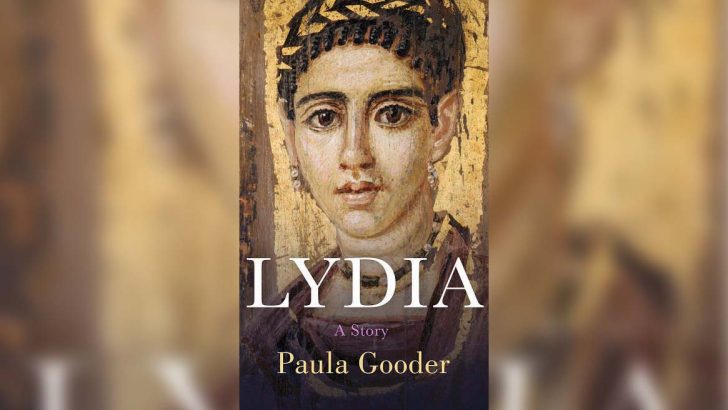

Lydia: A Story by Paula Gooder (Hodder & Stoughton, £16.99 / €19.99)

A couple of weeks ago, over a Saturday lunch, we were discussing with a friend in her large rural garden, the question of those recent novels which mix history and fiction.

The case in point was Colm Tobin’s book on Thomas Mann. I expressed very strongly my reserve about this book, thinking one either writes a novel, or one writes a biography. Mixing the two, I felt, left readers in a sort of limbo of uncertainty about the factual nature of what they reading.

Later in the week, however, I reconsidered. Looking back over the centuries I thought about other novels: Georg Ebers’ An Egyptian Princess (1864), Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur (“the most influential Christian book of the nineteenth century”), Bulwer Lytton’s The Last Days of Pompeii, and Quo Vadis, the masterpiece of the Polish writer Henryk Sienkiewicz. Yes, indeed, historical novels have long had great influence: Walter Scott’s novels virtually invented the idea of modern Scotland.

So perhaps there might be something to be said for this novel after all. Well while not in the same class as the novels mentioned, as the author would admit, it certainly achieves a resonance of its own which has a modern flavour. She says her aim was not to write “a novel”. Novels are stories that exist for their own sake and which are constrained only by the imagination of their author. She wanted to create a context, however, that brings modern scholarship to life by creating a true sense of the Pauline period.

Lydia as a New Testament fire has come to be seen as the “first European” to become a Christian convert: a claim which will arouse the immediate interest of many.

Substance

The author herself is a woman of substance. She is Canon Chancellor of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, and by extension a scholar with a main interest on St Paul’s life and teachings. She wants to arouse in her readers a little of her own enthusiasm for reading the Bible.

The book is in two parts, the actual novel, which fills two thirds of the space, and a long afterword that discuses in great detail of the new scholarship that underlies its narrative line.

It is no reflection on the author’s powers as a novelist to confess that I found the nature of the new discoveries, and debates she vividly describes in part two, more exiting. This may well be a matter of personal taste. I do not deny that. But it makes me feel I should look back again at her first novel, which I decided would not be reviewed here, and give that too another chance. In any case, on the evidence of this book, it would also be well worth reading.

In any case Lydia is like one of those docudramas on television and internet. It carries its own sense of conviction. But readers should not imagine that scholarship is dull. It too has its own dramas and excitements. There is nothing “dry as dust” about modern Biblical investigations.

She rightly reminds her readers that at some time in dealing with her own book, they should reread acts 16:11-40, and the epistle of Paul to the Philippians in which are to be found the basic facts of own interpretation.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello