parish entitled The Poor Clares in Belfast recounts and collates the moving and powerful stories of the sisters.

Speaking to The Irish Catholic, Fr Martin says his interest in the nuns developed after a friend asked him to find someone who had been impacted by their work. After having trouble in finding someone willing to give a talk on them, Fr Martin took the matter into his own hands.

“I thought I could find someone in the area who knew the Poor Clares pretty well and I could probably get one of them, but actually I couldn’t and I had already agreed to that, so I thought that’s fine so I ended up having to do the research myself,” says Fr Martin. After all his research on the group of nuns, Fr Martin felt the calling to write a book on them so everyone would know their story.

Origins

The Order’s origins go back to the 13th Century with St Clare of Assisi. Clare was born in 1194 as the eldest daughter of an aristocrat family. At the age of 18 in 1212, Clare heard a sermon from Francis, founder of the Franciscan order in 1208, that radically changed her perspective on life.

She decided to leave her family and their wealth in order to live the Gospel more fully.

She cut her hair off and exchanged her extravagant garments for plain ropes and began work in the San Paolo delle Abbadesse. Despite her father’s disapproval, she continued in her Gospel work and moved further away in order to delve deeper into seclusion.

As she continued in her Gospel work, other girls became attracted to the lifestyle and joined her and began living with no money or property, no shoes or meat and lived in a poor house, remaining in silence most of the time. It wasn’t long before they became known as the Poor Ladies of San Damiano.

Even though they spent most of their time in seclusion and lacked material possession, they were known for their high spirits and joy. Clare died in 1253 and 10 years later, the order was named the Order of St Clare or the Poor Clares.

With St Clare as inspiration, the superior of the monastery in Dublin addressed the bishop of the Down and Connor Diocese asking for permission to establish a group of nuns from the order in Belfast in 1923.

Leading up to this point, Belfast had experienced several years of violence and turmoil.

Beginning in late July, 1920 to the end of June, 1922, 491 people were killed during the violence. The last six months of the fighting claimed the lives of 285 people. It is estimated that around 11,000 Catholic people lost their jobs, 23,000 were forced out of their homes and around 500 businesses owned by Catholic people were destroyed.

Seeing the hurt and pain that was being experienced, this drove the nuns of the Poor Clares to set up a headquarters in Belfast in order to be a place of rest and prayer for the people there.

With the permission of the bishop of the Down and Connor Diocese, the sisters officially made the move in May 1924. Quickly the Order began attracting sisters from different areas and the number of nuns in the monastery grew steadily.

In their ministry, the nuns prayed for hours during both night and day for their community. They also listened to the sufferings of the community members. Their lives were lived in solitude, spending much of their time in silence and prayer.

They continued to refuse to own property and only live off of alms given by local people. As money was scarce and impoverished conditions were brought on, the sisters often slept on pallets of straw.

As war began in 1939, the sisters began praying often and fervently for peace, while realising that they were for the most part out of harm’s way.

However, the Belfast Blitz began in April of 1941. German planes bombed several times in the months of April and May with the bombing of April 15 coming dangerously close to the monastery. The bombing lasted five hours and set houses near the monastery on fire.

Mother Colette Egan of the order reported in a letter saying that “God was liberal with his grace” in sparing the monastery from destruction.

After the bombing, a crater was discovered less than a half mile away in the middle of the road. Even though the sisters had been spared of the bombing for the most part, much of Belfast was not so lucky. Hundreds of people perished in the bombings and much of the city’s living areas had been deemed unlivable.

To cap it off, thousands of people fled Belfast, either because their homes had been destroyed or in fear for their life. In the wake of this tragedy and devastation, the Poor Clares returned to Belfast in efforts to be support to the community.

*****

As time went on, the Poor Clares remained in Belfast and in prayer. They also celebrated various festivals and ceremonies honouring different saints and traditions. Beginning on June 11, 1954, the sisters celebrated a ‘Forty Hours’ Devotion’.

The practice references to the Gospel of Matthew Chapter 26, in which Jesus visits the Garden of Gethsemane and encourages his disciples to stay awake and pray. It involves putting a large Eucharistic Host in a receptacle called a monstrance in the centre of the altar. As Catholics believe that Jesus is present in the Host, they are encouraged to pray in the presence of Jesus Christ for a continuous 40 hours. As time went on though, the calmness and somewhat peace was short lived in Belfast.

Riots

In the early months of 1969, loyalist paramilitaries planted several bombs in Northern Ireland, including in Castlereagh in East Belfast. Violent riots began in July of that year. A journal kept by the sisters recorded these riots, but became quiet after the entries of 1969.

The next recorded documentation came in May of 1972, with the sisters describing that riots were continuing in the North. The following July, the bodies of two men, Hugh Clawson and David Fisher, were found by several children playing in the Cliftonville cricket club which was next to the monastery. Events such as this created a traumatising environment in Belfast which became another time of intensive praying for the sisters.

According to Fr Martin, parishioners would often come to Mass every day and the group of people who attended daily formed a special bond with each other as well as with the sisters, a true sense of belonging and family. In this time, the Poor Clares didn’t serve as counsellors in offering ways to cope with these experiences, but rather served as a safe space to talk.

They created a confidential surrounding with a listening ear which became known as their ‘ministry of listening’. “The nuns themselves were providing a ministry that really wasn’t available at the time especially during the Troubles. They provided a safe space where they could listen,” said Fr Martin.

The journal kept by the sisters records that one of the groups of people that they served frequently was the wives of men who had been killed in fighting or in riots. These women were described as often having children who they felt the need to be strong in front of, as someone who was going to make sure they were looked after.

On the inside, they were broken and scared, feeling like they needed to be strong for their children. In these cases, the nuns provided a safe space for these kinds of broken people to find a place of refuge.

One particular family included a mother, father and their two sons. Over the years of the Troubles, the family adopted seven other children. Tragedy struck as one of their birth sons was tortured and killed.

The report says that at first the mother didn’t know what to do, she just sat on the couch and cried all day. Stories such as these were the reason that the Poor Clares were put in Belfast, to help people and to pray for them in their struggles.

This was the way of the sisters. They weren’t intervening on behalf of the people to men, but to God. In times of anxiety or troubles, the nuns prayed and then prayed some more.

In 1993, the sisters began welcoming nuns from the Philippines, but around this time, the number of nuns serving in the monastery began to decline. Over the next few years, it became evident that the number of sisters leaving was greater than the number of sisters that were joining.

*****

In 2012, the remaining five sisters of the Poor Clares in Belfast voted to close down the monastery and have the sisters relocated. The three Filipino sisters returned to the monasteries from which they came and the two Irish sisters were admitted to other groups of Poor Clares in Ireland.

“They were there for 88 years and one of the main things was I didn’t expect to have an emotional reaction to the book. But honestly the Belfast that the sisters left was totally different than the Belfast they arrived in,” said Fr Martin.

“One thing as well is that there are a lot of terrible things that nuns and priests and brothers and lay Catholics get in terms of child abuse for example. And understandably, people get judgmental and condemning of the Church and that’s understandable because it is appalling,” said Fr Martin.

“But they don’t see a lot of the good work that those people do.”

Even though many members of the community felt the loss of the sisters, the nuns encouraged people to continue with them in Faith and prayer.

In less than a century, the Poor Clares endured some of the most difficult ordeals that can be experienced, and their story recounts the rise and recession of a religious order who provided needed help to the people of Belfast.

And they did it with joy and thanksgiving in their hearts.

To purchase the The Poor Clares in Belfast, see: http://shanway.com/product/the-poor-clares-in-belfast/.