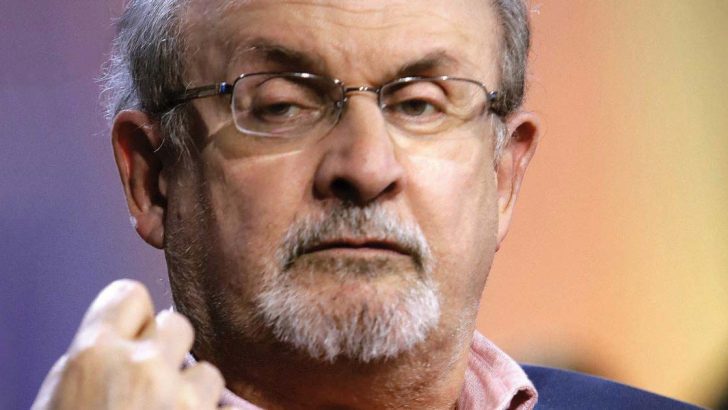

The recent attack on Salman Rushdie, like the massacre of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in 2015, raises fundamental questions about the limits of free speech. There are no easy answers.

Those of us who live in liberal democracies are predictably appalled by the very idea of restrictions, formal or otherwise, on our freedom of speech. Nevertheless how do we react when the target is something sacred within our own culture?

For example, were we in Ireland not aghast about the proposal by Channel 4 to develop a comedy series about the Great Famine? The project was eventually abandoned because of the adverse reaction to it.

And what about the impossibility of satirising the obligatory wearing of the poppy on the BBC in November each year – a point made by the distinguished British theologian, Tina Beattie, in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo massacre?

Remember

We should also remember the outcry when the Monty Python film Life of Brian was released in 1979. We need to be careful not to be hypocritically one-sided in our defence of free speech.

So, are there any limits to freedom of speech? Most of us would agree that nobody is entitled to knowingly speak an untruth or to use abusive language. Nor do we have a right to articulate naked prejudice, to present material or images that are irredeemably racist or xenophobic, anti-Semitic or anti-Islamic, sexist or homophobic. It is wrong to target individuals for what they are, as distinct from what they do.

There is a world of difference between these two approaches. Both may give offence, but whereas the first is gratuitously offensive and hateful, the second is aimed at making people think and question their actions, values and received orthodoxies – and that is an entirely valid pursuit.

As the great American jurist, Oliver Wendell Holmes, once observed, “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market”.

Of course, it is important not to overestimate the extent of the offence that may result from the exercise of freedom of speech – or to be too sympathetic to the allegedly offended. There are, undoubtedly, some people who make it their business to take offence at the slightest thing – in other words, professional offendees.

It is not necessary to take account of them: they are just a nuisance. As for the few who may be genuinely offended – those, in other words, who cannot bring themselves to entertain an idea that is foreign to them – it is open to them simply to disregard the offending item. Nobody is forcing them to read it; they are free to exercise their right to ignore it. Offence is thus very easily avoided.

Offence

In reality, however, much of so-called “offence” is contrived – and calls to suppress the offending material not actually about avoiding offence, but rather about control. Those who exercise control over others – political, religious, economic or otherwise – wish (understandably) to retain it and if possible expand it, and will try to exclude anything and everything that might undermine their authority and the value system, beliefs and thought processes upon which their authority rests.

Protestations of offence are all too often just a cover for denying those they subjugate, or wish to subjugate, the intellectual means to challenge them. It is an insidious manifestation of tyranny, and should be resisted.

Salman Rushdie in defiant mood.

Salman Rushdie in defiant mood.