The World of Books by the Books Editor

In recent years a new sort of library movement has got under way across Europe, which promises well, because it is created and run by ordinary people and depends on neither commerce nor the state to function.

This is the little library movement. I first came across it in, of all places, the booking hall of Belfast Central Station, on a trip to the North.

It consisted simply of a set of shelves set up against the wall filled with a random selection of books of all kinds, all donated.

The idea is the readers will donate a book and take away another, thus sharing their books with others, while also enjoying other people’s ideas of what constitutes a good read.

The movement began, so I understand, in Austria. The idea soon spread through Switzerland and elsewhere and now I suppose in various forms can be found everywhere.

We have all seen in both pubs and coffee shops such little colonies of books. They provide customers with some relaxation for their short time out from the worries of work or life.

The idea, however, has spread way beyond the city and its fashionable whims, into small towns and rural villages. The little libraries can be found anywhere there is some free space, protected from the weather and perhaps from vandals, can be found.

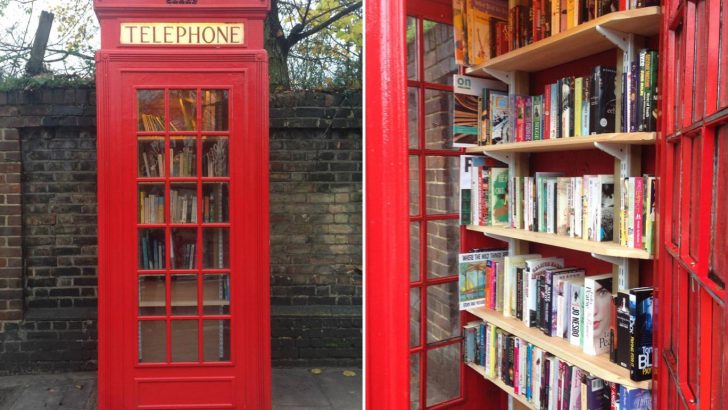

Some have even been set up in out-of-service telephones boxes – ideal places one would have thought: carelessly abandoned by feckless privatisation, they have been taken over by the community. All too often when people talk of “community action” they mean either the local authority, or radical groups of right or left with an agenda. Those who love and want to encourage the reading of books have an agenda too, to spread the love of literature in all its forms, with all its insights into life, history, and the prospect for the future.

In the 1950s, Victorian-style high-minded libraries still survived. Their committees ensured that they were worthy. They stocked, for instance, many books and manuals needed by those studying for their City and Guilds in the past. There were books on philosophy, culture, and the literary classics, as well as book-keeping, plumbing and woodwork.

But these libraries were not widely used by the upper or middle classes. Most patronised the subscription circulation libraries, for which there were many, run on the original model of Mudie’s Library in London.

These ranged from a set of shelves in a local corner shop from which you could borrow a current novels too much grander one such as the London Times Subscription Library which was in Brown Thomas’s in Dublin’s Grafton Street. In the early 1960s that closed with a great sell-off, destroyed by the advent of the paperback. By that time the corner shop libraries were gone too.

As a result the public libraries, now that they had to be used by the respectable, and not merely by the deprived, were greatly improved. But now, as most librarians agree, they have gone into decline as regards level of stock and choice of books. They are over filled with ephemeral literary fiction – there are long delays on non-fiction books, as fewer are now bought.

Movement

Given the state of the public libraries it is to be hoped that the little corner library movement will spread – like an infectious disease perhaps – across the country.

These will provide every small palce with its own outlet for books, quite independent of book stores with their now over priced-books, or the public library with their cutback budgets. They will provide a new kind of social focus for a small place, cost-free, where the virtues of friendly exchanges of all kinds can be promoted.

“Educate that you may be free” was the once widely known call of Thomas Davis. He was concerned not just with national, but individual freedom. “Read a book a week that you may stay free” ought to be the slogan of modern communities. Depend on yourselves, dear readers, for commerce, cultural organisations, and the state are not the full solution to the problem, the readers themselves are.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello