Anthony Gaughan

A Poet in the House: Patrick Kavanagh at Priory Grove, by Elizabeth O’Toole (Lilliput Press, €15.00/£13.00)

Elizabeth O’Toole’s memoir is a fascinating snapshot of Patrick Kavanagh in his later years, in very different circumstances than people often imagined him in.

Kavanagh was born near Inniskeen, Co. Monaghan, on October 23 1904. After attending the local national school he assisted his father in a shoe-repairing business and a small farm.

A rhymer from his earliest years, three of his poems were published in the Irish Statesman in 1925 and thereafter his poems began to appear in English journals. From 1931 onwards he was a frequent visitor to Dublin where he became known in literary circles as the ‘farmer poet’.

After a brief spell in London Kavanagh returned to Dublin in 1939 and contributed to The Bell, which was edited by Seán Ó Faoláin, with Frank O’Connor as the poetry editor. He eked out a precarious existence as a freelance journalist writing features and book reviews for the three daily newspapers. He also contributed a gossip column in the Irish Press and book reviews and reports for The Standard.

Kavanagh became established as a character-about-town, tall, shabbily-dressed, wearing a battered hat and thick horn-rimmed glasses, walking like a ploughman and with a pronounced Monaghan accent. While enjoying this notoriety, he resented intrusive familiarity and cultivated a gruff rudeness to ward off unwanted company.

In the magazine Kavanagh’s Weekly (April 12 to July 5 1952), which he wrote with his brother Peter (who paid the printer), he irritated and alienated so many influential persons and institutions that after its closure he was virtually unemployable in Ireland. His life hit rock bottom between the spring of 1954 and that of 1955 when he was involved in a high-court libel action against The Leader – his foolish attempt to win at the libel game. Then by March 1955 he was suffering from lung cancer.

Owing to the poor recompense he received for his literary work and a ‘serious drink problem’ his life in Dublin became more and more precarious. Numerous well-wishers assisted him. Among them was Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, who visited him, sent him generous remittances by courier.

With the help of Michael Tierney, President of UCD, the Archbishop ensured that he was hired by the College as an extramural lecturer. However, he had no friends in the English Department. But there were friends in the Bohemian world such as John Ryan and Envoy, and also on The Irish Farmers Journal where he had a column for years, that now receives little attention from critics. But in this book we have something very different: a contented poet in a domestic situation, where the poet’s many human qualities shine through.

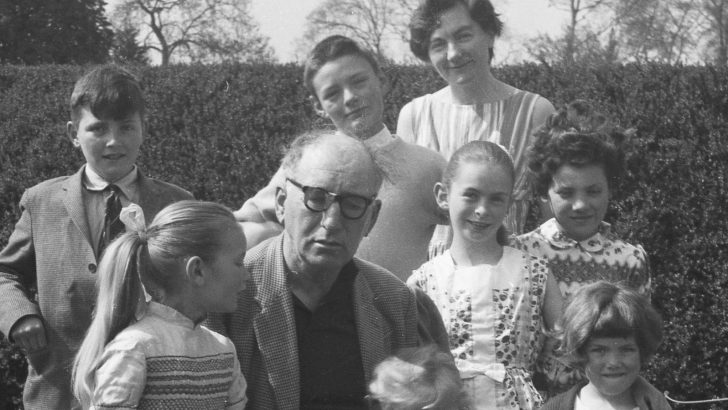

No one was more generous to Kavanagh at that time than the O’Toole family in the Dublin suburb at Stillorgan, where he was a house guest for six months in the spring and winter of 1961.

This is how Elizabeth O’Toole describes how he arrived for his sojourn with the family: “It was a winter night after Christmas. There had been a relentless downpour of sleet and rain all day. It was bitterly cold, chilling to the bone. Hearing our car, I ran out to welcome my husband, Jimmy. In the half-dark I nearly fell over a sack on the doorstep. I bent down to pick it up. It was soaking wet, and it wasn’t a sack at all. It was Patrick Kavanagh.”

The O’Tooles treated Kavanagh as one of their own. He was given facilities to exercise his skill as a cobbler, to compose his poetry, to engage in his other literary pursuits and to attend to his correspondence. He developed a bond between himself and the four O’Toole children and enthusiastically joined in all the family outings.

The result, vouched for by Elizabeth O’Toole, was a genial, happy and relaxed Patrick Kavanagh far from his popular profile as an angry, embittered curmudgeon. One of Elizabeth’s other abiding memories of her close association with Kavanagh was the poet’s conviction about the presence of God in everything.

In an Afterward Brian Lynch adds a useful corrective overview of Elizabeth O’Toole’s memoir and that of her daughter, Margot. In so doing he also provides a gossipy account of the bohemian life-style of the Dublin literati of the 1950s and 1960s.

Leading poets

When he died on November 30 1967, Patrick Kavanagh left a corpus of literary work which marked him out to have been one of the leading poets in the Ireland of his time.

Only now is the deeply religious nature of his poetry receiving full recognition, revealing him to have been a sort of saint, if a saint in a battered hat.

Pic. Poet Patrick Kavanagh in the garden of Priory Grove, Stillorgan, probably in the spring of 1961, surrounded by the love - and respect - of the O’Toole family. Photo shows Elizabeth O’Toole (back right), with some of her family. From the private collection of Elizabeth O’Toole.

Pic. Poet Patrick Kavanagh in the garden of Priory Grove, Stillorgan, probably in the spring of 1961, surrounded by the love - and respect - of the O’Toole family. Photo shows Elizabeth O’Toole (back right), with some of her family. From the private collection of Elizabeth O’Toole.