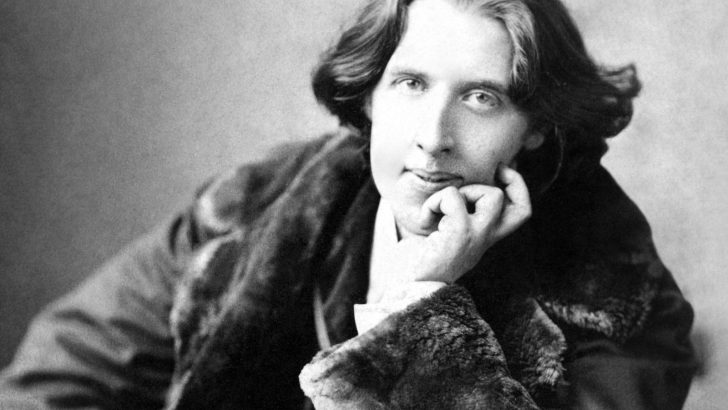

Perhaps few things provoke Irish eye-rolling quite so much as the clichéd tendency of our cousins across the Irish Sea to claim Irish sporting and acting successes as ‘British’, but it was especially bizarre to read last week a catholicherald.co.uk piece claiming Oscar Wilde’s deathbed conversion as an English phenomenon.

In ‘The Passion of Oscar Wilde’, Aaron Taylor begins with the observation that if you “think of the ‘Second Spring’of English Catholicism…you will probably picture converts such as Cardinal Newman, Ronald Knox and GK Chesterton”. Noting that Wilde is not usually ranked with them, he observes that The Happy Prince, a new film about the final years of Wilde’s life, may help to change that.

So begins an article that never mentions how Wilde was Irish rather than English, that names the priest – the Passionist Fr Cuthbert Dunne – who received the dying Wilde into the Church without acknowledging that he too was Irish rather than English, and that omits the salient point that the dying Wilde received the Last Rites in France, rather than in England.

Sins of omission

These are simply the obvious sins of omission in the piece. Anyone with more familiarity with Wilde’s life would have read the piece and wondered at the absence of any references to how his Irish mother, ‘Speranza’ had been attracted to the Catholic Church despite being a Protestant: she wrote an article in 1850 praising its cultural achievements, arranged for both her sons to have an irregular ‘second baptism’ by a Catholic priest in Glencree, Co. Wicklow, and had both the boys taught Catholic theology.

Indeed, when Wilde years later became friends with the Jesuits of Dublin’s Gardiner Street, it seems that his father grew irritated and allegedly encouraged his son’s transfer from Trinity College to Oxford to quell his son’s growing fascination with Catholicism.

If this was indeed Sir William’s objective, it can only be said that his plan was not especially successful, with Wilde considering a public conversion in the following years and him retaining an interest in Catholicism even through the 1880s and 1890s, although even then it should perhaps be noted that the Irish writer only returned to the Church into which he had been baptised in the 1850s when definitively off English soil.

*****

Continuing the theme of cluelessness towards matters Irish, this week’s blogs.spectator.co.uk podcast by Catholic Herald Editor-in-chief Damian Thompson asks ‘Could Dublin’s preachy liberals save Ireland’s abortion ban?’ A discussion between Thompson and an Australian who became an Irish citizen when he was living in Ireland in the 1970s, our editor @MichaelKellyIC described it on Twitter as “the definition of an ‘outsider’ echo chamber view on Ireland lacking any real insight”.

That’s a kind reading of it, really. One to miss

Speaking of podcasts, last month saw me quizzed by the American scholars Matt Bernico and Dean Dettloff who together tweet as @TheMagnificast about the Catholicism and leftish political aspects of the 1916 Rising. Two years on since the publication of The Irish Catholic’s 1916: The Church and the Rising, theologycorner.net/magnificast offered a rare opportunity to discuss how Faith and radical politics intersected in 1916.

Asked what I wish people understood about 1916, the key thing I tried to stress was that an Irish understanding of the Rising needs to grasp the essential Catholicism of the rebellion and the society in which it took place, such that talk of how independent Ireland somehow betrayed the men and women of 1916 finally stops.

British readings of the Rising, I added, would gain immensely by acknowledging that the 1920 partition of Ireland was the fruit not of the Rising and War of Independence but a response to a threat of war from Ulster’s unionists; decided on in principle by London in 1913, it was enabled by a sympathy among Britain’s ruling classes with Ulster Protestants, their mentality “coloured”, as the late Ronan Fanning observed, by flagrant anti-Catholicism.

It’s an hour long, but I hope at least some of you will find it a worthwhile one.

Greg Daly

Greg Daly Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde