Even though I didn’t experience it, early 1990s Ireland seemed to a time of great cultural and behavioural flux. Poring over documents in the archives I got an unmistakable sense that this was one of the most defining periods in Ireland in terms of the island’s widespread disavowal of life through a Christian lens and the outset of its gradual but firm shift to secular norms.

I do also think that for all of the worrisome trends that started to intensify during this period, it was a time where we matured as a people, who in turn matured to the world and its unsightly realities that command attention.

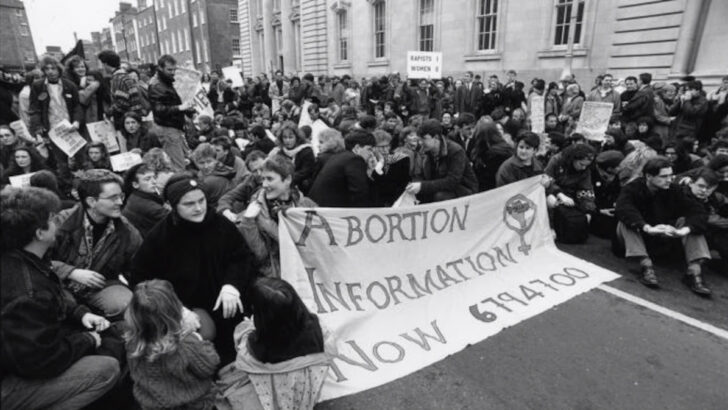

The X Case, a seminal judgment issued by the Supreme Court in 1992 which established the right of Irish women to an abortion if a pregnant woman’s life was at risk because of pregnancy, including the risk of suicide, was borne out of a harrowing situation where a fourteen-year-old girl had been the victim of a statutory rape by a neighbour and became pregnant. After an injunction was granted by the High Court preventing the girl from procuring an abortion in another jurisdiction, she became suicidal.

Reflect

The case and the resulting media commentary gripped the nation and prompted many to reflect on the country’s existing laws around abortion access, and the Vatican was not shy in expressing its misgivings about a referendum that took place later in the year. It proposed to allow women and girls to get information and to leave Ireland to access abortion care in other countries. According to a leading Vatican official, the complexities of the rederendum were so sensitive that “people of ordinary intelligence would not understand the implications”.

The “ordinary intelligence” comments were made by then-Archbishop Jean-Louis Tauran, Secretary for Relations with States of the Secretariat of State and a future cardinal.

These details were outlined in a letter sent by the Irish Ambassador to the Holy See Gearóid Ó Broin to secretary general in the Department of the Taoiseach Padraig O hUiginn, who after meeting with Archbishop Tauran said in the letter that “the Holy See was very upset about the forthcoming referenda in Ireland” and that “apparently the Pope told him (Archbishop Tauran) at their last meeting of his worries on the matter”.

Ambassador Ó Broin concluded that Archbishop Tauran ‘seemed to be registering a general distaste with the whole subject and fear that the idea of abortion as a right was making some progress in Ireland’”

Archbishop Tauran thought that “people were not being given a real choice since to vote no would leave the situation as it is, with abortion permissible in some circumstances and to vote yes would recognise a right to abortion” and that “the complexities are such that he thought people of ordinary intelligence would not understand all the implications”.

Although fairly strident in his views, Archbishop Tauran conceded to the “likelihood that the amendments would pass”, but one of the overwhelming factors for this view was because the referendum and general election were being held on the same day and this “could colour people’s views on a complex moral issue”.

Ambassador Ó Broin concluded that Archbishop Tauran “seemed to be registering a general distaste with the whole subject and fear that the idea of abortion as a right was making some progress in Ireland”.

Dismissed

All of this may well be dismissed as relatively unassuming insights about the inner feelings of the Vatican at one of the most consequential periods in Ireland’s modern history but there is a tenuous connection that emerged in the fullness of time and it involved a lot of the year 2018.

Archbishop Tauran had the momentous honour of announcing Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio as Pope in 2013. The next time a pope visited Ireland was in 2018 and the person who paid the visit was Cardinal Bergoglio, who had taken the name of Francis.

Pope Francis’ visit to the country, only the second pope to visit Ireland, came just three months after Ireland’s citizens had voted to legalise abortion. The visionary in all of this, Archbishop Tauran, who would’ve been vindicated in his 1992 judgment that “abortion as a right was making some sort of progress in Ireland”, wasn’t alive at this point. He had died just over a month before the Pope’s visit in July 2018 at 75.

Everything is relative if you search for long enough, I suppose.

Brandon Scott

Brandon Scott The demonstration against the High Court injunction forbidding a 14-year-old alleged rape victim from obtaining an abortion in Britain reaches Government Buildings. Photograph: Eric Luke/The Irish Times

The demonstration against the High Court injunction forbidding a 14-year-old alleged rape victim from obtaining an abortion in Britain reaches Government Buildings. Photograph: Eric Luke/The Irish Times