“He started to draw himself as a ‘saint’. He was seeing himself in a different world,” hears Renata Milán Morales.

A short documentary was premiered at the end of this year, In God’s Hands. Originally from Roscommon, Niall Sheerin, director of the film explains to The Irish Catholic the meaning of it. In God’s Hands is dedicated to Niall’s late brother Michael, who was a recognised tattoo artist who died in 2022 at the age of 42 from pulmonary hypertension.

Michael was a tattoo artist who worked all over the world from Dublin to Helsinki, Holland, Germany and Los Angeles. He was diagnosed with sarcoidosis in 2020, but his health worsened, turning over time to a branch of pulmonary hypertension.

Michael’s life was an example of creativity, resilience, and faith. As an artist, brother, and deep thinker, he left behind a body of work that inspires those who knew him. Michael’s story is an example of the power of faith and the nature of art.

Expression

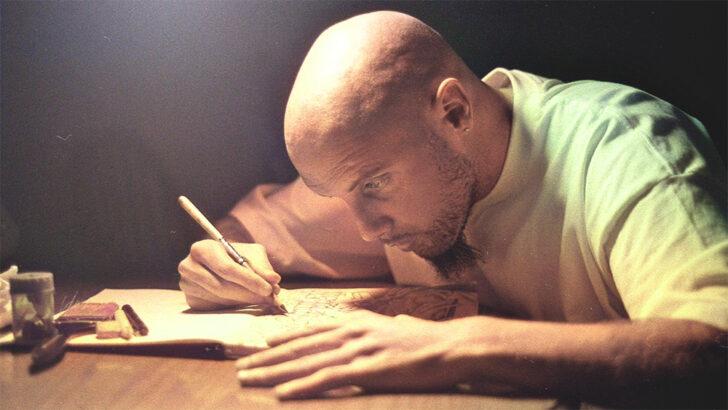

The tattoo artist and illustrator’s journey evolved over the years. As his health declined, his art grew more reflective, touching on ideas such of mortality, eternity, and faith. “Michael used art to express his inner thoughts and emotions as he was getting sicker. I found that interesting – that his art changed as well. It became deeper, more profound. And it was interesting looking at that after he died as well,” his brother Niall explained.

The film director’s purpose behind his work was not only a tribute to his brother’s life, but also an exploration of his spiritual and artistic evolution. He told this paper that “the main goal [of the documentary] is putting something out there in the world to commemorate Michael. I have a lot of video footage from Michael’s phone, and from documentaries that would have been made on Michael in the past as well. But [I] also [have] a lot of artworks. I decided to make a short documentary based around those portraits… As well [as how] Michael used art as well. Michael used art to express his inner thoughts and emotions as he was getting sicker.”

He had faith that he was in safe hands, even as he grew increasingly ill, and that brings myself and my family a lot of comfort”

The title comes from a drawing Michael did a couple of weeks before he died. “He was in the cafeteria in Galway University Hospital, probably drinking a coffee. He loved coffee! But the drawing is interesting in that it has the face of Jesus in the froth of the coffee cup. It has written in the sugar sachets ‘HOPE’ and ‘FAITH’ and the cup is being held by his own hand,” described Niall Sheerin.

Michael’s brother continued, “written around it is ‘IN GODS HANDS’… He had faith that he was in safe hands, even as he grew increasingly ill, and that brings myself and my family a lot of comfort. Nobody realised Michael was dying but maybe he sensed it himself.”

“The function of all art lies in fact in breaking through the narrow and tortuous enclosure of the finite, in which man is immerged while living here below, and in providing a window to the infinite for his hungry soul,” shared In 1952 Pope Pius XII on an address to a group of Italian artists on the sixth Roman Quadrennia. Michael’s later works, featuring angels, saints, and depictions of the afterlife displayed his preoccupation with eternal life.

Faith

Though Michael was not a conventional churchgoer, his faith was strong. It shaped his worldview and his art. “Faith gave him immense comfort… As he grew older, he became fascinated by religious art -angels, saints, the afterlife. During his illness, he found solace in drawing these images, which reflected his strong belief that he was going somewhere better,” his brother told this paper.

In Catholic tradition, suffering is not a just a struggle but a way to participate in Christ’s redemptive work. Michael’s art became a way for processing his pain and finding peace during his illness. His representations of divine figures symbolised hope, grace, and the presence of God, even in moments of darkness.

Michael’s spiritual journey was “personal,” yet his faith was evident in his art, his conversations, and his approach to life”

“He started to draw himself as a saint. He was seeing himself in a different world which wasn’t apparent when he was alive. It’s only when you look at it now and you think, ‘he was looking at himself from a from a different point of view. I suppose that was maybe him coming to terms with his illness. Coming to terms of his own mortality,” shared his brother.

Michael’s spiritual journey was “personal,” yet his faith was evident in his art, his conversations, and his approach to life. One of the most important moments in his journey came during a trip to Canada, which his brother describes as “a kind of religious awakening.”

Michael’s faith found its voice in his art, his fascination with religious imagery. “Michael was always very interested in Renaissance art… which is a lot about afterlife and angels and religious iconography. He used to love going to museums and cathedrals. When he got sick, which I found interesting, he was obsessed with drawing angels and Saints,” expressed Niall Sheerin. From Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel to the stained-glass windows of churches, Catholic art has been a bridge between the human and divine.

“Michael’s art is still alive in the world. On walls, on skin, and in people’s lives. That’s the blessing of it all. His work carries his essence forward, giving comfort not just to our family but to everyone touched by his creativity,” his brother shared.

Inspiration

As we move from Christmas Day into the New Year – a time of reflection and of new beginnings – Michael’s story reminds us of the importance of faith, creativity, and gratitude in our lives. His philosophy of life was, “life is yours to live. He taught me to be positive, and to believe in something.”

Niall Sheerin, Michael’s brother and film director finds inspiration in his art and his approach to life. His legacy reminds us that even in the face of adversity, it is possible to find beauty, express hope, and leave an impact on the world.

“I found that interesting that his art changed as he went over the course of life. After getting sick, I suppose, it became deeper, more profound. It was interesting looking at that after he died. That is kind of the essence of what this documentary is – an exploration of his art.”

Since his passing, I’ve felt his presence. In a strange way, he’s never left. It’s as though he knew he’d die, and he drew himself as a saint, as if he knew his place in our lives after he was gone”

Renata Milán Morales

Renata Milán Morales Michael Sheerin

Michael Sheerin