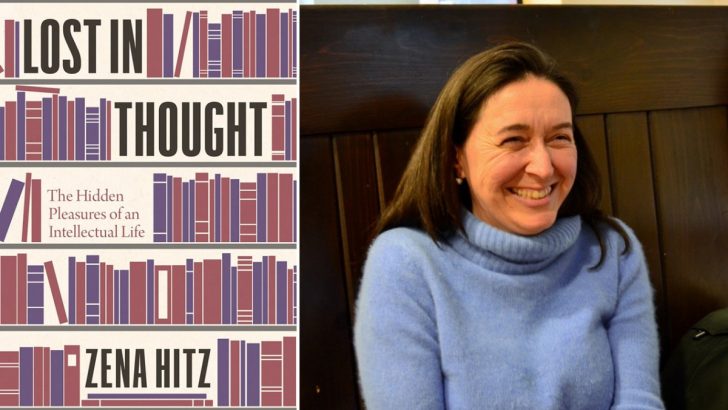

Lost in Thought. The Hidden Pleasures of Intellectual Life

by Zena Hitz (Princeton University Press, £18.99)

Frank Litton

The world is too much with us. The most distinctive feature of Irish culture is its contempt for all things intellectual. Consider the questions that occupy us in the daily round. Because we are social animals, we seek to fit in, meeting the expectations of our fellows.

So we ask what is required of us in this or that circumstance. Because we, well most of us, must earn a living, we ask how we can secure, or increase our income, win promotion, or find a better job, a more profitable enterprise.

Because we seek love and understanding, we are prompted to evaluate our lives, to find purpose and meaning.

This is not a hierarchy of questions. It would be a strange life, indeed, in which all three did not figure. The attention given to each, of course, varies, from individual to individual, from one time to another, and in different cultures.

Our culture pays scant attention, and affords little value, to the life of the mind. Inevitable, perhaps, in an impoverished rural society, with few markets for its agricultural surplus. But in a modern, urban, society?

Anti-intellectualism is not unique to Ireland. Nor are we the only society where it is advancing, or deepening.

Zina Hitz reports how, in the US, the intrinsic value of studying the humanities has been displaced. Students are ‘consumers’ and universities scramble to sell them ‘products’ that promise to further their interests in making money.

So she writes, not a defence of the life of the mind, nor a lament for its eclipse, but far more positively, in its praise. She reminds us of the “hidden pleasures of the intellectual life”.

Account

Her account is persuasive, not least because it is personal. She writes of her own experience as an academic – she holds a PhD in ancient philosophy from Princeton. Her enthusiasm for philosophy drained away as social pressures and academic competition took centre stage.

She joined a convent of contemplative nuns for a time and discovered that the intellectual life remained her vocation. She recounts how she regained her sense of the good of that life. That journey informs her reading of the journeys of others.

We are less pluralist and more intolerant of views that question the reigning orthodoxy”

We read of Primo Levi, the novels of Elena Ferrante, Augustine, John of the Cross, Simone Weil, Dorothy Day. Their journeys exemplify how social pressures, ambition and the search for the true and the good interact. We may think, or our culture may allow us think that only the first two count. The journeys show us that this is not so. The intellectual life is its own reward that is discovered in the interaction.

Hitz is not concerned with the spiritual life. While this has affinities with the intellectual life and while some of her examples were on a spiritual quest, her topic is our natural urge to follow Socrates in living out his assertion that the unexamined life is not worth living. The affinity is worth exploring.

Many years ago Basil Chubb, professor of politics, TCD, told us that Irish political culture was “localist, authoritarian and anti-intellectual”. It was generally accepted that the dominating influence of the Catholic Church was largely responsible for the last two attributes.

How do things stand today? Despite the growth in numbers attending university, we are more anti-intellectual than ever.

We are less pluralist and more intolerant of views that question the reigning orthodoxy which suggests that our authoritarian score, is, if anything, higher.

The influence of the Catholic Church approaches the vanishing point. Perhaps we got it wrong.

As transcendence is disparaged, the motive to examine our lives, never strong, diminishes.

Getting and spending is all there is.

Hitz does not discuss the rise of anti-intellectualism. This is not a criticism, it is not the subject of her book. But it is a book that should be written, indeed, that needs to be written.