Travellers in the Golden Realm: How Mughal India Connected England to the World, by Lubaaba Al-Azami

(John Murray, £25.00 / €30.50 )

This is a most arresting book, though not always for the reasons the author may have hoped for. It was, it seems, originally to be published under a different title First Encounters: How England and Mughal; India Shaped the World. Dr Al-Azami has worked on the intersection of English literature with the Orient in many areas, including Shakespeare.

Near the very start of the book the author describes the act of John Felton who posted up on the door of the bishop of London’s palace the bull excommunicating Queen Elizabeth I, which he had brought from France, and was distributing secretly.

He was arrested and eventually done to death: “England’s Catholic subjects had their first martyr”, the author remarks. But Felton was very far from being England’s first martyr under the Tudors – as indicated by the fact that his act of faith is recorded in the second volume of Bede Camm’s Lives of the English Martyrs. The first volume was devoted to the martyrs under her father Henry VIII.

Disturbs

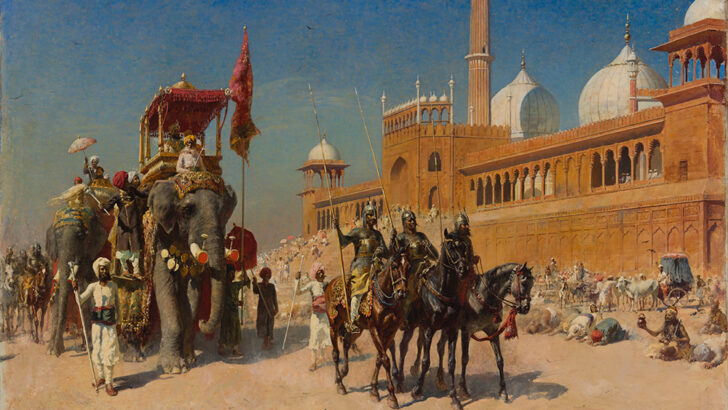

A small point perhaps, but it disturbs one: some history books are made up of small points, others of rapidly moving narratives. This book, a highly coloured account of the glories of Mughal India being its main intention, is one of the latter.

But the persecutions that some Catholics faced in England are not irrelevant to the story the author tells. Her narrative is arranged around her accounts of a series of English men who travelled to India, some for trade, some for knowledge, others to spread the word of the gospels in an Islamic state; state rather than country, for India then as now, was a subcontinent with many varied religions, mostly polytheistic.

The most interesting aspect of his four decades in India was his absorption in Indian culture and poetry – this is of course quite in keeping with Jesuits elsewhere, as in China”

Among her first travellers is Thomas Stephens, who went out on a Portuguese ship to India, later becoming a Jesuit. Avoiding the dangers of living as such under the rule of Queen Elizabeth he naturally preferred India. This was in 1579. The fleet he was on was attacked by English pirates, for in those days the English preyed on the Spanish and Portuguese ships coming from the New World, this was seen at home as patriotism; but by their victims as simple crime: such is the way of the world.

The author remarks on the violence of the Portuguese and Jesuits in striving to gain and sustain converts. Much, it might be said, as the Queen, back in England also used violence to sustain the established Church there.

But by far the most interesting aspect of his four decades in India was his absorption in Indian culture and poetry – this is of course quite in keeping with Jesuits elsewhere, as in China.

He even wrote in an Indian language a long poem about the salvation history of the world called the Kristapuran, which Dr Al-Azami notes is still much admired by Indian litterateurs to this day. An account of India by Stephens was included by Richard Hakluyt in his famous compendium of English explorations in 1589, so laying the groundwork for further English incursions into these realms of gold and scent.

And it is to these later travellers and adventurers that the bulk of her book, with its vivid evocations of the India of the day, is devoted.

Attitude

Yet there remains a curious matter of attitude on the part of the author. Her book is dedicated “To Gaza”, where she explains “Colonial violence continues to burn”, which is fair enough.

But this rightly denounced Colonial violence belongs to the British, the Spanish, the Portuguese, Dutch and French Empires. Other empires whose record for violence is just as brutal, the Arab Conquest itself, the Ottoman Empire, the Central Asian Mughals in their descent upon and conquest of India, all are seen in a more benevolent light. Surely this cannot simply be that she considered the Muslim empires were among the “good things” of history irrespective of the cruelties involved.

The real heirs of Mughal India were indeed the British, when Queen Victoria was raised by her home government in 1877 to the grand title of Empress of India, a realm that had come into existence de facto in 1855. Irish readers will need little guidance to fit these dates into the course of Irish colonial history.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello