This week marks the centenary of the murder of a priest who stood up for his flock in the US deep south, writes Chai Brady

One hundred years ago, a series of events led to the remarkable incident of a priest from Co. Roscommon being shot dead by a hardline Protestant minister who was also a member of the racist Ku Klux Klan (KKK).

As America continues to struggle with the legacy of supremacy and racism, it is worth remembering Fr James Coyle’s story: a man who faced prejudice and threats as well as ministered during the height of the Spanish flu pandemic – a situation similar to what the Church faces now due to Covid-19 but arguably more challenging – and still held his resolve.

He was born in Drum in rural Roscommon 1873 just 20 years after the Great Famine in which a million Irish people starved and a further two million left as refugees in search of a better life, mostly in North America.

His childhood was marked by the agitation of the so-called Land War when Catholic peasant farmers campaigned for a fair rent and fixity of tenure on the land they worked.

He was ordained a priest in 1896. At the time there was a shortage of priests in the southern states of the US and an abundance in Ireland, so after Fr Coyle’s ordination in Rome he was dispatched to Alabama, where anti-Catholicism and segregation were rampant.

Birmingham

Fr Coyle served as pastor of the Cathedral of St Paul in Birmingham for almost 17 years. Before that he had ministered for eight years in Mobile. While there he also became a charter member of the Mobile council of the Knights of Columbus – founded by a son of Irish immigrants Fr Michael J. McGivney.

Fr Coyle subsequently became the chaplain for the Birmingham Council 635 of the Knights of Columbus and contemporaries said his passion and fervour for the Faith attracted more people to join the growing Catholic community. At the time, the Catholic population of Birmingham was growing rapidly due to an influx of thousands of Italian miners and steelworkers.

The growing Catholic presence was not universally welcomed. At the time, ‘the Klan’ was the predominant influence in Alabama dubbing itself a ‘patriotic’ fraternity which targeted Catholics, Jews, African Americans and others loosely dubbed as foreigners. This was the second generation of the KKK, said to have been inspired by the notorious silent film Birth of a Nation in 1915. By the mid-1920s, there were four million ‘klansmen’ in the US.

Laws

It was a time when laws were passed that allowed Catholic convents, monasteries and hospitals to be searched without a warrant. The KKK fuelled hysteria that the Knights of St Columbus were the military arm of the Pope and were stockpiling weapons and planning an insurrection.

They also spread hysterical and false claims accusing Catholics of kidnapping Protestant children and women. Fr Coyle was ready to put himself in the firing line to defend the Church and did so until his untimely end.

Edwin Stephenson, who was a minister in the now defunct Methodist Episcopal Church and a proud member of the KKK, had a well-known hatred of Catholics and subsequently of Fr Coyle.

Ruth, his daughter, became fascinated with Catholicism when she was 12-years-old and began secretly taking instruction from the nuns at the Convent of Mercy. She was subsequently baptised a Catholic on April 10, 1921, when she was 18. However, the new convert was beaten badly when her parents discovered what she had done.

Undeterred, just months later on August 11, Ruth Stephenson married the 44-year-old Pedro Gussman, who being from Puerto Rico was Catholic. Mr Gussman had previously worked at the Rev. Stephenson’s house several years earlier.

Fr Coyle had been the celebrant for the nuptial Mass and witnessed the couple exchange their vows. But, shortly after the wedding, enraged by the ceremony and his daughter’s new union Rev. Stephenson went to the Catholic church with his rifle. There he found Fr Coyle reading on the porch of St Paul’s and shot him three times, once in the head. Fr Coyle died very shortly afterwards.

Murder

Rev. Stephenson immediately turned himself in, and was charged with murder. He was defended by a lawyer called Hugo Black, who later became a klansman himself. The legal fees were paid for by the KKK, Rev. Stephenson was found not guilty and Mr Black went on to represent the Democratic party in the US Senate and subsequently served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court until his death just 50 years ago in 1971.

On the centenary of his murder, Fr Coyle is still remembered with pride in his native Co. Roscommon – particularly by his family. Speaking to The Irish Catholic, Fr Coyle’s grandniece Chrissy Killian who lives a few miles outside Drum explained how her great-aunt Marcella Coyle – Fr Coyle’s sister – lived with her after returning to Ireland from Alabama. In the US, she had helped out in the parish where Fr Coyle met his untimely end.

“She was there when the incident happened. My aunt was a witness at the wedding. Uncle Jim [Fr Coyle] told her to witness from the sacristy for her safety.

“She was in the rectory when [Rev.] Stephenson walked up and shot uncle Jim. She went out and she screamed and called for a doctor,” Ms Killian recalled to The Irish Catholic.

Fr Coyle’s sister – Marcella – continued to live in Alabama, but moved to Mobile after the murder before returning to Ireland in 1963 where she lived out her final days with Ms Killian and her family.

“I would have cared for her for about ten years before I went to college…and was bedridden and she would constantly speak about her brother.

“He was very much part of the family,” Ms Killian recalls.

She recalls Fr Coyle being spoken of as “a very poetic man, a strong-minded and principled man – a strong Fenian [Irish nationalist] back in the early 1900s.

“I’ve read a lot of his poetry that he wrote about Ireland and Ireland’s struggles through 1916 [the Easter Rising] and the early 1920s. When [Éamon] de Valera went over to the United States to gain support for the Irish Republic he went down to Birmingham, Alabama to visit Uncle Jim and I’ve seen photographs of the two together,” she recalls.

Progressive

By the standards of the day, Fr Coyle was also remarkably progressive according to Ms Killian. “He allowed black people into his church, and I think he founded the first black school in Birmingham which was very badly received by the Ku Klux Klan. He was honoured by the civil rights movement in Birmingham, Alabama and they have a library dedicated in his honour and a website.

“They remember him everywhere in Alabama,” she says with pride.

Speaking about Fr Coyle’s funeral Mass, Ms Killian said “it was massive and all the bishops attended”.

There is an extensive report on the funeral in the Catholic Monthly of September, 1921, Volume 12 by a Mrs L.T. Beecher. It states there were “thousands of men and women of all classes and denominations gathered around St Paul’s church long before the hour of three o’clock, which has been fixed for the funeral service…”

The glowing report on Fr Cloyle begins: “During the past month the members of St Paul’s parish and, indeed, all the Catholics of the district, have been so stricken with grief, have received such a test of their Christian patience and fortitude as, pray God, may come no more to us personally or collectively while this earthly trial lasts. Deep in the hearts of all who revere simple goodness and loyalty to an ideal was our priest who for seventeen years went about among us doing good.”

Bishop Edward P. Allen, who was the Bishop of Mobile from 1853-1926 and a son if Irish immigrants from Co. Meath, further attested to Fr Coyle’s character and good works after his death saying: “Fr Coyle was a zealous and devoted missionary and afterwards a successful professor and rector of McGill Institute, one to whom the students could look up and whose wise direction they could follow. I felt that he would make a worthy successor of the late Fr O’Reilly. In this, I have not been disappointed.

“He laboured and preached the word of God in season and out of season, visiting the sick, instructing the little ones of the poor and needy and afflicted. He especially laboured to bring the people to the holy sacrifice of the Mass, the unbloody sacrifice of Calvary which was offered first by our Divine Lord at the Last Supper.”

The report also states that the funeral sermon was preached by another Irish cleric Fr Michael Henry of Mobile who had known Fr Coyle as a child and they had gone to Rome and studied in college together before being ordained at the same time. They both became missionaries and arrived in the US on the same boat and worked in Mobile together too.

Fr Henry said: “The Catholic Church will say to those who persecute it and its priests of even Jesus Christ himself said, Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do. That is the kind of people we Catholics are. We believe in law and order and the institutions of the land which upholds these.

“Today, dear brethren, there is sorrow in your heart, and tears in your eyes. Dry your tears, for they are not necessary. We honour him, and the bishop honoured him, and the priests were his devoted friends. The people of St Paul have never failed to respond to any call…if Fr Coyle were here today he would say, ‘Hold fast to the faith and carry on the work.’ “And I make this appeal to you for the sake of the sacrifice he made for you that you carry on the work. I appeal to the children, to those who are grown up, to the old men and women, to those he loved so much, to pray for his soul. It was a great and noble soul,” Fr Henry said.

Home

Ms Killian said that Fr Coyle came home regularly, and during the earlier part of the 1900s up until his death. “He would have taken a lot of family photographs at the time. He was a larger-than-life character. He went to a Jesuit school, he was very strongly principled in his Catholic beliefs and his principles for humanity and equality of people and freedom for people and I think that was very central to his philosophy on life because it was evident in his sermons and in his poetry.

She added: “He is a very good example for good Christian living and living by your faith. He obviously came from a very learned and principled family and those values carry forward into the rest of his life and if you come from a rural area in south Roscommon there’s nothing to say that you can’t make a difference in the world and he certainly did in his short years,” she says.

Ms Killian adds that her uncle, who was a nephew of Fr Coyle, went on to become a priest for his native Diocese of Elphin. Inspired by his heroic uncle, Fr Dennis Killian went out to Alabama and ministered there for ten years after his ordination as a tribute to the murdered priest.

Something Bigger

Ms Killian’s sister, Sheila Killian has written a novel entitled ‘Something Bigger’ which chronicles the story from their aunt, Marcella’s point of view.

For Anton Lennon, the manager of the Drum Heritage Centre in Roscommon – where Fr Coyle was from – there is an enduring need to remember the heroic priest and his little-known story.

“He was a great man for people’s rights, he stood with the people,” Mr Lennon told The Irish Catholic, adding that the priest used to write home decrying the what he had read about the “suffering of people at the hands of the Black and Tans and the heavy-handed approach by the British authorities [in Ireland] at the time”.

“We are always keen to keep the memory of Fr James Coyle alive, we have a display here at the centre all the time on Fr Coyle’s life and his early days in Drum.

“In the late 1980s Drum Heritage Group restored Drum old cemetery. Fr Coyle’s parents’ grave, Eoin and Margaret (Durney) Coyle, is located in Drum old cemetery. Both of them were teachers, Eoin was schoolmaster in Drumpark National School which is now the local parish hall and his wife Margaret was a teacher at nearby Cornafulla National School.”

He added the heritage group are “proud of our association with the late Fr Coyle and keeping his story alive”.

During the Spanish flu, a pandemic in which it is estimated 50 million people died, places of worship in Alabama were closed to stop the spread of the virus – much like what happened in many jurisdictions due to the current pandemic.

Fr Coyle reached out to his parishioners at this time to emphasise the importance of the congregation coming together for Mass. He said: “You are for the first time in your lives, deprived of hearing Mass on Sunday, and you will, I trust, from this very circumstance appreciate more thoroughly what the Mass is for Catholics…Sunday Mass is no mere gathering for prayer, no coming to a temple to join in hymns to the maker, or to listen to the words of a spiritual guide, pointing out he means whereby men may walk in righteousness and go forward on the narrow way that leads to life eternal.

Contemplation

“No, there is something else that draws the Catholics, to the wonderment of non-Catholics, from their warm homes on cold bleak winter dawns to trample through snow-covered streets in their thousands and hundreds of thousands to a crowded church, where they kneel reverently absorbed in the contemplation of a man, who in a strange garb, at a lighted altar, genuflects and bows and performs strange actions and speaks in a long dead tongue. What draws the multitude?

The Mass, the unutterable sweetness of the Mass.”

Fr Coyle’s voice and his heroic witness echoes from the past, and while his sacrifice surely inspires so too perhaps his devotion to the Mass and his closeness to people deprived of it as Irish Catholics have indeed endured during this current pandemic. His message still stands the test of time and is perhaps more relevant than ever.

Chai Brady

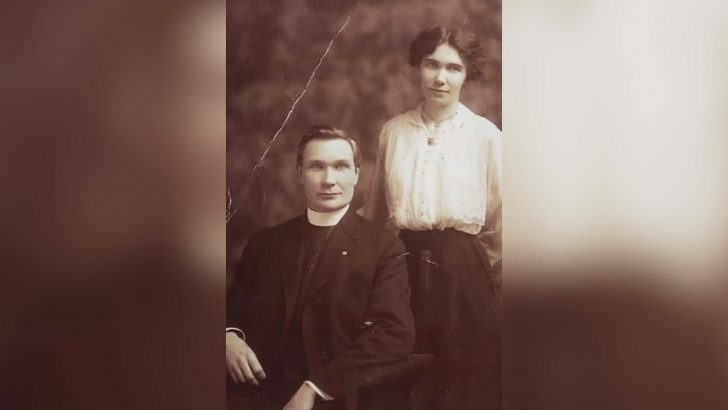

Chai Brady Fr James Coyle and his sister Marcella.

Fr James Coyle and his sister Marcella.