“Awareness of technological innovation and change can make us alert to cultural and social change”, writes Mary Kenny

It is well known that the greatest political changes often occur through ‘events’, rather than through the carefully-laid plans and projects of politicians.

And perhaps the biggest changes to our social and cultural lives often occur through technology. Charles Dickens set Oliver Twist in the 1830s when poor little boys (and girls) were sent up chimneys as chimney-sweeps – a horribly cruel practice. Christians campaigned to stop this, but what made a real difference was the invention of a chimney-brush which could do the job instead.

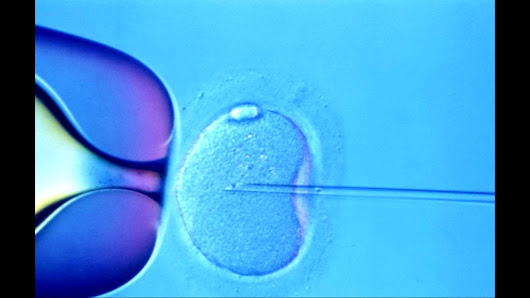

Awareness of technological innovation and change can make us alert to cultural and social change. And one of the extraordinary innovations happening right now is the development of the artificial womb.

Photographs

Just recently, photographs were released showing a successful experiment on unborn lambs, who were brought forward to gestational age in a newly-developed ‘biobag’. This replaces the uterus, and is much more sophisticated than the current incubator, (currently employed for premature babies).

This is a radical innovation which, the biological scientists say, will very soon make ‘ectogenesis’ possible.

‘Ectogenesis’ is a word coined by the scientist J.B.S. Haldene in 1924 – meaning foetal development outside the womb, or via an artificial womb.

Transplants of the uterus are already taking place: 10 women in Britain have been approved by the medical authorities to proceed with a pregnancy through a donated uterus.

The artificial womb and the donated uterus have huge implications for the future of life sciences. These developments could save the lives of very premature babies – who are surviving, now, from 22 weeks’ pregnancy, but need a high degree of medical support – and transform the debate, too, on abortion. “Artificial wombs, able to gestate a foetus outside the body, will completely upend feminism’s arguments on bodily autonomy,” writes Eleanor Robertson in The Guardian.

Ectogenesis is also being hailed as “a gift to gay men, transwomen and many other groups whose longing for children is circumscribed to varying extents”.

It is an extraordinary development and should be on the agenda for anyone concerned with bio-ethics.

Abortion rarely needed to save mother

I am slightly puzzled by the statement made by Dr Chris Fitzpatrick’s in The Irish Times, saying that: “Having worked as a consultant for over 20 years in Ireland, I have direct experience of terminating pregnancies in order to save the life of the mother.”

From a purely obstetric point of view, I would like to be told more about what the circumstances involved. When I was researching a book about abortion in London, I was told by a gynaecologist and obstetrician, Dr David Painter, who I watched carry out social abortions, that it was very unusual today to have to terminate a pregnancy to save the life of the mother. “If the woman wants the child, we can nearly always bring her through,” he told me.

I don’t question Dr Fitzpatrick’s evident sincerity, but we do need, I think, more clinical information about the medical circumstances he refers to. I had been led to believe, by other medical consultants, that this operation is now very unlikely indeed – thankfully, too.

Lay-led liturgies genuinely communal

That Limerick should have had a recent ‘day without a Mass’, three evening ones aside, because priests were on an in-service day was greeted with dismay, and understandably so. But I’ve recently attended prayer events conducted by the laity and they often have a warm spiritual feeling and generate a true sense of community. In our seaside town in Kent, there have been a series of Stations of the Resurrection, entirely lay-led and they’ve been lovely.

This is, of course, not at all the same as the Mass, whose position is unique. But I do think something special happens when the community gets together to in a prayer, not priest-led, but genuinely communal. It strikes me that the experiences of the early Christians must have been very like this, and there is a sense of extraordinary continuity in that feeling.

Expect the unexpected

Yes, events can surprise: after nearly a century of campaigning for a united Ireland through patriotic rhetoric, historical claims on geography, and sometimes, through violence – who would have predicted that the prospect would suddenly look realistic following on a British referendum rebellion against Brussels’ rule? Prepare for the unexpected!

Mary Kenny

Mary Kenny