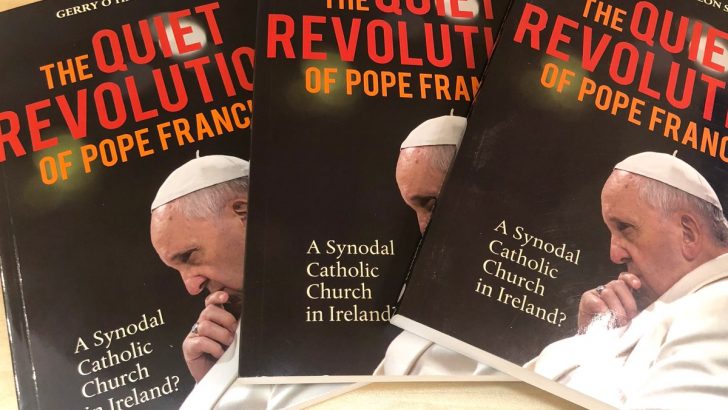

The Quiet Revolution of Pope Francis: A Synodal Catholic Church in Ireland?

by Gerry O’Hanlon SJ (Messenger Publications, €12.95)

Peter Hegarty

“It is through the clash of ideas in public debate that truth emerges,” Gerry O’Hanlon observes in a favourable overview of the reforms undertaken and envisaged by Pope Francis.

He writes of the slow emergence of what he calls a “synodal” Church, a decentralised, less hierarchical organisation that listens, to Catholics, to people of other faiths, to people of none. What Francis is doing has ‘ecumenical implications.’ By listening the Church will earn the right to be heard. Like any organisation it must attend to the “signs of the times” if it wants to move with the times. The signs of our times include suspicion of authority and hierarchies.

Discussion

Francis is encouraging discussions and setting in train processes which may, or may not, lead somewhere. He has, for instance, encouraged the discussion of priestly celibacy at a coming synod in the Amazon.

He is preparing to transfer power and authority to national and regional episcopal conferences, to strengthen the presence of women in the Church, and to allow “the voice of the faithful” to be heard at all levels.

O’Hanlon, a theologian, is impressively familiar with Church history. He writes of the “diversity of structures” in the early Church. Francis looks backward to that time when debate thrived and women held positions of authority.

Over the centuries the Church became hierarchical, and the popes monarchical. Rome was suspicious of science, at odds with Enlightenment thinking and revolutionary politics. During what one theologian called “the long 19th Century” – it lasted almost 160 years – the Church even decided that in some circumstances the pope was infallible. It prized docility and unquestioning obedience.

In the middle of the last century the Church began moving closer to a world it had kept at arm’s length for centuries. The Bible, it decided, was not literally true. The Second Vatican Council emphasised dialogue, “persuasion rather than declaration”.

The Church discussed reform, but often did not effect it: “There was insufficient structural, legal and institutional grounding of many of the changes envisaged, in particular those concerning a more collegial Church at all levels.”

Francis has set about grounding those changes.

He is in a similar position to Mikhail Gorbachev when he began his shake-up of the Soviet Union: he cannot know whether or not his reforms will work, but he can be sure that they will encounter criticism. O’Hanlon does not worry too much about vocal conservative scholars since the Pope welcomes and encourages debate.

Those who will attempt to frustrate reform will work quietly. Many in the Curia “find change difficult and are accustomed to a clericalism which supports ambitious self-seekers”.

Some powerful people are more at ease with ‘a gospel of prosperity.’

Some social conservatives will suspect that the move to synodality “is a cover for changes in Church teaching with regard to gender and sexuality”.

In the United States, there is a robust network of Catholic universities, colleges and lobbies “that consider a traditionalist outlook on faith essential to the moral health of the United States”.

Reform of the Church will likely be a drawn-out process given the strength of the forces ranged against it, but a renewed institution may in time regain relevance and moral authority.