A Bloody Night: The Irish at Rorke’s Drift

by Dan Harvey (Merrion Press, €14.99)

A Bloody Day: The Irish at Waterloo

by Dan Harvey (Merrion Press, €14.99)

J. Anthony Gaughan

These are interesting accounts by the same author of two very different battles, but which had one thing in common – the participation of Irish soldiers.

Rorke’s Drift is located on the border between Natal and Zululand in South Africa – ‘drift’ is the Boer word for a ford. Here in 1849 two buildings were erected by Irishman Jim Rorke, a hunter, trader and farmer.

Later on the buildings were used by Otto Witt, a Swedish missionary. When the British army invaded Zululand in 1879 they established Rorke’s Drift as a forward operational base with stores of food, military supplies and a small garrison to protect it.

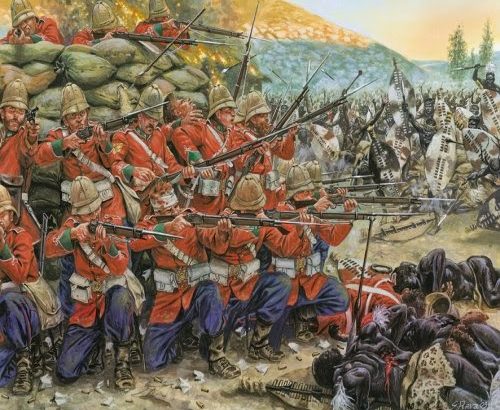

Soon after the British army entered Zulu territory it was surrounded by a huge army of Zulu warriors and suffered a catastrophic defeat at Isandlwana with the loss of 1,300 officers and men. Elated by their victory the Zulus next set about wiping out the garrison at nearby Rorke’s Drift.

Carnage

The garrison, realising that their only chance of surviving was to successfully defend the base, fortified a small square, which incorporated the two buildings in the area. During a night of carnage, with superior firepower – rifles against assegais and animal-hide shields – and exceptional courage they manged to fend off tens of thousands of Zulu warriors. It was the stuff of Thermopylae and became a legend in the British army. The defenders were subsequently the recipients of VC’s and other medals for bravery. It became in time a celebrated film by Cy Enderfield, much repeated on TV, and became the centre of a mini tourist business in its own right, which celebrated both the British soldiers and the Zulu warriors.

Dan Harvey lists and in some cases profiles the Irish-born, those born of Irish parents in Britain and those with Irish names and connections who distinguished themselves at Rorke’s Drift. He notes that all the eye-witness accounts and the official report singled out James Langley Dalton, who was born in London to Irish parents, as having played the key-role in ensuring a successful outcome to the ‘bloody night’.

The village of Waterloo in Belgium is famous as the site of one of the most significant battles in European, if not world history. Here on 18 June 1815 on one side was the Grand Army of Napoleon, on the other the armies of Britain, Belgium, Holland and Prussia under the command of the Duke of Wellington. The British army comprised one third of the allied army and 40% of its soldiers were Irish.

The battle was a long day of appalling savagery and butchery. Harvey provides a blow for blow account of it as it swayed to and fro. His account is not for the faint-hearted.

Austrian, British, French, German and Russian historians all have their own take on the battle.

But two facts are clear. Wellington won the day because of his defensive talents and tactics, his troops’ tenacity, Field Marshal Gebhard von Blücher’s arrival with his Prussian forces and indeed some of Napoleon’s own tactical mistakes. The battle brought a definite conclusion to the struggle against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France.

Harvey profiles a number of the Irish who fought in the battle of Waterloo. Among those was Maurice Shea from Co. Kerry. He was credited as being the last serving British veteran of the battle of Waterloo, dying in March 1892 at the age of 97.

Then there was the Duke of Wellington who, allegedly when reminded that he was Irish because of his birth, replied that one could be born in a stable and not be a horse. The author urges his compatriots to take pride in the Irish involvement at Waterloo.

However, it should be remembered that the main reason for the large numbers of Irish in the British army in the 18th Century (Wellington called them “the scum of the earth”) was the same as that for the disproportionate number of Afro-Americans who have fought and died in the US army’s foreign wars during the last 70 years: an escape from poverty and social exclusion.

Rorke's Drift

Rorke's Drift