Every March since 1991 has been designated Irish-American Heritage Month in the United States. President Biden has continued the practice again this year, and a proclamation to this effect was signed by him on February 29th.

America has not always been so sympathetic towards Irish immigrants and their descendants, as this book illustrates. Written by Dan Milner, an American historian and musicologist, it was first issued in 2019. A paperback edition has been published for a wider readership.

Integration

The theme of the book is “the changing fortunes of New York’s Irish Catholics” between 1783 – the date of the Treaty of Paris, ending the American Revolution – and 1883 when the first term of New York’s first Irish Catholic mayor, WR Grace, comes to an end.

As explained in the introduction, it is the story of how the Catholic Irish gradually integrated within the city, rather than assimilated. In order to assimilate, they would have had to adopt the mainstream Anglo-Protestant culture.

Instead, as Milner writes, “the same virile strain within the Hibernian psyche that had overwhelmingly rejected the abandonment of Gaelic Catholic being in Ireland continued to hold forth in Manhattan”.

The Irish in New York in the years of this study suffered “discrimination, intimidation and physical hostility”. They are overwhelmingly poor, lower working class and living in tenements.

Their real significance lies perhaps in their place in the evolution of the folk music tradition”

Their story is told in this book not just as a conventional historical narrative – based on documentary evidence – but also through the medium of popular songs. Milner claims that such songs “are important because they articulate issues and voice points of view from a street-level perspective” and so they “make the act of integration vivid and its steps more discernible”.

They add colour – though, in fairness, little substance – to the story of the Irish in New York. Their real significance lies perhaps in their place in the evolution of the folk music tradition.

A milestone in the progress of the New York Irish towards integration – what Milner calls their “road to respectability” – was the participation of the 69th New York State Militia in the American Civil War. A regiment of the Irish Brigade under Thomas Francis Meagher, it comprised almost entirely Irish Catholics.

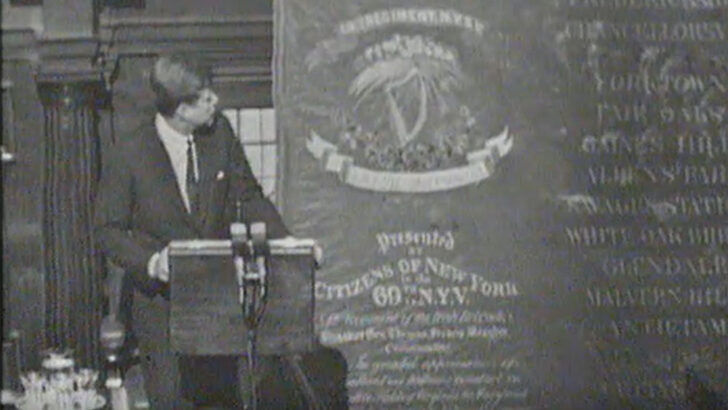

The valour of the ‘Fighting 69th’ in the early battles of the Civil War is the stuff of legend, but their casualties were enormous. Many readers will recall that President Kennedy referred to their feats in his address to the Dáil and Seanad in June 1963, and he presented one of the regiment’s battle flags from the Civil War to the people of Ireland.

Slavery

Curiously, Milner argues that the commitment of the New York Irish to the cause of the Union in the Civil War waned after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. They were prepared to fight for the Union, but not for the abolition of slavery.

They feared that freed slaves would compete for their unskilled jobs and that wage levels would fall as freed slaves joined the workforce. There are, however, obvious parallels between the struggles for integration of the Irish and Black communities in the United States, including that both communities are rich in popular songs.

As quoted by Milner, Harper’s Weekly noted in 1889 that “they are the two races who care the most for song and dance”.

The commitment of the New York Irish to the cause of the Union in the Civil War waned after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863”

President Kennedy speaking to the Dáil and Seanad presents the Irish people with the banner of the Fighting 69th.

President Kennedy speaking to the Dáil and Seanad presents the Irish people with the banner of the Fighting 69th.