This Sunday the whole world, it seems, will for a few hours become Irish, or at least recover enough of their nominal ‘Irishness’ to join in the fun.

President Biden, in the name of the American people, will accept yet again a giant bowl of flourishing shamrock, and avow his Irish roots.

Streets around the world will be filled with parades, with begowned boy bishops with crooked mitres, with raucous leprechauns wearing green tops hats and bushy red beards.

But in all the craic and laughter, something important will be overlooked, something very important: St Patrick himself.

This is really strange, for St Patrick is unique among Irish saints of early times: he has actually told us about himself in his own words in a direct and vivid manner.

Consider for a moment the Three Patrons of Ireland, St Patrick, St Columba and St Brigid. What do we know about them and how do we know it?

For St Brigid we have a set of traditional lives in both Irish and Latin. These are about the lady already becoming a figure of legend, even myth.

For St Columba we have an informative life by Adomnán, a near contemporary, who had access to oral sources now lost. It is the man himself at a remove so to speak, but already becoming a pious legend. (Adomnán of Iona’s Life of St Columba is in print in an accessible scholarly edition from Penguin Classics, £8.99.)

By sharp contrast we have two documents attributed to St Patrick himself, his Confession and The Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus. The second is a plea to a Scottish band who had kidnapped some Irish Christians, whom he wanted returned, a document filled with outrage and a passion for justice and religion.

However, the Confession is his own personal account of his life, his own justification of his actions before man and God.

Unique

This is unique. It gives the actual sound, tone, and tenor of a passionate man who has dedicated his life to God’s mission to the Irish.

In the annals of Irish hagiography there is nothing like it. But this unique voice that we hear from Patrick is not, ironically enough, an Irish voice. It is the voice of a Latin speaking Roman, not in the sense of a ‘Roman Catholic’, but in the sense of St Paul in Acts (22:28): a freeborn Christian citizen of the pax Romana.

But Patrick left his childhood home, perhaps somewhere in Somerset, and his family to go into wild and savage Ireland, where the people did not even use money.

My advice is to hear the man himself first, and then move on to see what those attempting to elucidate him have to say”

But to encounter St Patrick readers might be best advice to read a straightforward edition of the plain text – a new edition appeared last month, can be bought from Amazon, and there are many others. In this way if read first without commentary readers will encounter the man himself in all his complexity.

Naturally, as with many other books, this will leave much unfathomed. But my advice is to hear the man himself first, and then move on to see what those attempting to elucidate him have to say.

Dr Healy, the archbishop of Tuam, had a good dictum worth following. In 1905 he published a biography of St Patrick in which he proposed a test for the materials in the traditional lives of the saint: do they conform to the man whose character is revealed in the Confession. If not, he said, they were apocryphal.

Of this second class of books, the most recent and perhaps most interesting, is that by the Columban father Aidan J. Larkin, The Spiritual Journey of St Patrick (Messenger Publications, €14.99). His approach is to elucidate the references in St Patrick, to delve into his own reflected view of himself in the context of his time. This is an enlightened procedure, making this perhaps the most valuable recent book on St Patrick.

It is when one might turn to those writers that attempted to explore the political, social and topographical information in the Irish lives in Latin and Irish that the figure of St Patrick becomes more confused and controversial.

Controversy

It is hard to write a book about St Patrick without arousing controversy, as instanced by David N. Dumville’s St Patrick (Boydell and Brewer, £26.99), which shifted the narrative to the later traditional date of death of 493 – not the date they taught us school, as people say.

Then there is Dr Roy Flechner of UCD, who in his book St Patrick Retold (Princeton University Press, £22.00), casts Patrick in the role, not of a slave, but a slave trader, marketing his father’s stock of slaves at home to Irish buyers.

History often does not provide ‘simple truth’ of any kind, and certainly not about St Patrick”

But what some, perhaps many readers, want is ‘the simple truth’. Well, history often does not provide ‘simple truth’ of any kind, and certainly not about St Patrick.

If readers wish to begin trying to come to terms with the man, who, whatever way you rebrand him, has had an immense influence on Irish ideas about themselves and their country, the first step must be to read his own account of his life and then to try to understand the spiritual basis for his beliefs.

But to come to terms with what annalists, scholars and modern academics, not to speak of manipulative rulers and clergy over the centuries, have made of him is a very different day’s work.

Peter Costello

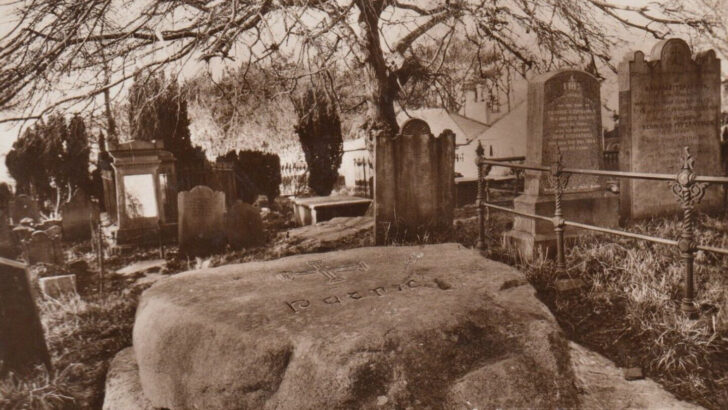

Peter Costello The traditional grave of St Patrick in Downpatrick graveyard, Co. Down

The traditional grave of St Patrick in Downpatrick graveyard, Co. Down