Irish Parliamentarians: deputies and senators, 1918-2018

by Anthony White (Institute of Public Administration, €60.00)

Felix M. Larkin

It is axiomatic that we get the politicians we deserve. We elect them, so we have nobody to blame but ourselves. However, while our politicians generally get a bad press, we in Ireland have been reasonably well served by them. Most have been dedicated public servants, with the national interest at heart.

This volume is a biographical dictionary of those politicians who reached the upper echelons, the TDs and senators. It spans the period from the 1918 general election and the subsequent meeting of the First Dáil up to and including the current Dáil and Seanad. The current Dáil is the 32nd.

The dictionary is a remarkable compilation, with pithy biographical information about each TD and senator. There have been 1,302 deputies and 478 senators, with 318 TDs also serving terms as senators.

All of them are here: the good, the bad and the ugly – the ugly being the venal and the corrupt, as distinct from those who were just not very good at the job. The account doesn’t pull its punches about those who fell foul of the law and/or tribunals of enquiry, but is otherwise non-judgmental. It sticks to the facts.

It is circumspect about those with a background in subversive activity. As Prof. Vincent Comerford has noted elsewhere, “there scarcely has been…a Dáil Éireann that did not include members who, at some stage, had dabbled in Irish rebellion”. It is one of the great strengths of the Irish parliament that it has been able to accommodate such people and, in many cases, tame them.

This volume lead us to the question: who was the greatest of our politicians since 1918? Most people would probably say Seán Lemass because of his role in the modernisation of the Irish economy.

In my view, however, that accolade belongs to Donogh O’Malley on account of his introduction of the ‘free’ secondary education scheme in 1967. This effected the greatest social advance in Ireland since Wyndham’s Land Act of 1903, which facilitated the transfer of land ownership from the landlords to their tenants – and there has been no comparable achievement since 1967.

The well-educated workforce produced by the O’Malley scheme – shall we call them “O’Malley’s children”? – was at least as important in the economic development of Ireland as IDA grants and generous tax breaks for business.

Moreover, those who could not find employment in Ireland in recent times emigrated with skills that previous generations lacked. This enabled them to avoid the degradation of life as navvies or domestic servants in foreign lands, the fate of so many earlier Irish emigrants.

Enthusiasts

All political enthusiasts, and many more besides, would enjoy browsing in this volume – and it will be an important source book for scholars. Its author, Dr Tony White, has also written a very valuable complementary article in the current edition of Studies (Winter 2018/19), in which he makes some broad observations based on his detailed research for this dictionary.

Perhaps the most surprising of these observations is his conclusion that the evidence for political dynasties in the Dáil and Seanad is not compelling, despite a popular perception that there is a strong dynastic element in Irish politics.

A final point: Dr White’s dictionary is now supplemented by an entirely unrelated project just launched by the Oireachtas Library which provides online access to a bibliography of published material on the Dáil and Seanad – books, journal articles, video and other sources. It is freely available at www.oireachtas.ie/bibliography

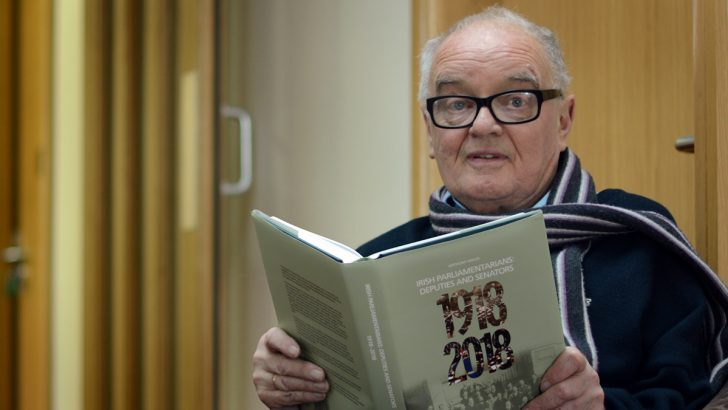

Anthony White with his new book

Anthony White with his new book