Spectral Mansions: The Making of a Dublin Tenement, 1800-1914, by Timothy Murtagh

(Four Courts Press for Dublin City Council with aid from the Heritage Council, €30.00/ £26.00)

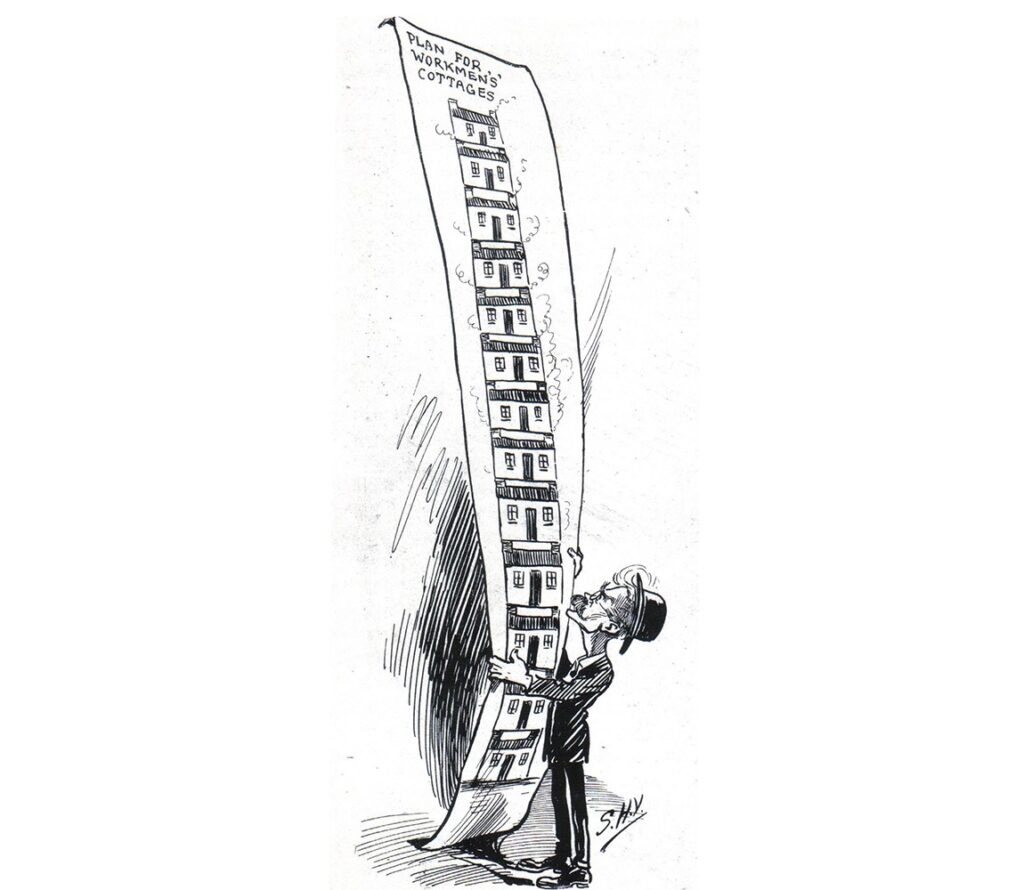

To those familiar only with the ever-rebuilding Dublin of today, there is in this book a strangely prophetic cartoon from a Dublin comic paper of July 1914, captioned ‘Town Planning (Latest Scheme)’. It shows a city expert explaining his latest plan: “Certainly abolish the tenements. Each family a cottage. Suburbs being too far for workers, central ground rent too dear, there being no charge for sky space, the higher the air the purer, we’ll build the cottages on top of each other.”

It shows a 13 story “high-rise”, composed of cottages, such as indeed we now have all over the inner city, some only built the other day. Yet poverty still stalks the city, what with the tented poor, the newly homeless, the refugees without a place.

This book explains much about how we got where we are for good or bad. Timothy Murtagh, a TCD graduate, was an historical consultant to the 14 Henrietta Street Museum and is now a research fellow with the Virtual Treasury of Ireland.

Slum

When I first saw his title, there came into my mind a drawing from The Capuchin Annual in its great days in the 1940s: in a slum house, clearly meant to be in Mountjoy Square or Henrietta Street, a small girl sitting up in its iron framed-bed observing with awe the ghosts of two Georgian dancers, modern squalor haunted by Georgian graciousness. It poses the question Murtagh wants to answer: how are they connected? He tells, in vivid and exact detail, of the consequences of changes to a city, deserted by an elite who had ruthlessly exploited it, early and late.

As a result these pages themselves are indeed a rich treasury of images and maps from the 18th Century down to 1981, many in full colour. Many of the maps, on which various degrees of inner city desperation and squalor are marked on in colour washes, show all this amazing revealing detail. Here for once the visual documents are treated not as decorations, but as a real part of the evidence, by someone who is fully aware of their meaning.

Do not let the dates in the title which conclude in 1914, lead the reader to think that all this horror was well into the Imperial past. A full seventh of the text is devoted to the period after British rule, with all its vagaries of approach to poverty and housing.

Also this too is the old Dublin, the Dublin moated by the two canals. But since 1930 the city has also owned the former townships of Rathmines and Drumcondra. Those were always thought of as the reservations of the prosperous, they also had their pockets of poverty and neglect. Murtagh does indeed discuss these places, but they are not obviously his main brief.

Shades

The book will remind readers of all shades of opinion that poverty “hasn’t gone away, you know”. There are other kinds of poverty too, mental, spiritual and even social, that we cannot expect ‘the authorities’ to mend. Others have been inspired to act though. Murtagh gives a good account of the literary reactions from Joyce and others down to James Plunkett. One fact that stands out is the courage and resilience of Dubliners in adversity.

Over all he has explored the multifarious sources with great thoroughness. One feels this book ought to find future place in every school library. As many people are beginning to lose any sense of what history really can give us, his book will show them.

Henrietta Street, once the abode of the city’s elite, is I suspect only known by those of us who have business with the King’s Inns and the Deeds Office in the little park at the top of it. After this it will have many more, a sort of urban counterpart to the EPIC exhibition down on Custom House Quay what was suffered here in the past. Both need to be seen.

(Latest Scheme)’, The

Lepracaun July 1914.

Peter Costello

Peter Costello ‘A tenement nocturne’ from The

Capuchin Annual 1940.

‘A tenement nocturne’ from The

Capuchin Annual 1940.